A touch of class

Editor's note

From a fishing village with a population of just 200,000 in 1843, Shanghai has developed into a huge modern city where more than 23 million people live. From the time Shanghai was forced to open up as a port in 1843, the city has witnessed remarkable change and progress. This year marks the 171st anniversary of Shanghai's opening-up and in this special series of reports, the Global Times will highlight some of the crucial moments, recall some choice memories of olden days and uncover some of the secrets of the city. Don't miss these exciting insights into the metropolis.

Modern Chinese students dressed in school uniforms from the Republic of China era Photo: IC

The images of women in old Shanghai that spring to mind usually feature exquisite young women in beautiful qipao. But these pictures overshadow the reality of the early days when women suffered foot binding, backward thinking, oppression and lived in a society that gave them few rights.

After Shanghai opened its port in 1843, the arrival of Western ideas meant Shanghai women were the first in China to be exposed to Western perceptions of women's rights, and the second half of the 19th century saw an awakening and blooming for women in the city.

During the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) and the early years of the Republic of China (1912-1949), a new group of women emerged in the city: female students who had been living in Shanghai and experiencing Western culture and influences.

The first school for girls in Shanghai was the Bridgman Memorial School for Girls, established in 1851 by the American Episcopalian missionary Elijah Coleman Bridgman. The school was located near the West Gate, on today's Fangxie Road.

Home education

In feudal China, women could only be educated at home and this education was limited to social rules, family traditions and domestic skills with an emphasis on the women becoming virtuous wives and mothers. Because China lacked a tradition of women attending schools, the first few women's schools in Shanghai struggled hard to find students. To promote women's education and attract students, many schools admitted students for free and some offered subsidies as incentives. Most of first students enrolled at girls' schools in Shanghai were orphans or from low-income families. The Bridgman Memorial School for Girls had only 20 students when it opened.

In 1876, the newspaper Shenbao published a series of editorials and articles discussing women's education in Britain, the US and Germany, written by forward thinking Chinese scholars like Liang Qichao. The pieces argued that as women comprised about half the population, their education was important not just for the women themselves but for the future of all China; and that women's education should not be confined to their domestic responsibilities, but should include practical and academic studies like astronomy, geology, arithmetic and other sciences. Women should be empowered by knowledge and become teachers, scientists and members of the professions.

In 1903 a pamphlet entitled "The Women's Bell" by historian and educator Jin Tianhe probably put the first major systematic argument for women's rights in China. Jin attacked old practices like foot binding, saying that this not only limited women's mobility but also weakened the Chinese nation, and he argued that men and women were born equal. He advocated free marriage and women's rights to education and politics. The book was sold out in a few months after it was published by the Shanghai Datong Publishing House, and had a lasting influence on discussions on women's rights in Shanghai.

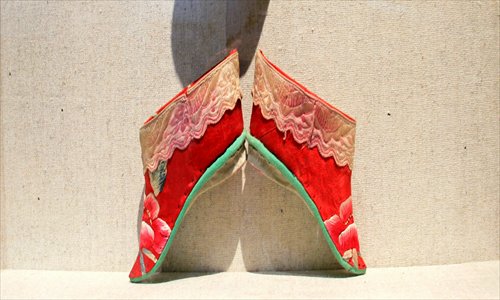

Some of the different styles of lotus shoes to be worn by women with bound feet Photos: IC

Selling Modernity

With Shanghai becoming more accepting of education for women, from the 1880s girls' schools gradually became more popular with the city's wealthier families. More schools, such as the Qingxin Girls' Middle School (or the Mary Farnham Girls' Middle School), the St. Mary's School for Girls and the Methodist Girls' High School opened between the 1860s and 1920s. In the book Asian Women and Intimate Work Wu Yongmei wrote in her chapter entitled "Selling Modernity" that these missionary schools, as a part of their missions, offered Western-style educations to girls from wealthy families.

By 1897, there were 12 missionary girls' schools in Shanghai, about a third of all the girls' schools in China, and by 1900, the number rose to 16, including 12 primary schools, three middle and high schools and a college. The schools charged tuition fees that only upper class families could afford. The subjects included Christianity, English, Chinese, math, music and domestic science. Domestic science covered a variety of topics including beauty, interior decoration, personal skills, guidance in selecting a husband, etiquette and how to organize a family, as well as embroidery and cooking.

