Vanished into thin air

Security guards ride through the deserted factory at Shuihou village, Tangshan, Hebei Province. Photo: Li Hao/GT

The steel mill boomed, she says.

"My husband and son worked at the Xingye Industrial factory across the street," Liu Donglu says proudly.

That was 10 years ago.

Back then, Liu says, at least one person out of each of 400 families in the village of Shuihou worked across the street in Kaiping district, Tangshan, Hebei Province.

The Shuihou plant shut down in April.

In response to demands from Beijing for reduced air pollution, the Hebei government in October launched "Operation Sunday" where teams of provincial officials attached explosives to private steel plant boilers and blew them up all over Tangshan.

After that, the old steel workers left the Tangshan area in search of new jobs.

On top of lost factories and lost jobs is lost money: some villagers lent their savings to steel mill owners.

As China and Beijing finally faces up to air pollution so hazardous it makes headlines across the world, it is the humbler regions surrounding the capital city that are paying the price by cutting their own heavy industry.

The Ministry of Environmental Protection in September ordered Hebei Province to slash 60 million tons, or one-third, of its steel production by 2017: Tangshan must cut 40 million tons, Handan 12 million tons and Shijiazhuang 2.8 million tons.

Air pollution prompted the decision. Seven of China's 10 most-polluted cities are in Hebei, dotted around Beijing, according to ministry data released in December.

Village victims

Liu has petitioned multiple levels of government: from her village committee right up to the State Bureau of Letters and Calls in Beijing in October. Her family lent about 100,000 yuan ($16,525) to the private Shuihou steel plant.

Liu's neighbor, surnamed Chen, has a son and a daughter who both once worked at the mill. Today the young man is unemployed, while the daughter found a job outside the area.

Their family ploughed about 400,000 yuan into the plant. Chen would not reveal her full name.

The sky was darker before, Chen says. "You could taste the coal and smoke."

Like many in the area, the Shuihou steel mill was a small, private operation. Environmental protection did not feature prominently in the firm's short-term portfolio. Now the villagers who rented out the land are left to clean up the mess.

"We put our whole life's earnings into that steel mill," Chen says. "We hope the government can do something about it."

The Shuihou village committee building, once a bustling government office, is now vacant and littered with trash. The committee members vanished, villagers say. The former factory owner does not answer his phone.

"The most difficult issues are paying debt and solving land disputes," an anonymous official from the Kaiping district government in Tangshan told the Economy and Nation Weekly in December.

Kaiping officials wrestle daily with the issues of unskilled, unemployed villagers searching for work. The district's economy relies heavily on heavy industry and declining opportunities.

Most of the disused industrial land is unfit for farming. In the case of Shuihou, the abandoned factory building remains standing after it closed in April. Demolishing the factory will not necessarily make that land usable or profitable.

"The fields provided us with food and job opportunities before the factory opened," Chen says. "Now we can't go back to farming anymore and we have to find new jobs."

Some factories in the Tangshan area are still operating, although most have been closed. Photo: Li Hao/GT

Hazardous environment

It's extremely unlikely such land is fit for cultivation, says Gong Yuyang, managing director of ESD China, an environmental engineering company.

"If the factory was built on the land for only a short period and had effective protection, if the soil were not heavily polluted, then it could be reclaimed," he tells the Global Times, "but that situation is rather rare."

Li Shuyou has been leading an island lifestyle for about nine years: his house in Xiaotun village, Fengrun district of Tangshan, stands almost alone, surrounded by private factories. There's not a day he comes home without smelling pollution in the air, he tells the Global Times.

The villagers in Xiaotun have no good drinking water and rely on bottled water. There's a well, but the water quality is terrible, Li says.

The death of the factories in October inspired a little hope, Li says. The well water is already much better, he believes.

Steel mills pollute not only water and air, Gong says, but soil as well: "heavy metal, aromatics, petroleum-related, inorganic and sulfide stains," he lists.

Heavy metal harms soil and poisons crops with hazardous substances, Gong explains.

"Pollutants enter the human body by means of breathing, body contact or food ingestion," Gong says. "Once it accumulates in the body, it greatly increases the risk of cancer."

Illegally high levels of poisonous heavy metals were found in southern Chinese rice in May last year when eight out of 18 batches of rice tested by authorities in the southern province of Guangdong were found to contain excessive amounts of carcinogenic heavy metal.

In response, Guangdong took the unprecedented step of naming those rice producers whose products contained "excessive amounts" of cadmium.

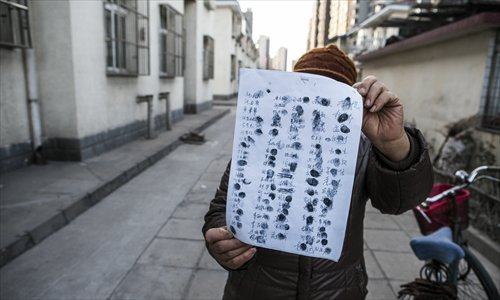

Liu Donglu holds up a petition signed by Shuihou villagers trying to get back money they lost to the factory shutdown. Photo: Li Hao/GT

Land reclamation

The government needs a plan to address these issues, says Li Xinchuang, president of China Metallurgical Industry Planning and Research Institute.

"The government should arrange for reemployment opportunities," he tells the Global Times. Industrial wasteland should be converted for use by other industries, he suggests.

It took five years for Beijing Shougang Steel Company to complete its 2005 move to Caofeidian, Tangshan. The land Shougang left behind in Shijingshan district sits idle.

"After the move, the government cleared up the obvious pollutants and the heavily polluted soil," Gong says. "Then research and evaluation of polluted soil was performed. Right now the work hasn't been finished and the results aren't open to the public at the moment."

Talks persist over what to do about Shougang.

In September last year, the Beijing Daily reported the dead steel plant would be converted into a tourist attraction set to open in 2014.

In October, the Beijing-based Legal Mirror reported plans for a financial district, shops and entertainment center.

Today, nobody is talking about Tangshan.

"There's been partial research in Tangshan about how to remediate the wasteland," Gong says, "but there's been no full survey or evaluation of all the polluted land yet."

A gatekeeper at one of the deserted Hebei Province factories, Xinhaixin Steel Industry, says even though the factory has been shut down for about six months, the site won't be torn down or cleared for a long time.

"There are still people coming to buy the leftover steel industry equipment," he says. He doesn't know what will happen when all the equipment has been sold.

There's simply no time to think about abandoned industrial wasteland at the moment, an official from the Tangshan Environmental Bureau told Caijing magazine in July.

Most steel plants rented agricultural land from villages like Xiaotun and Shuihou. The companies exited, leaving behind poisoned land. Only the buildings remain, where buyers occasionally pick over the rusting equipment.

After Tangshan steel companies Xin'ao and Taifeng shut down before the 2008 Olympics, the government couldn't even identify all the locations of all the disused industrial wasteland, Caijing reported.

Marooned villager Li Shuyou attends to 40 sheep. He wants to expand his flock into the deserted factory.

Li listens, watches and waits for news of factory demolitions, pollution clean-ups or land reclamation.

"I think it will take many, many years," he says.