Director’s cut

A popular Chinese adage claims women hold up half the sky, although in the theater world female directors languish as relative understudies to their male counterparts. It was this imbalance that last year inspired the inaugural International Women's Festival (IWF), which this year began on April 29.

Under the helm of the Beijing Women's Federation, the month-long festival aims to build a stronger platform for young female theater directors and break the mold of what in China has traditionally been a "boys' club."

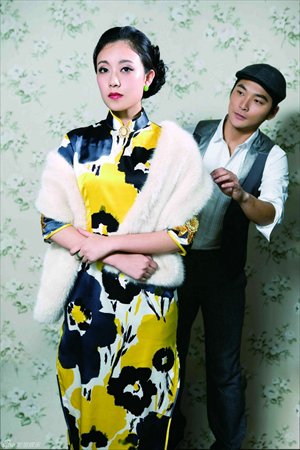

One of the productions being held during the festival is the musical Eileen Chang, which explores the twilight years of one of China's most celebrated female writers. Renowned for depicting the tense relationship between men and women, the musical by female director Yan Yue runs until May 23 at the Dayin Theater in Chaoyang district.

However, Eileen Chang struggled to compete attendance-wise with legendary director Lin Zhaohua's adaptation of William Shakespeare's classic The Tragedy of Coriolanus, which ended its run Sunday at the Beijing Capital Theater. The differing fortunes of the two productions provides an apt snapshot of the male-female divide in Chinese theater.

"There are female figures in almost every theater production, particularly for roles as mothers or wives. But they do not pay close attention to issues concerning women," said Li Jingtian, 28, founder of the IWF.

'Symbolic' presence on stage

More than 350 dramas were staged at Beijing theaters in 2011, although few had lead female characters or directors.

"In many films and theater productions, women play minor or symbolic roles. Just look at the Bond girls in the 007 series," said Li, who is also a playwright and director. "Dramatic conflicts in theater productions often center on male characters, despite the fact that in the UK alone about 60 percent of local theatergoers are women."

Wangfujing, a male-dominated play produced by the National Center for the Performing Arts in 2011, tells the story of Beijing's historic commercial street during the early 20th century. Aside from protagonist Tong Shouchun's wife, who makes a brief appearance at the beginning of the play, the Ren Ming-directed drama features an all-male cast.

Li noted modern issues facing women, including love and the juggling of family and career commitments, are overlooked in many contemporary theater productions.

The IWF features eight dance, drama and traditional Chinese opera productions embracing the theme of "woman, family and love." Spearheaded by both male and female directors from China and abroad, Li hopes the productions will shed light on women in theater without being interpreted as explicitly promoting a feminist agenda.

One of the major reasons women are underrepresented on the stage is the lingering mentality favoring men among directors in China, said producer and director Cui Wenqin.

Cui, 30, heads a team that conducts audience surveys to find out what kinds of stories they would like to see brought to the stage. Suggestions for stories with heroines, however, clash with the story-telling desires of playwrights and directors, said Cui.

"Male directors predominantly prefer stories to be told in an open and direct way, but stories written by or for women are often the other way around," he said. "The story-telling methods among some female directors can be a turnoff for some men in theater."

Among the few male directors who tackle women's topics such as feminism, there is still a preference to cast strong male characters, Cui noted. Even the 2009 premiere of the Chinese version of episodic play The Vagina Monologues directed by Wang Chong managed to draw criticism from domestic feminists.

American playwright Eve Ensler's controversial masterpiece centers on views about sex, love and rape based on interviews with women worldwide, although the choice of Wang as a director caused a stir among some Chinese feminists.

As a man, Wang's lack of personal experience with feminine issues and his disagreement with the original American storyline took the gloss off the play's commercial success.

In a separate Chinese reworking of the play by female students at Peking University, monologues reflected female students' own life experiences.

