Uncertain future

If you can't remember the last time you've flipped through a literary magazine, you're among the ranks of most Chinese people. Engulfed by convenient methods of obtaining information - from cellphones to tablets - some have bid farewell to magazines. It's no surprise that magazines are fighting for their survival.

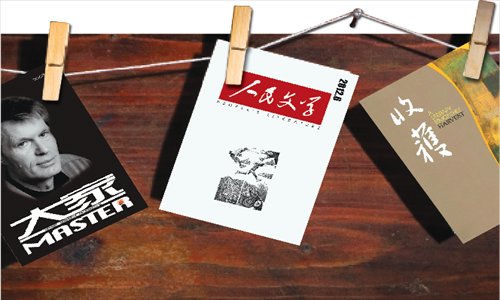

On June 26, Master, a bi-monthly literary magazine published by Yunnan People's Publishing House since 1994, was forced to suspend its operation for illegally running its magazine for commercial interests.

The publication reprinted a second version of "Master," under the guise of the revered literary magazine and published academic papers in exchange for money.

The embarrassing scandal raised questions about the livelihood of other literary magazines, as Master's financial predicament, which presumably led to its actions, is not isolated.

Circulation of US literary magazines like The New Yorker, published 47 times annually, can reach one million.

The Atlantic, a monthly literary, cultural and political analysis magazine, has a circulation of about 400,000.

"But here in China, respected literary magazines like People's Literature, October and Harvest can only sell around 100,000 copies per issue," said Qiu Huadong, deputy managing director of People's Literature.

"But this is not bad, compared to the 1990s."

Ups and downs

Just 30 years ago, domestic literary magazines were still popular. When October, a monthly journal featuring short and long stories first published in 1978, Beijing's literary circle enthusiastically welcomed its arrival.

A month after Chinese writer Liu Xinwu published his short story in the magazine's first issue, Love's Position, he received nearly 7,000 letters from readers.

"The 1980s was a prime time for Chinese literary magazines," said Qiu.

Due to limited channels of information and a thirst for words following strict policies set during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), literature filled the void in people's spiritual life.

"It played an enlightening role for society then," Qiu told the Global Times.

Qiu said that it wasn't until the 1990s when society was affected by materialistic values that literature's grip on people weakened.

"The worst period was between 1995 and 1998, when a quarter of domestic literary magazines stopped or stalled their operation," said Qiu.

For example, Huaxi, established in 1979, changed its focus from pure literature to style and love-themed features in 2000. And Mengya, inaugurated in 1956, transformed into its current campus-novel style in 1999 from its previous focus on literature.

"At that time, many of the literary magazines sold or rented out their edition number," said Qiu. In the last decade, Qiu said interest in literature has resurfaced.

"It's partly due to the government's support in driving the cultural industry, but the main reason is public awareness," said Qiu. "People want to read literature now. It's not such a bad time for us."

There are over 100 literary publishing houses in China, which is more than that in the US, he added.

Funding fiasco

It's not the worst of times, but it's not the best of times either. The Master scandal has ignited concern for the financial situation of other literary magazines. Lack of money is a common thread.

"As far as I know, State-class literary magazines (like People's Literature, October and Harvest) have financial support either from governments or related enterprises," said Lu Min, a writer.

"But there are many magazines that lack financial support, leading to a lower quality of work and a declining circulation, a vicious circle."

While the lack of money is one problem, a shortage of submissions is another.

"Back in the 1980s, quality pieces came out one after another," said Ye Kai, copy editor for Harvest. "Editors were eager to publish."

"But now we have difficulties discovering quality writers. Few pieces really stand out and qualify for our publishing standard."

Ye said that sometimes they have to publish subpar stories, due to the lack of quality work available. Ye attributes this to a current lazy attitude in the industry.

"It's disrespectful for literature," he said.

The emergence of multi-media channels exacerbates their situation. "The publishing aspect of literary magazines is weakening," said Qiu. "Writers now have other ways to publish their work, and readers have a plethora of reading options."

Diversifying content

As the demographic of literary magazine readers in China is a small group compared to the US, insisting on purity versus diversifying content is a predicament many Chinese literary magazines face.

"Harvest will not change its style to cater to the public taste," said Ye.

"We have maintained a steady development in accordance to the current changes in literature and writing," said Chen Dongjie, deputy managing editor of October. "I hope our focus will remain on literature."

"We will not sacrifice the magazine's quality for commercial interests," said Qiu. "We don't want to stick to high-brow tastes, but we'd like to attract more people to have an appreciation for literature." China's reading level remains at the mid-to-low level and needs to be elevated, he added.

Despite holding onto these principles, Qiu admits that diversity is a successful method in dealing with industry changes. Mixing literature with popular culture has witnessed success abroad.

Bungeishunj, a leading literature magazine in Japan, has a history of 89 years. The magazine divides its content into public interests and pure literature section. Taiwan's INK, popular among locals, also offers diversified content, covering literature, play and art comments, complemented by beautiful artwork.

"We will try to keep up with the reading tastes of the times," Qiu said.

Global Times