Toxic relations

Japanese personnel join the effort to dispose of chemical weapons found in Qiqihar, Heilongjiang Province, on June 17, 2004. Photo: CFP

The discovery of some 1,500 bombs on a construction site near a primary school in late September in Qiqihar, Heilongjiang Province, triggered a new wave of outrage over Japanese troops burying chemical weapons in the ground before retreating from China at the end of the World War II.

Emotional discussions once again filled online forums, denouncing Japanese's chemical warfare on Chinese and urging the Japanese government to speed up its promised cleanup of the weapons.

It is estimated that the Japanese army launched 2,000 chemical attacks on Chinese during its invasion from 1937 to 1945, causing over 80,000 casualties.

No one kept track of the locations where these weapons were buried. As a result, many Chinese have fallen victims to the chemical weapons as China speeds up its urbanization with an intense surge in new construction. After almost seven decades, the legacy of Japan's chemical weapon program still casts a shadow over the countries' relations.

Buried problems

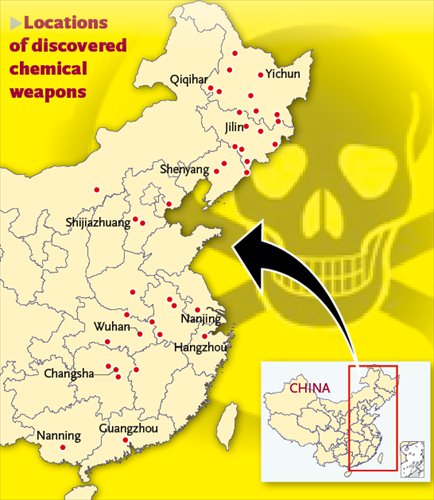

Chemical weapons including bombs and mustard gas were left in 17 provinces, in over 70 areas across the country. The majority of them were left in Northeast China. Official figures put the number of abandoned Japanese chemical weapons at 400,000.

After many years of negotiations, the two governments signed an agreement in 1999 to start the disposal project. Under the agreement, Japan provides money, technology and facilities to dispose of the chemical weapons.

Considering the fact that many of the weapons are rusted or started leaking when they were excavated, governments from both sides reached an agreement to dispose of them in China instead of taking them back to Japan.

The abandoned weapons are estimated to have caused over 1,000 causalities from 1949 to the early 1990s. The number dropped dramatically, to dozens, after the disposal project began. The biggest recent tragedy was in 2003 when five barrels of mustard gas poisoned 43 people and killed one when workers began excavating a construction site in Qiqihar, the hardest-hit city by unearthed chemical weapons.

"Chemical weapons abandoned by Japan in China have posed a huge threat to the safety of Chinese people, property and environment," said Cai Hong, deputy director-general of the Office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for Chemical Weapons Abandoned by Japan in China. The office has been working with the Japanese for decades.

However, progress on destroying chemical weapons remains slow. Japan failed to meet the deadline of completing the disposal procedure in 2012, but it has promised to continue to fulfill its obligations until 2022 to destroy all the unearthed weapons.

"Chinese people might not understand why Syria could probably dispose chemical weapons in 10 months, while it takes China and Japan over a decade to do that," said Cai.

"The work has no precedent in human history," he said. "Unlike American and Russian weapons which are kept in storage, the chemical weapons abandoned by the Japanese are hard to locate."

Cai explained that everything was in chaos during the retreat. Some Japanese soldiers just followed orders to bury things, not knowing what they were.

Locations of discovered chemical weapons. Graphics: GT

Lost memories

In 2004, two Japanese veterans in their 80s went to Dunhua, Jilin Province, to identify the burial positions but found nothing. Over the years, some other Japanese veterans tried to help find buried weapons, but none of them were able to find anything.

Moreover, it takes a long time to identity whether an unearthed munition is a chemical weapon or not, because over 70 years many of them are too corroded to read, he added.

"We are under more pressure than the Japanese side," Cai said. "It is happening in our land to our people. We are the ones who have to bear the consequences, and therefore we don't want to misjudge any possible toxic weapon."

