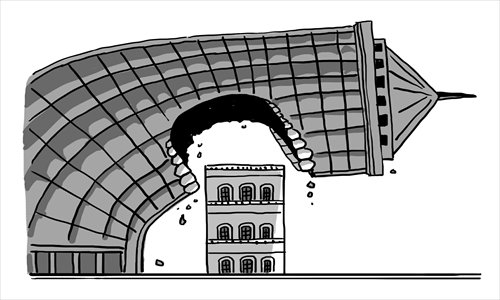

Dilapidated houses are resorts to others

A new book named Disappearing Shanghai was published recently in the US. The book collected more than 80 pictures that Howard French, now a journalism professor at Columbia University, took in Shanghai when he was the New York Times' bureau chief there a few years ago. Qiu Xiaolong, a Chinese writer born in Shanghai and living in St. Louis contributed some poems and essays based on the pictures.

French's photos solely focused on life in the city's dilapidated old neighborhoods. While Qiu, who is broadly acclaimed in the US and Europe for his English language Inspector Chen series of novels, writes elegantly about the hometown he was more familiar with than its skyscraper-defined modern version.

I had some fascinating conversations with both French and Qiu on urban demolition and rebuilding, and on development and preservation.

French was quite restrained when I asked for his opinions. He emphasized that he didn't want to tell Chinese people how to live their lives. Only when I mentioned the happy memories I had when my family moved from the cramped old apartment where I grew up to a brand new one about 20 years ago, did he pause before saying, "You were a college student then. And you had the energy to build up a new life in an entirely new neighborhood. But those people who have spent their whole life in the old buildings and are used to the convenience of the close-tied neighborhood, would they feel happy to move into a modern building where neighbors close doors and don't know one another?"

The old house where Qiu grew up is still in Shanghai, sitting empty. His siblings have all moved out. Some of his old friends still live in the battered houses in the narrow lane, where all the stories in his short story collection Years of Red Dust are based. Since the book was published in 2010, more and more tourists have flocked to the lane.

Qiu said his old neighbors were quite happy at first. They thought it would be finally their turn to face demolition because the houses were so shabby and the authorities would likely feel it was a shame to show them to foreign tourists. But the only changes were periodical renovations of the facades by the government to make the lane look better.

"The neighbors are disappointed. The lane is in central Shanghai. If it's demolished, the relocation fees would make everyone a millionaire. I understand this. But for me, it's old memories. It represents spiritual support. So I have been struggling on what to expect," Qiu told me.

The difference between the views of French, Qiu and people living in the old houses is no surprise.

The idea of architectural preservation was initiated in the West. Although Western-influenced Chinese scholars like Liang Sicheng brought the idea back to China decades ago but it didn't win mainstream support until recently.

The awakening was partly driven by tourism. People now realize as old buildings are becoming rarities that they are more appealing to tourists than ubiquitous skyscrapers.

But commercial interests aside, even sincerely nostalgic people have to realize the complexity of preservation. People are always more interested in things they don't have. Different levels of development offer us different living environments, and, therefore, different views. In other words, when some people are nostalgic those who actually have to cope with the subject of the nostalgia may not share the feeling.

A few years ago, when I learned the W hotel group was planning to build a hotel on Vieques, an island in Puerto Rico that my husband and I frequent for vacations, I was upset. I was worried the W hotel would open a can of worms that would eventually turn the lovely and quiet tropical island into another overdeveloped luxury resort area. But the locals I talked to seemed to be more interested in the job opportunities and the modern life style the W hotel could bring.

In the US, gentrification also gets a mixed response. In New York, for example, residents often fight against new developments in many neighborhoods. But often it's not the homeowners but the tenants who worry about being pushed out by rising real estate prices who make the most noise.

The only thing we may need to keep in mind is that only the locals should get the final say. Their decisions may not be the right ones in the long run and they may regret them in the future. But they have the right to write their own story.

The author is a New York-based journalist. rong_xiaoqing@hotmail.com