The devil you know

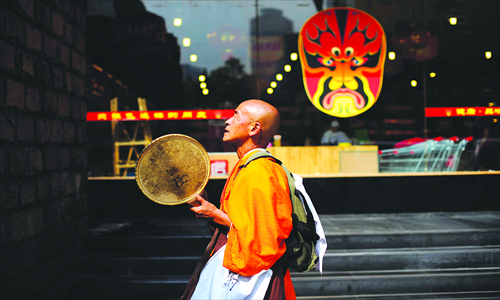

Japanese monk Iwata Ryuzo prays for peace between China and Japan on a street in Chongqing during a tour through China, on May 4, 2011. Photo: CFP

"Hi, I am a Japanese devil."

This was Koji Oikawa's standard greeting to Chinese taxi drivers last year, during anti-Japanese protests over some disputed islands.

Having lived in China for over a decade, Japanese teacher Oikawa, 43, said he uses techniques like this to avoid unpleasant experiences.

"I figured out if I started the conversation in a self-mocking way, Chinese taxi drivers would stop lecturing me about history or asking if I think the islands should belong to Japan or China," Oikawa told the Global Times.

Like Oikawa, about 140,000 Japanese living in China have encountered unpleasant experiences since the Japanese government in September 2012 nationalized the disputed Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea, which are called Senkakus by Japan.

A year ago, Japanese residents lived through thousands of Chinese taking to the streets in protest, smashing and overturning Japanese-branded cars, breaking windows of Japanese restaurants, and burning Japanese flags in cities across China. The past year has been seen as the worst for Sino-Japanese relations since World War II.

To help put an end to anti-Japanese sentiment, recently some 108 Japanese living in China released a book, 108 Japanese People's Reasons to Stay in China, to tell the readers what they really saw and experienced in that year, which they believe has been ignored by the mainstream media from both sides.

Front cover of 108 Japanese People's Reasons to Stay in China

Surprise hit

"The purpose of releasing this book is to record how the lives of Japanese people living in China have been affected in the past year," Junko Haraguchi, one of the executive editors of the book, told the Global Times.

They selected 108 Japanese living in 18 cities in China working as businessmen, teachers, diplomats, photographers and artists to tell their stories about what happened in the past year.

"We asked them to focus on writing their stories, their feelings, instead of commentary," Haraguchi continued.

Haraguchi explained that it was not easy to release a positive book about China. It was refused by several publishers.

However, the book released on August 30 has become one of the most popular items on Amazon in Japan. It has been reprinted twice in a week, and editors are working on its Chinese translation.

Geng Xin, deputy director of Japan's JCC New Japan Research Institute, told the Global Times that he is not surprised the book is popular.

"Japan is an ethnically homogeneous society. It is less likely to trust other ethnicities, therefore it is better to have their own people talk about their experiences in China," Geng said.

"The point is how to make good use of this positive energy to promote relations between two countries," Geng continued.

Bad impression

Many Chinese people are exposed from a very young age to a negative impression of Japan, a reaction formed from history text books that depict Japan's brutal invasion during the Second World War, and negative images of Japan in Chinese media.

As a result, many Chinese express their resentment by calling Japanese troops "Japanese devils" or the nation "little Japan."

As the tension between the two countries continues, a survey found Chinese and Japanese are holding the least favorable view of each other in over a decade. Up to 92 percent of Japanese people said they have a bad impression of China, while 90 percent of Chinese said they have similar feelings about Japan, according to a recent poll conducted by Japanese think-tank Genron NPO.

The pictures of scenes from China's anti-Japan-themed TV dramas in the first pages of the book are the manifestation of this resentment. Since the demonstrations, over 70 out of 200 TV dramas broadcast on national TV stations in 2012 had an anti-Japanese theme. Meanwhile, to satisfy revenge fantasies, about one billion "Japanese devils" were killed off in 2012 on screen at Hengdian World Studios, China's Hollywood, according to Guangdong-based Yangcheng Evening News.

Japanese actor Koji Yano, 43, who has built a career in China's entertainment industry over the last decade by playing roles as a ruthless Japanese solider, is one of the contributors of the book.