The unearthed chemical weapons continued to cause casualties even in recent years. In 2004, two school boys from Dunhua were injured when they uncovered a chemical weapon while playing near a river close to their village. They reportedly opened the rusted weapon out of curiosity, and were wounded by liquid splashed onto their fingers and legs.

To reduce the number of casualties, Cai's office warned local governments and citizens not to deal with suspected toxic weapons on their own. Perhaps as a result, ever since 2008, no injuries have been reported.

Many Heilongjiang citizens reached by the Global Times said they don't worry about the weapons.

"I have heard of them before, but their existence doesn't really affect our life that much," said Yang Rui, 24, a local resident. "But we are still waiting for an apology from Japan."

Cai explained the low level of public concern is because his office has been keeping low key so it does not trigger public panic.

Denial

Ever since 2003, when the tragedy of Qiqihar made national headlines, Bu Ping, now the director of the Institute of Modern History of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and a researcher on chemical weapons left by the Japanese, has been collecting the evidence of Japanese chemical warfare during the World War II.

One time when he was visiting a place in Japan where thousands of Chinese were forced into labor, he told his Japanese colleagues he was collecting evidence of Japanese chemical warfare. His Japanese friend later sent him 20 drawings that detailed how chemical weapons were made in Japan.

"Some Japanese also fell victims to their own chemical weapons," Bu said, explaining that for this reason some Japanese people want to put information about the program on the historical record.

Some Japanese argue that these chemical weapons are not fatal - they are "civilized weapons" for crowd control or immobilizing but not killing troops. But Bu argued that when Japanese troops intentionally threw the toxic weapons into the underground tunnels where Chinese people were hiding and thus killed all of them, the non-fatal weapons became fatal.

"I remembered I had a huge headache. I could barely breathe. We were told to drink our own urine if we were attacked by toxic gas," Wang Junjie, one of the survivors of Japanese attacks in 1942 in Beitan village, Hebei Province, said in a documentary.

"The urine did not really work, people fell down one after another inside the tunnel," he continued.

Wang Liuzhu, 75, a consultant to an association for the laborers who spent 20 years searching and documenting survivors of forced labor in Henan Province, told the Global Times that some Japanese right-wing groups still want to cover up their crimes in the past.

"Their attitude toward historical problems is negative, always trying to cover up or delay until all the witnesses die," Wang said.

Since 1999, the Japanese government has spent billions of yen (tens of millions of dollars) on the disposal project. However, claims for compensation by ordinary Chinese injured while handling or digging up these weapons have never succeeded. The explanation provided by a Japanese court is that China renounced its demand for war reparations from Japan in the Japan-China Joint Communique of 1972.

Su Xiangxiang, a lawyer who was engaged in a compensation suit for Chinese victims, told the Global Times that the claims for compensation have halted since 2003.

"The case is so sensitive between the two countries that I don't see any hope of winning," Su said. "But I will still keep trying to find a way out."

Bu said even though the claims failed, the Japanese government is taking a positive attitude toward history and shouldering its responsibility to clear up the weapons, which he said is a victory.

Healthy cooperation

Bu said the opinion of some right-wing groups does not change Japan's official statement that Japan will help China to clean up the remaining buried weapons.

In the past three years, a total of 35,000 chemical weapons were retrieved and disposed. In 2010, a project of using mobile destruction equipment to do excavations started in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province.

China has expressed concerns about the arsenic generated from the arms during the disposal procedure. Arsenic does not break down into harmless components over time and could leak into the soil and cause health risks. An agreement has yet to be reached over whether arsenic will be sent back to Japan or sealed in an underground site in China, Cai said.

The deterioration of relations between the two sides, due to an ongoing territorial dispute, has made the work of digging chemical weapons more sensitive, said Cai, who is worried it might trigger more public anger toward Japan.

"One time, a local authority posted a picture of workers transferring the chemical weapons from one place to another. It immediately outraged some Web users, who asked, 'Why don't we send it back to Japan?'" Cai said. "So we have to deal with the public's emotions very carefully."

Zhao Jingshu contributed to this story