US war on terror bent by strategy

The Boston bombings on April 15 shocked the world. As a goodwill measure to show international solidarity in the face of terror, Chinese President Xi Jinping immediately sent a message to US President Barack Obama to express sympathy and condolences. China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs also unequivocally voiced strong condemnation and opposition to the violent attacks against civilians.

However, China's diplomatic courtesy is unrequited after a deadly clash between a criminal gang and the local police killed 21 in Bachu county of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region on April 23, including 15 police officers and six perpetrators.

This incident was quickly characterized as terrorism by the Chinese authorities because of the alleged involvement of Uyghur separatists and terrorists.

When inquired about the US government response to this incident, Patrick Ventrell, a spokesperson for the US Department of State, only expressed a distant regret at "the unfortunate acts of violence" and further urged the Chinese government to conduct "a thorough and transparent investigation," and to protect the human rights of all Chinese citizens, including Uyghurs.

The rather cold and untrusting reply invited a quick pique from the Chinese side. Hua Chunying, Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman, criticized the US government for its lack of sympathy and reluctance to condemn terrorists in China.

This bitter exchange reflects a frustrating fact: Divisiveness in identifying terrorism has put international counterterrorism cooperation in jeopardy.

The Boston bombings renewed international interest in terrorism perpetrated by Chechen separatists.

Although the 1999 Moscow apartment bombings, the 2002 Dubrovka Theater siege, and the 2004 Beslan school hostage crisis had revealed terrorist tendencies among Islamist Chechen separatists, US foreign policy makers never failed to show sympathy to Chechen separatists, due to the Soviet Union's record of religious oppression and Russia's mercilessness in fighting the breakaway republic.

As Steven Pifer, former deputy assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs, articulately put it in 2003, "we do not share the Russian assessment that the Chechen conflict is simply and solely a counterterrorism effort. While there are terrorist elements fighting in Chechnya, we do not agree that all separatists can be equated as terrorists."

Not surprisingly, in 2004, the US granted high-profile asylum to Ilyas Akhmadov, former foreign minister of the separatist Chechen government, despite the Russian government's accusations that Akhmadov had organized terrorist training and armed insurgencies.

Even the US Department of Homeland Security, out of counterterrorism considerations, initially appealed against the asylum granted to Akhmadov by the immigration court in Boston in 2002.

But in the end, inside the Beltway, the US political ideal of upholding human rights and the strategic calculation of constraining Russia won out over the concerns over terrorism.

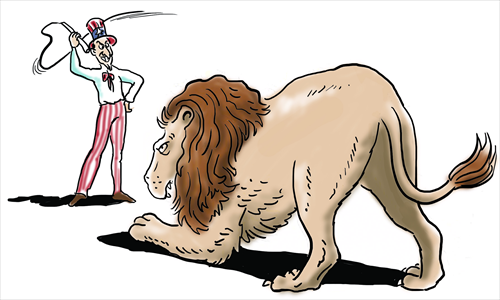

Similarly, the US is treading a very thin line between promoting human rights and stoking Islamic extremism and ethnic separatism in China.

The US publicly endorses the World Uyghur Congress (WUC), a Uyghur group seeking the secession of Xinjiang from China to resurrect the East Turkestan Republic.

On the other hand, to court the Chinese government's cooperation on counterterrorism, the US put the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) on its list of terrorist organizations. However, China claims that the WUC and ETIM are closely associated.

Not long after September 11 attacks in 2001, in counterterrorism that swept on the border of Afghanistan and Pakistan, 22 Uyghur militants were captured by the US and detained at Guantanamo Bay.

After seven years, the US counterterrorism forces had become fully aware that these Uyghurs were ETIM members who had undergone Al Qaeda and Taliban sponsored military training programs.

And yet, they were set free because the Uyghurs claimed to be trained in Afghanistan to fight the Chinese, not the Americans.

But if there is only one country in the world that knows better not to bet on expediential relations with terrorists, it should be the US. During the Soviet War in Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989, by sponsoring the mujahedeen to fight against the Soviet Union, the US eventually created the situation that gave birth to the Taliban.

The US should reprioritize its foreign policy missions and recalibrate its strategies to create a more coherent international front line against terrorism.

The author is studying political communication at New York University. He is an Asia Foundation young diplomat fellow and a graduate of the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, with a major in international relations. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn