'Water Margin' makes waves

In receiving his Nobel Prize for Literature in Stockholm earlier this month, Mo Yan made a "storyteller" speech about his experience in creating stories. While Mo has now been internationally recognized as a good storyteller, it causes many other Chinese writers to think about how to tell their own stories well.

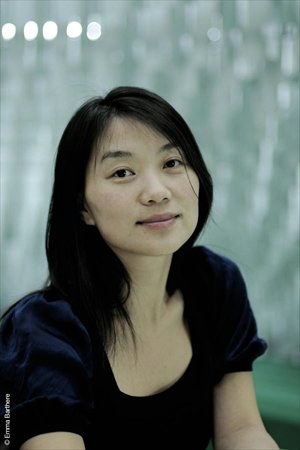

Storytellers usually refer to fiction writers, but the label can also be applied to publishers, translators, filmmakers and other people engaged in communicating ideas. Among them is Xu Gefei, a Chinese publisher in France dedicated to publishing comic books of Chinese stories.

Her new publication of Water Margin, one of the four classics in Chinese literature, has been attracting international attention since October due to French readers' madness about it. "It might be one effect of Mo's prize, which moved world attention toward Chinese literature. But in essence, it is because the story is well told," Xu told Global Times.

New look

Water Margin, a long novel by Shi Nai'an in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), tells of the story of 108 outlaws who rose against feudal oppression and gathered at Liangshan Marsh. It is a well-known story in China and has been made into movies and TV shows many times, but this is the first time it has attracted so much attention abroad. The new publication has been reported by over 20 mainstream French media and media from other countries, creating another wave of interest in Chinese literature after Mo's Nobel Prize.

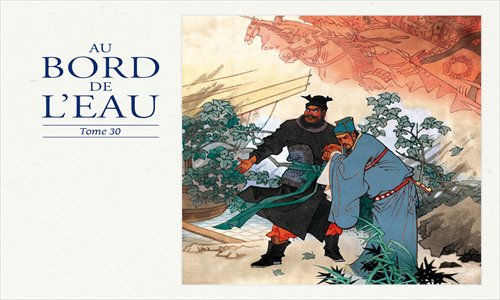

The French version of Water Margin was titled Au Bord De L'eau, so Xu kept the original name in the comic version. The new comics, which consist of 30 volumes, were created based on the traditional comic published by People's Fine Arts Publishing House in 1984.

"It is one of the best traditional comic books ever published in China," said Xu. Her publishing company Les Editions Fei (FEI) bought the copyright two years ago and they spent almost that entire period producing a French version.

She kept the original pictures and has a team to cope with the notes and script. "There were 16 in total, including Chinese and French. "They would discuss the cultural barriers to make it native and acceptable for the local readership," she said. The first 2,500 sets of the story (amounting to 75,000 books) sold out in about six weeks.

Les Lettres Francaises, a paper that covers literature in France, stressed the importance of Water Margin in literature. It said the illustrations in the comic are beautiful and regarded it as a good channel to learn about the story.

Some media found the style of traditional Chinese comic books special, with only one picture per page and with dialog boxes, considering it an acceptable way to tell Chinese stories to French readers who love cartoons.

But as Xu said, the French media are reserved about the end of the story. The comic book ends with the outlaws yielding to the court, which many media regard as due to political factors.

Xu said that the biggest obstacle for Chinese stories going abroad is that foreigners do not understand them, either due to the selection of topics or the narration style.

To her, the set of books is special in that it makes a classical Chinese story appear fresh.

"I've enjoyed comic books since childhood. [This set] changes Westerners' stereotyped ideas about Chinese classics," Xu said, "and for the first time they know there are traditional comics in China similar to their cartoons."

Translation passion

Xu told Global Times that she chose Water Margin partly because the name has an established presence in the book market - the French version of Water Margin was translated well and has been better accepted compared to other classical works. "Translation is a key part in introducing it abroad. It should be excellent in both acceptability and storyline," she said.

The translation of the notes in the comic is regarded as native by many French media.

"The difficulties we experience in translation are beyond imagination for readers," Xu said. In compiling the comic version of Water Margin, one big question was about the length of the script. A single line of Chinese characters usually would be translated into about two lines of French. "The space is rather limited in comic books, so we almost had to recreate the script, with storyline as the priority," Xu said.

To her, French writers such as Romain Rolland and Honoré de Balzac are popular in China mainly because there were years of efforts from Chinese translators like Fu Lei, who loved French literature and were dedicated in introducing it.

One main translator of comic Water Margin is the Frenchman Nicolas Henry, a big fan of Jin Yong's novels. Xu said he appreciates the spirit in Chinese martial arts and fully demonstrates the characters' spirit in the French scripts.

"Scholars could be equally precise, but we worried that the book might turn out dull," she said, "it makes such a difference when one does the same job with passion and interest."

Cross-cultural cooperation

In 2010, FEI published a set of comic books about Bao Zheng, an upright detective and judge who lived during the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). Combining Chinese painter Nie Chongrui's fine illustrations with French playwright Patrick Marty's script of international detective scenario, the set was well received.

France's cultural minister used to write letters to FEI to show his love for traditional Chinese cartoons because of this book.

According to Xu, it was Marty who brought up the idea. He became familiar with the story of Bao by chance in 2008 and was fascinated. To build a vivid and true figure, Marty went to Kaifeng, where the legend starts, as well as Hefei and other areas in China to learn more about Bao.

Xu once wrote in Sina Weibo that introducing Chinese culture should not depend on sheer eagerness. "We need to let foreigners interested in Chinese culture and Chinese interested in foreign culture fall in 'free love' and then give them a push."

"Chinese and Westerners think differently in telling stories and China has a relatively shorter history of storytelling," she said, "Why cannot we keep a large-country mindset and let foreigners obsessed by Chinese culture tell our story?"

Xu established the publishing house in 2009 in Paris with three French partners who love Chinese culture, aiming to introduce Chinese culture in the form of cartoons and comic books. All the works by FEI feature French scriptwriters plus Chinese stories - a combination of both countries' advantage. Besides ancient stories, she also touches on historical topics such as the Nanjing massacre.

She told Global Times that her dream is to produce comic books about the remaining three Chinese classic novels. In the future, she might also set foot in moviemaking and make Judge Bao into an animated film.

"It is a good time for China to vent its voice. The world now pays more and more attention to it," she said, "they are willing to hear as long as it is understandable."

More info on :http://www.globaltimes.cn/NEWS/tabid/99/ID/640419/640419.aspx