Last September, his appearance in a TV drama was cancelled, and a TV show "Day Day Up" he has co-hosted since 2008 suspended his appearances. During that time, he said he suffered from insomnia due to high pressure and anxiety. Many Japanese actors in the Chinese mainland went back to Japan or moved to other places like Hong Kong or Taiwan. He chose to stay.

"Many ruthless Japanese soldiers in TV dramas are played by Chinese people. They are absolutely villains. But the Japanese soldiers I play self-reflect about the war," he wrote.

Teacher Oikawa had the similar experience. Most of his Japanese classes and speaking tours were suspended for two months. Sometimes, the posters for his events were "stolen" overnight. And he often had to cancel the Q&A part at the end of his speeches in case Chinese students asked him political questions.

"I often start my speech saying I am not here to talk about politics and history, but how to study Japanese and how to find a job," he said. "I think that is more useful for students."

For years, Oikawa has been very careful to avoid showing up on a special date in a special city. For example, September 18 marks the anniversary of Japan's invasion of northern China and December 13 marks the anniversary of the Nanjing massacre that killed over 300,000 Chinese by Japanese troops in 1937.

In the wake of violent protests last year, the Japanese Embassy informed its citizens through e-mails to stay indoors. Oikawa's friends and family said they are worried about his safety and asked him to return to Japan.

Oikawa said he can understand China's reaction, but he cannot understand the Chinese concept of "patriotism."

"Chinese people say they love their country, they wear T-shirts which say 'I love China,' but if they have the money they move abroad. I can't help but wonder what patriotism really means to them?" Oikawa asked.

Nevertheless, Oikawa decided to stay. "It is Chinese people who get me into trouble. It is also Chinese people who help me out of trouble," he said.

Japanese cycling enthusiast Kawahara Keiichiro, whose bicycle was stolen and recovered during a China tour in early February, carries charitable goods to be shipped from Beijing to Yunnan Province, on October 24, 2012. Photo: CFP

Finding life's meaning

The main reason why these Japanese choose to stay in China, Haraguchi said, is because all of them have found what they really want to do in life.

Tamako Sato, 51, wanted to be a photographer when she was little. She came to China to study Chinese in 1997 and fell in love with Chinese culture.

She remembered life back in the 1990s in Japan was quite stressful. "People spent too much time on working and only four hours on sleeping, while in Beijing I could spend four hours making dumplings with my friends," she told the Global Times.

Because professional Japanese photographers were rare in China, Sato moved to China to become a freelance photographer. Unlike Western photographers whose work mainly focuses on poverty, her work focuses on happiness.

"Words like air pollution and corruption always make headlines. Those are not the whole picture of China," she said.

In the past 17 years, she witnessed many ups and downs between two countries. She said the idea of going back to Japan ran through her mind only when SARS broke out in China in 2003.

"I think people like me are needed when the relations between the two countries chill, because I can understand why Chinese people think and act in this way and their misunderstanding," she continued.

Fighting ignorance

Xu Jiaju, a professor of Japanese language at China Foreign Affairs University, told the Global Times that the key to improving Sino-Japanese relations is people-to-people communication.

"As long as people from both sides keep communicating, we can still see hope for improved relations," Xu said.

However, many Japanese said it was not easy to make Chinese friends at first. Kunio Nakayama, 34, creative director of Japanese music production company Truly, Inc, softened the attitudes of a person who hated Japanese people through karaoke.

When Nakayama first came to Beijing to study Chinese in 1999, his Chinese friend brought along with him a woman who disliked Japanese people. She shouted at Nakayama the moment she met him. Later when they found out he could sing karaoke in Chinese, her attitude towards him changed.

Since then, Nakayama realized the power of music and decided to join the music industry. Over the years, he has helped introduce Chinese singers to Japan and helped Japanese singers to do shows in China.

"We cannot change what happened in the past. What we can do is to get to know each other now," Nakayama told the Global Times.

Understanding their days in China might not go smoothly in the near future, instead of saying, "I will make you happy forever," Oikawa proposed to his Japanese wife saying, "Let's eat bitterness together the rest of our life," a Chinese way of saying "endure hardships."

And she nodded and replied, "Let's eat bitterness together."

Zhao Jingshu contributed to this story