Reaping the long Harvest

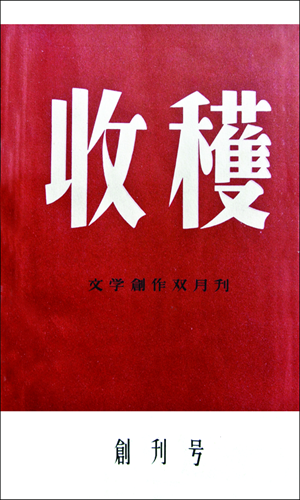

Late in 1978, the veteran writer, Cong Weixi received a letter from the editorial office of Harvest (Shouhuo), a literary bimonthly (six times a year) magazine founded in Shanghai in 1957. The letter informed him that his novella, Red Magnolia Blossoms Beneath the Prison Wall (Daqiang Xia De Hongyulan) would be published in the magazine the following year.

"It was like a fairy tale come true," Cong recalled at a seminar marking the 55th anniversary of Harvest held at the publisher's offices on Julu Road last month.

Red Magnolia Blossoms Beneath the Prison Wall tells the story of Ge Ling, a communist leader who joined the Party during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937-45). Condemned as a "rightist," Ge is jailed in the 1970s and in an ironic twist, he shares a cell with the same bandit outlaw who he brought to justice 30 years previously.

In fact, the publication of this story wasn't just a miracle for Cong, but for the whole of the literary scene in China. Cong himself had been labeled a rightist in 1957, spending years in prison and doing heavy manual labor right up until 1979.

Appreciative editor

Harvest itself has been shut down twice since 1957: the first time during the worst years of chronic nationwide food shortages between 1959 and 1961, and then during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76).

"Even before I submitted the story someone said to me, 'do you want to go back to prison?' But I was happy when I heard that Ba Jin, the Chinese literary giant, had resumed his position as chief editor because I knew that he would appreciate my work," Cong recalled.

When the story finally appeared, Cong, unsurprisingly, felt a mixture of elation and apprehensiveness.

Zhong Hongming, a senior editor at Harvest told the Global Times that, like all publications, the magazine was unavoidably influenced by the political environment during the 1950s to 1960s and that the theme of almost all poems printed in Harvest "paid tribute to workers, peasants and soldiers."

"And during these years, we had to print government editorials, and also the 'literary' works of national leaders of the time," said Zhong. "However, our courage and spirit of innovation meant that we have still played an important role in every transition period of Chinese literature, especially after the opening up of 1979."

The 1980s to the mid-1990s proved an incredibly vibrant period for literature, with writers throwing off the political and social shackles that had previously confined them.

In 1988 and 1989, Harvest released two special issues focusing on young Chinese writers of the time, and whose works were characterized by their innovative and experimental style and forms.

"The influence of these two issues was felt far and wide, and even among practitioners of other art forms in China," said Zhong.

Su Tong was only 26 when his novella, Wives and Concubines was published in Harvest in 1989. It was later adapted and filmed by Zhang Yimou as Raise the Red Lantern (1991).

Yu Hua published Lifetimes (Huozhe) in Harvest in 1992 when he was 32, and which was also adapted by Zhang into a film of the same name in 1994. These two movies are generally regarded as among the most seminal in recent Chinese film history.

Both Su and Yu were also at Harvest's 55th birthday seminar. Su described the magazine as a "lifeboat" rescuing him and his fellow writers and leading them to a "brighter future."

After 2000, Harvest faced criticism, for example when it published the work of Anni baobei (a pseudonym), who became famous for her online literary works. Some older readers complained that Harvest wasn't the place to promote such works. "The reason we insisted on publishing this and similar stories is because online works represented a newly-rising literary force in China at that time. Anni's work has a strong personal style, and she has her own loyal readership."

Market-based reforms

An advertising-free policy is another feature of the magazine that is unchanged since its beginnings and its income is derived solely from the now 15-yuan ($2.40) cover price. "This was the philosophy of Ba Jin," said Zhong. "But we were the first literary magazine to undertake market-based reforms in 1986 and today we assume full responsibility for our finances and receive no government support or charitable sponsorship whatsoever."

According to Zhong, the most "flourishing" yet "difficult" times for Harvest was during the 1980s. In 1980, they achieved a record print run of 1.1 million copies but by 1988, because of a steep rise in the price of paper, they had to borrow money to survive.

"Today, we can basically make ends meet, and our average circulation is about 100,000 copies," added Zhong. Over the years, Harvest has seen many of its competitors go to the wall.

Zhong added that Harvest wants to explore new distribution channels in the future, such as publishing an electronic edition online. "And for the past few years, we've been publishing the work of Chinese writers who are living abroad," she said.