Ever more thirsty

People look over the Yellow River in Yongji, North China's Shanxi Province on December 29, 2013. Photo: CFP

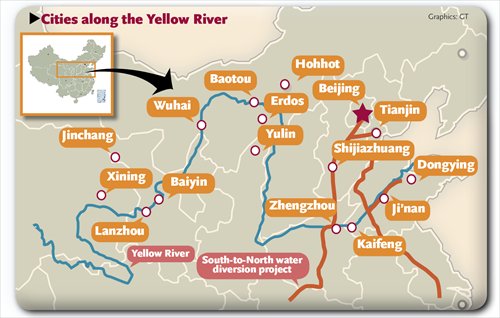

Cities along the Yellow River Graphics: GT

In recent years, it has become normal for officials from cities along the Yellow River to pay frequent visits to the Yellow River Conservancy Commission (YRCC) in Zhengzhou, Central China's Henan Province.

Regular visitors to the YRCC include leaders from Ordos, a city in North China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region that boasts vast coal reserves and has ambitious plans for coal-to-chemical projects. There have also been visits from leaders of nickel-producing Jinchang city and nonferrous metals center Baiyin city, both in Northwest China's Gansu Province.

What they have in common is that they had all exhausted their quota of Yellow River water usage and were all asking for more, for the sake of local development.

The YRCC is a supervisory body under the Ministry of Water Resources. It governs the exploitation of the river and the quotas for water usage.

"The water security issue is a long-term, nationwide concern and it is getting more and more serious," Lin Boqiang, director of the China Center for Energy Economics Research at Xiamen University, told the Global Times Thursday.

Although the Yellow River is the second-largest river in China, its natural runoff has shrunk from 58 billion cubic meters two decades ago to 53.5 billion cubic meters in recent years, according to a China Business News (CBN) report on Wednesday.

The utilization rate for water from the Yellow River is 70 percent, while the internationally accepted warning level is only 40 percent, CBN reported.

Need for water

"While all the provinces along the Yellow River face water shortages, the issue is a real bottleneck for the development of those that are more reliant on energy," Lin said.

Exploitation projects for coal, oil, and natural gas and the generation of electricity all need huge amounts of water, Lin noted.

"One water guzzler in particular is the emerging coal-to-chemical sector," Deng Ping, a climate and energy campaigner with Greenpeace, told the Global Times on Thursday.

Six to 10 tons of water is consumed to get one ton of end product in the coal-to-chemical production process, Deng said, citing a 2012 Greenpeace report on water resources and the development of coal plants.

Areas mulling coal-to-chemical projects include Shaanxi Province and Inner Mongolia and Ningxia Hui autonomous regions, with planned annual output of tens of thousands of tons, CBN reported.

However, there is no more quotas that can be allocated to these water-thirsty provinces.

Relief from the south

After around half a century of debate, China began construction of the South-to-North water diversion project in December 2002.

The ambitious project aims to allow the water-deficient northern regions to "borrow" billions of tons of water from the southern regions.

As the project has the potential capacity to divert 14 billion cubic meters of water to northern China per year, Inner Mongolia and Northwest China's Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region have expressed a desire to get the 2 billion cubic meters of Yellow River water per year that are currently allocated for North China's Hebei Province and Tianjin Municipality, CBN reported.

"The cost of water from the project far exceeds that of water from the Yellow River," Shen Dajun, a professor at Renmin University of China and an expert on water issues, told the Global Times on Friday, while acknowledging that the project will lift some of the pressure on water supply in northern China.

The actual cost for water from the central route of the project has reached 8-10 yuan ($1.31-$1.63) per cubic meter, according to an article by Qiu Baoxing, vice minister of housing and urban-rural development, in Water & Wastewater Engineering Magazine on February 19.

In comparison, the price of water from the Yellow River is less than 1 yuan per cubic meter, Shen noted.

"The project will help but it won't solve the problem, partly because water resources in the southern regions are not as plentiful as we thought," Lin said.

We want more

Lacking an immediate remedy for additional supply, provinces have been turning to a new mechanism called the "water rights transfer program," which allows them to take some of the water quota for agricultural use and put it toward industrial use instead.

In return, industrial water users pay the agricultural sector to help with development and promotion of water-saving techniques and building modern irrigation facilities.

Agriculture consumes 70 to 80 percent of the water allocated to each province, while industry consumes 10 to 20 percent and cities and residents use another 5 percent, according to Shen.

However, things are not that simple.

"Only a tiny portion of water allocated to the agricultural sector is actually consumed by crops. Most of the water will find its way back into the ecosystem, primarily as a recharge for underground water," Deng said.

The industrial sector, however, can literally consume water, whether it evaporates or is absorbed during the process, Deng noted.

Shen also expressed doubts about the effectiveness of new water-saving technology.

"The traditional water-saving measures are all already in place. Irrigation methods have already been upgraded and all the industrial facilities are now designed with water-saving measures in line with modern-day practices," Shen said.

Any new water-saving technology will have to be revolutionary to have a significant effect, Shen said.

Lin said it was time to address the issue from the consumption side, rather than the supply side.

"In the past, we racked our brains to find ways to gain extra water supply for a newly constructed power plant," Lin said. "We should now rack our brains to invent more economical ways of using a given or even a decreasing water supply quota for our new power plant."

Meanwhile, the landscape is changing.

In Ningxia, where there are irrigation ditches dating back 2,000 years, testifying to the region's time-honored agricultural traditions, the area devoted to rice paddy fields has shrunk by one-fifth in the last 60 years. The area is now being used for wheat, which needs less water, CBN reported.

In Inner Mongolia's Hetao irrigation area, farmers have been gradually replacing the traditional crop of wheat with corn, which is less drought-sensitive.