Away from the theater world, many Chinese film directors have favored strong female protagonists in their movies - even before Disney's 1998 drama epic Mulan. Zhang Yimou's comedy-drama The Story of Qiu Ju (1992), starring Gong Li in the title role, tells the story of a rural woman's quest for justice after her husband is beaten by a community leader.

Despite its ostensible nod to onscreen "girl power," prominent female Chinese theater director Tian Qinxin insists the film is "more about social issues than women."

"Only female directors and playwrights can justifiably represent women on stage," agreed Gu Chunfang, researcher and author of Her Stage: Study of China's Female Theater Directors (2011), adding it is difficult for female directors to alter male playwrights' intentions.

Rise & fall of female directors

While contemporary Chinese theater might be a male-dominated world, historically this hasn't always been the case.

During the early 20th century, pioneers such as China's first female theater director Sun Weishi (1921-68), who studied in the former Soviet Union and adapted Russian classics such as How Steel Is Made based on the novel by Nikolai Ostrovsky, made their mark with revolutionary plays.

Yet over the past decade, female directors have become a rarity despite a growing number of female playwrights. From 1976 to the early 1990s, Chinese female theater directors enjoyed a renaissance.

Names including Wang Jia'na, Lei Guohua and Chen Xinyi, the latter affectionately dubbed China's "drama queen" for productions that tug at audience heartstrings, all made a splash nationwide during this period.

However, today only a handful of respected female directors lead the charge. Among them is Tian, who is with the State-owned National Theatre of China (NTC).

Tian, 45, made her name in 1999 by directing Between the Living and Dead, a drama set in rural China during in the 1930s. Since then she has directed a number of mainstream and commercial plays, with Green Snake based on the novel by Li Bihua the most recent to her credit.

Recent years have seen Beijing's theater circuit dominated by eight young male directors, including Shao Zehui and Zhao Miao. Aside from Tian, who is the only female among the NTC's nine directors, few women have been at the helm of plays that have toured nationally.

Hardships associated with working in theater, including long and inconsistent hours, low pay and pressure from family commitments, have resulted in fewer women breaking through Chinese theater's glass ceiling, according to female director Hu Xiaoqing.

The 31-year-old, who in 2011 was the assistant director of the Chinese version of smash-hit, female-dominated musical Mamma Mia!, insists the lack of proper platforms fostering female creativity is the major reason for the lack of female directors.

But Hu is hesitant to overplay the gender card, noting universal challenges affect men and women in her profession.

"Both male and female directors face the same pressure to make enough money to support their families. Success depends on talent, opportunities and the efforts an individual is willing to make," said Hu, who was part of the Arkansas Repertoire Theater in the US from 2004 to 2008.

Foreign perspectives

Ruth Kanner, artistic director of her namesake Tel Aviv-based theater troupe, observed last year while touring Beijing that the playing field is hardly level for women in theater worldwide.

"The main challenge [facing Chinese theater] is providing room for feminine thinking, images and modes of action that exclude male dominance," said Kanner, whose troupe last year performed At Sea based on stories about love and death.

The biggest hurdle for female directors is starting out, argues Romey Curtis, vice president of the Hawaii-based non-profit theater group Women in Theater.

"Getting that first opportunity to show what one can do … is often a case of sheer luck. There are many [women] who are just as talented as their successful sisters, but never have the chance to prove it," said Curtis, who is also a playwright.

"At the beginning of a career, men perhaps have an advantage. They can be forceful without attracting the stigma attached to an ambitious woman."

While many theater companies overseas offer workshops especially for women, Hu noted in China there are few funded projects for young directors, let alone women.

"There are workshops exclusively for women in New York, but in China there are hardly any," she said.

Looking to the future

Despite the current gender imbalance in Chinese theater, Hu is encouraged by growing opportunities for female directors through events such as the IWF. Another valuable platform for women in theater, the annual Beijing Fringe Festival, is also strengthening their voice.

"So often [theater] is all about money, and subsidies geared toward the advancement of women could be one way to help them on their way," said Curtis.