New Tibetan cinema

What comes to mind when you think of Tibet? Plateaus and shepherds? Or an isolated and unchanging lifestyle?

Old Dog, a film by Tibetan director Pema Tseden, which won the best film award at the 15th Brooklyn Film Festival (BFF, dedicated to award independent films from different countries), depicts authentic Tibetan culture in a changing society, shattering many traditional views outsiders have about the region.

Premiering in 2011, the film has thus far won eight awards at international film festivals, including last year's Tokyo FILMeX International Film Festival and Hong Kong International Film Festival.

"I hope the film [reflects] the dignity of people in my hometown, and sustains the local tradition and culture," said director Pema Tseden.

Dog days

Shot in a Tibetan region in China's western Qinghai Province, Old Dog tells a story of a Tibetan family and their old dog, a Tibetan Mastiff. It takes place in a village during the 1990s, when dog thefts were frequent. Gonpo, the leading character, plans on selling the dog to city dwellers.

But Gonpo's father, Akhu, insists on retrieving and buying back the dog, after his son sells the dog.

This conflict between father and son brings other tensions to the surface: for example, the father worries that Gonpo and his wife Rikso, despite being married for three years, have not had a child yet.

The story is humorous yet tragic. At the end of the film, the father chooses a peaceful way to end the life of his old dog instead of selling it, leaving audiences to contemplate the strains the outside material world causes on life in Tibet.

"Although the story is fictional, the dignity is real and heavy," said Dukar Tserang, sound designer of Old Dog.

The director depicts the real side of Tibetan people's life and their deepest thoughts. Coupled with natural scenery like high mountains, blue skies and pastures, the whole film is very poetic, Tserang told the Global Times.

Though it's not a documentary, the film functions to record losses and conflicts Tibetan people face in a materialistic society, said cultural critic Lou Xiaoyuan. The dog represents the dignity of sheep farmers, and by depicting the changes in people's thinking, the film stands as a metaphor for a bigger picture: how to protect Tibetan culture in an increasingly complicated world.

Realistic lens

Pema Tseden's film often reflects the humanistic side of Tibetan culture. Dubbed as the "first generation" of China's Tibetan directors, Tseden has established fame for himself via his previous works on Tibet, The Silent Holy Stones (2005) and The Search (2007).

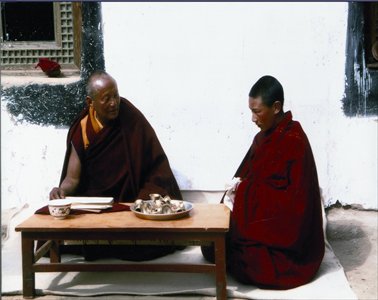

The Silent Holy Stones tells the story of a Lama father-and-son pair living in Tibet, reflecting on the imperceptible influence modern culture brings to their local lifestyles. After the film premiered, audiences abroad and home were interested in the new images of Lama presented in the film.

"Most people's impression about Lama are serious," said Tseden. They might be surprised when they watch the movie, but this is their real life. Monks or Lamas living in temples have feelings like ordinary people. He said that Tibet, like the name of the film, always appears silent and constant, but is in fact changing everyday under the impact of outside culture.

Unlike non-native directors who may focus on certain groups or use symbols to define Tibet, Pema Tseden shows Tibet through the details of everyday life.

"Many people's knowledge about Tibet is from the 1980s," said Tseden, and this is due to misleading films and literature. The Silent Holy Stones is not what many people expected. "I hope people can see a real Tibet in my film," he added.

Heavy use of scenes shot from a distance and fresh actors are also distinctive characteristics of his film.

"Filming from far away parallels Tibetan's aesthetic," said Tseden. "Like Thang-ga (a unique style of painting found in Tibet, originating from Tang Dynasty (618-907)), the whole story can be told clearly in a picture."

These shots from a distant tell audiences the true story and leaves actors room to show their life but also leaves limited room for directors to impose their thoughts.

Through plain depiction of Tibetan's life, this film is more powerful than those that try to symbolize or sensationalize Tibet, said Dukar Tserang.

Ethnic minority films

In the past, many directors have shown interest in Tibet as a subject. Popular Tibetan films by foreign directors include The Salt Men of Tibet (1997) by German director Ulrike Koch and Himalaya (1999) by French director Eric Vall.

Domestic Tibetan films include Serfs (1963) directed by Li Jun, The Horse Thief (1985) by Tian Zhuangzhuang, the Red River Valley (1996) by Feng Xiaoning, and Mountain Patrol (2004) by Lu Chuan, to name a few. These films all attempt to depict Tibet from different angles and time periods.

"Good Tibetan films have something in common," said culture critic Yang Huiqin. "It's their focus on humans. This is illuminating for the production of other ethnic minority films, she said. Different traditions among ethnicities in China result in complicated filming efforts. Exploring people's inner feeling creates sympathy among audiences.

Many of the films reflecting ethnic minority's culture are superficial, said Pema Tseden.

"To go deeper, we need to tell personal stories," he said.