Combing through history

On Christmas Day, a museum featuring a special group of women - the zishunü, women who made a vow to remain single and honor that pledge by wearing their hair in a special bun, was unveiled in Jun'an township, Shunde, South China's Guangdong Province.

This is an effort by the local authority to prevent the unique culture of the zishunü from dying out. They are considered as pioneer Chinese women in a nation where, despite "holding up half the sky," women still seek true gender equality. Today, most zishunü died with the elderly survivors now well into their 80s or above.

Dating back to the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), in the Pearl River Delta, some young women coiled their hair into buns at a public ceremony, swearing not to get married forever but to lead a life on their own. Most used this action as a protest against feudal tradition - which forced women to be humble and acknowledge male superiority in their families.

In addition to these women garnering solid incomes thanks to the booming silkworm farming industry in their area, the early touch of the revolution and their dreams of liberation promoted the appearance and popularity of zishunü. According to a program by Phoenix TV, in Jun'an itself, nine out of 10 women declared to be zishunü at the movement's peak.

The trend withered away in the early 1930s as sericulture declined and strife broke out.

Once becoming zishunü, a woman could never go back on her word. Her parents could not force her to marry. If she was discovered to have had affairs with men, she would be severely beaten before being drowned by locals. They were also refused burial in their family's yard or within the village.

Unlike other young women, zishunü could seek work elsewhere. In 1930s, many of them moved in groups to Hong Kong, or Southeast Asian countries like Singapore and Malaysia to work as domestic workers, sending much of their earnings back home to support their families.

As they grew old, their longing for home began to bite. Many zishunü chose to return to their place of birth despite becoming the nationals of foreign countries.

They collected funds together to build group homes. In 1950, the Bingyutang courtyard, which now hosts the museum, was built in Jun'an, funded by more than 500 zishunü, including 400 having worked in Singapore.

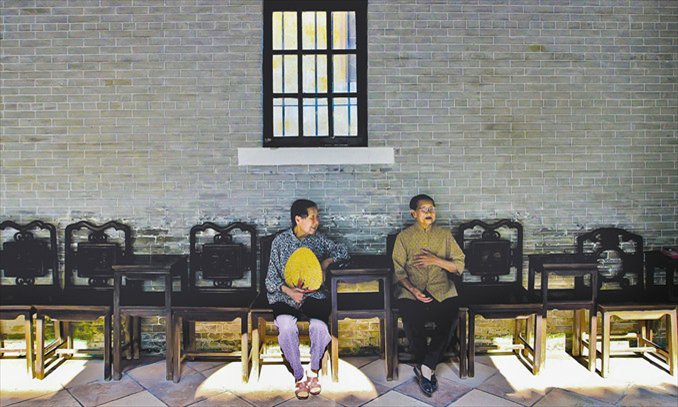

The courtyard used to house over 30 zishunü at one time. But as many passed away or chose to live with their relatives, the Bingyutang has become a site for those still alive to meet and care for the memorial tablets of all their fellows who have passed away.

The statistics show that Shunde still has 76 zishunü. Except for preserving the custom, the local authority also provides them with insurance and a pension, and even helped 12 of them regain their Chinese nationality in 2011.

Now, the Bingyutang has an additional function, to display the zishunü's history to the public. With over 100 objects used by zishunü, such as clothes, utensils, decorations, pictures and paper materials, it welcomes tourists for free nearly every day.

Global Times