The most prestigious girls' school in Shanghai was probably the McTyeire School for Girls, founded by Southern Methodist missionaries in 1892 to provide a Christian education for Chinese daughters of "the well-to-do classes." The most famous alumni of the school were the Soong sisters. Soong Mei-ling and Soong Ai-ling apparently entered McTyeire when they were just 5, and Soong Mei-ling mastered English and became incredibly fluent at McTyeire.

In a paper entitled "Historical Memory, Community Service, Hope: Reclaiming the Social Purposes of Education for the Shanghai McTyeire School for Girls," US educationalist Heidi Ross concluded, "Privileged and cosmopolitan backgrounds, coupled with unparalleled English fluency, set McTyeire students apart, made them feel special, different, entitled 'McTyeire girls.'"

In 1952, McTyeire was consolidated with the St. Mary's School for Girls, the alma mater of writer Eileen Chang, and renamed the Shanghai No.3 Girls' School. Today, the school is the only girls-only high school in Shanghai.

The first Chinese-funded and run girls' school was the Jingzheng Girls' School established by Jin Yuanshan in southern Shanghai in 1898. The school discouraged foot binding, and its first students were some of the first women in Shanghai who had untied their bound feet.

The school taught traditional Chinese literature in Chinese and science in English. Students were also taught physical exercise, sewing and musical instruments. The first locally operated school however was opened for only two years. After the Hundred Days' Reform movement failed, Jin, a reformist, fled being wanted by the Qing government. Later he served as an education official for the nationalist government and a respected professor.

Some of the different styles of lotus shoes to be worn by women with bound feet Photos: IC

A big step forward

In 1907, the Qing government officially included women's education in its education system and girls were no longer barred from public schools. Women were given the right to four year blocks of education in primary school, then high school and finally college. Although this was a big step forward, it was less than men who were entitled to five years in each of the schools. And women were not allowed to attend the same schools as men.

Women's education progressed after the Nationalist government took over in 1912. After the May Fourth Movement in 1919, primary schools accepted boys and girls in the same classes. Middle schools started to admit girls too, but many schools still separated boys and girls into different classes and in different campuses, in the belief that boys and girls studied for different purposes.

Records show that in 1935, 9,599 female students were enrolled in middle or high schools in Shanghai, 29.8 percent of the total number of students.

After the liberation of Shanghai in 1945, all middle schools admitted girls and boys but there were still 15 girls-only schools in Shanghai. Known mostly by numbers (the Shanghai No.1 Girls' High School up to the Shanghai No.12 Girls' High School accounted for 12), most of them were reconsolidated from the leading missionary and locally operated girls' schools. From the 1970s, most of these girls' schools were no longer single-sex institutions.

Although primary schools and middle schools for girls emerged in 1851, there was a scarcity of colleges and universities accepting women in the late 1800s. In 1908, the drought was officially broken when the first college for women, the Shanghai Women's Sports College opened.

In 1912, the Nationalist government officially recognized women's rights to higher education. From the 1920s to the 1940s, 24 colleges for women were established in Shanghai, most of which were specialist schools for sports, arts and medicine. The number of female students in university-level educational institutions rose from 1,574 in 1929 to 4,337 in 1949.

As well as women's schools, the rise of women in society could be seen from the number of women's publications which began emerging in 1898. The first women's publication in China was The Women's Education Paper, founded by Li Run and Huang Jinyu, the wives of the reformists Tan Sitong and Kang Guangren.

Equal rights

All of the major contributors to the paper were women and their names were published on the front page of each edition. The paper promoted education for women and equal rights. It also published stories on new technologies in the industries which employed women like textiles and encouraged its women readers to find work.

Women's magazines flourished too, often presenting feminist viewpoints. Magazines like New Women, Women's Voice, Women's Weekly and Women Magazine began flourishing in 1902, and it was fashionable for women to read these. Before the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, more than 183 women-oriented papers and magazines were being published in China.

In the meantime women had been playing a major role in the city's police force. Policewomen searched women accused of crimes or the many female thieves and smugglers who frequented the train stations, bus stations, piers and hotels.

They helped women and child victims and part of their work involved inspecting foot binders and making them stop. Foot binding was banned by the Nationalist government in 1912 and if a woman refused to untie her feet, the policewomen would fine her and ensure that their orders were carried out.