Liberal leanings

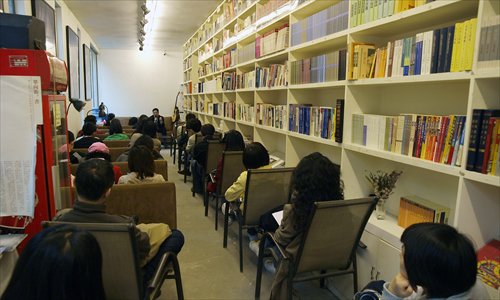

Readers attend a book seminar at One Way Street bookstore in Beijing. Photo: CFP

Chen Ye is perhaps an unlikely advocate for universal values. Unemployed, he has received no university education, and doesn't seem all that interested in making a name for himself.

The 33-year-old has been running a website for over five years providing videos or recordings of lectures and speeches given by liberal intellectuals.

The website, lawstars.org, is purely not for profit and is maintained by Chen almost single-handedly. Its sole purpose is to share video or audio recordings of lectures by mostly liberal scholars. The website makes no attempt at being subtle about its purpose. Four Chinese words at the top of the front page say: "Freedom, democracy, constitution, human rights."

But Chen isn't the only person in China trying to spread what some might call "universal values" in a defiant but non-confrontational way.

Chen has collected over 1,000 lectures since 2008 and has published close to 400 online. Some of the words that jump out from the "tag cloud" on his website include "history," "law," "civil society," "intellectuals" as well as names of top Chinese universities and prominent professors such as He Weifang, an outspoken law professor at Peking University.

In fact, you could say that it all started with Professor He.

Between late 2006 and early 2009, there was a group on social network website Douban dedicated to He Weifang, who has publicly criticized the higher education system and academic corruption. He Weifang himself also later joined the group, posting articles and joining discussions and drawing more fans to the group.

The group was shut down by Douban in early 2009 when it had over 2,600 members. The notice from Douban said the topics under discussion were not allowed or welcomed according to the community's guidelines, according to a letter users posted online.

It was at about this time that Professor He was transferred to a university in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

When the group was shut down, many former members lamented the fact that so many resources had been lost. Chen said he had stored quite a lot of them and started to share them with others.

The latest lecture recording Chen posted on his website was on the "Intellectual youth during the Cultural Revolution" by Michel Bonnin, a French scholar and professor at Tsinghua University.

There were other lectures, with titles such as "Political consideration in civil lawsuits," "Rule of law in China" or "Justice." There is nothing that might immediately give authorities cause for alarm, but the discussions are almost always liberal-oriented.

Chen selects only lectures or talks that are public and uploads them only onto domestic video sharing websites.

"That way, the lectures would have already been screened by the university and education authorities and the websites, which would mean they have the highest chance of surviving," said Chen. He said using sites that require proxies to visit would defeat the purpose of letting more people see them.

For safety, Chen doesn't provide transcripts of the lectures, nor does he encourage discussions on the website. Censoring texts is easy but in a two-hour lecture, the sensitive content may only make up a very small part, and the authorities may not have the patience to listen to the entire lecture or speech, explained Chen.

In the guideline section on his website, Chen asks users not to reply or comment on lectures. There are only a few comments on his website, despite his QQ chat group having over 400 members. While the chat group isn't constantly abuzz with comments, members do sometimes post new lectures and strike up discussions on Mao Zedong or history.

For more vibrant discussions, Chen recommends that users go to other platforms, including kdnet.net, a Hainan-based website that some see as the exact opposite of rightist website Utopia. The editor-in-chief of the website, who goes by the name Mu Mu online, disagrees though. He describes kdnet.net as a "neutral platform with a relatively high concentration of liberals."

Another platform is "Athens Academy," a website mainly serving law students and professionals. Its slogan roughly translates to "Universal rule of law; creating a thinking China." The website allows any user to write blog posts and join discussions on topics related to law. It has been shut down twice since it was founded in late 2005.

Humble beginnings

Chen graduated from a vocational school where he did computer studies. He later became a low-level clerk at a local court and studied law by himself. He has been unemployed for the last five years.

Chen was introduced to intellectuals like He Weifang through their newspaper columns, which he read almost religiously. "I was trying to learn more about the economy through those newspapers, but who'd have thought my attention would be directed to the public sphere?" said Chen.

Since 2008 he has used three different blog service websites, which have either been blocked or were so unstable as to be virtually useless.

On November 24, 2011, Chen started to raise money among Net users to build a website. He said the first donation came in at 10 am that day, indicating that he had some loyal fans. In two months he raised a little over 3,000 yuan ($495).

He has continued to raise money online to cover costs for domain name renewal, website maintenance, and purchase of lectures or reimbursements for students who shared their resources. Small donations also came trickling in. He also sells portable hard drives or flash decks that contain hundreds of lectures and uses some of the proceeds to maintain his website.

By the end of last November, he had received over 14,400 yuan, according to the budget he published.

Law stars club

The name of his club, fa xing she (Law Stars Club), sounds similar to the Chinese translation of Agence France-Presse, which lends the name a certain catchiness, according to Chen.

The other reason, he said, was that he hopes those who follow the club will become "a healthy force in pushing for rule of law in China."

Despite widespread criticism that Chinese people don't read books any more, surprisingly there are more book clubs these days, both online and offline. Most of these book clubs are an extension of publishers, magazines or book stores. The Chinese Museum of Finance has been hosting reading club events since 2011, inviting heavyweight entrepreneurs and decision-makers in the financial and business sectors to recommend books to readers.

In comparison, Chen's "book club" was nowhere near as elitist or as organized.

With a little extra money in hand, Chen said that's when he thought of starting an "online book club." He uses the money people donated to buy books and gives them away to Net users who are interested.

It is probably one of the most loosely organized book clubs there is, in the sense that there are no rules involved. Anybody who is interested can join. But there isn't a regular place online, be it a forum or a chat group, where people can join in discussions.

In principle though, people who get the books are supposed to write a short comment or some thoughts to share with others. But Chen doesn't actually keep track of this and there is no way of making sure that the users who receive the book actually read it. Nor does he see a need for such supervision. "We are all adults here. What's the point of pushing them every day?" he said. "At least some would have read the books and that's enough."

While nothing is obligatory, some Net users do actually write short reviews or comment on the book's introductory page on Douban, mentioning that they are writing the review for the book club activity.

Between July 2012 and last November, the book club event was held 17 times and each month Chen sends books to over a dozen people. The books he selects focus on China's social transformation, the building of a civil society, or history after 1949.

The list of books he selects indicates the message he is trying to send. The books are written by renowned Chinese scholars such as Liu Yu, a political science professor at Tsinghua University, Zhang Qianfan, a law professor who specializes in the Constitution from Peking University, and Gao Hua, the late history professor from Nanjing University.

There are books on history, law and democracy. The titles of the books include Democracy is a Modern Lifestyle, and Lessons from the Democratic Transformation of Taiwan.

None of the books were banned though, and are all published in the mainland.

Chen doesn't seem to give too much thought about what he is doing, and yet it seems a natural thing for him to do. "I was inspired when I listened to or read those scholars, and I feel others could benefit from them too," he said.

A selection of books recommended by Law Stars Club: