Court acceptance of wartime slavery lawsuit provides hope for survivors

A total of 6,830 pairs of cloth shoes are laid at the square outside the Memorial Hall for the victims of the Nanjing Massacre by Japanese invaders in Nanjing on August 14, 2010, to pay tribute to the Chinese victims of forced labor who died in Japan. Photo: CFP

Zhang Shijie, 88, gave a sigh of relief when his son Zhang Yang told him a Beijing court had accepted a lawsuit against two Japanese firms who forced him and another 37 Chinese people to work as free labor during World War II. "I finally have something to look forward to," he said.

Like other Chinese forced laborers, Zhang's biggest wish has been to receive compensation from the Japanese companies that made him a slave. But despite long-held grievances over the issue and the high profiles of some of the companies involved, this is believed to be the first time a Chinese court has accepted a case of this kind.

"They treated us like animals. We filed the lawsuit not for money, but for justice," Zhang told the Global Times.

Official documents from Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan showed that a total of 38,953 Chinese people, aged from 11 to 78, were captured by the Japanese army and forced to work in at least 35 companies and 135 workplaces from April 1943 to May 1945.

The two companies targeted in the lawsuit the Beijing No 1 Intermediate People's Court recently accepted are Japan's Mitsubishi Materials Corporation and the Nippon Coke and Engineering Company, formerly known as Mitsui Mining. The two are alleged to have held 9,415 Chinese workers, with 1,745 dying in Japan.

According to the indictment, two survivors and 35 people whose relatives were forced laborers are demanding one million yuan ($160,600) in compensation for each worker, as well as apologies printed in Chinese and Japanese newspapers.

"History cannot be forgotten. The blood, tears and wounds cannot be erased," Kang Jian, a Beijing lawyer who helped filed the case, told the Global Times. Kang has spent almost 20 years finding and visiting the victims of forced labor, collecting evidence and filing lawsuits in Japan and China.

Relative of victims of forced labor head to the Beijing No 1 Intermediate People's Court on February 26, to file a lawsuit against Japanese companies in an attempt to seek compensation and an apology for the victims. Photo: IC

Unflagging determination

Similar cases have been on the books for decades but were almost always rejected by Japanese courts. "We never gave up seeking compensation," Kang said.

"The problem is that Japanese courts said the Chinese government abandoned its right to make such claims when both countries normalized their relationships, and some local courts even refused to accept the cases."

Despite a court in Tokyo ruling that the Japanese government should pay 20 million yen ($195,560) in compensation to relatives of a deceased forced laborer Liu Lianren in July 2001, Japan's Supreme Court rejected the verdict.

On more than 15 occasions, Kang, victims and descendants of victims have attempted to file appeals with Japanese courts, but all have been rejected.

Analysts say the Japanese government has rejected these appeals because it is trying to shirk its responsibilities by redefining the terms of their previous agreements.

"Obviously, Japan is trying to change the terms of the Japan-China joint statement," Yang Ling, an expert on Japanese issues from Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, told the Global Times.

Although the Chinese government forfeited the right to make claims and compensation according to the 1972 Japan-China joint statement, individual citizens are not under any such restriction, Yang noted.

On the day after the Chinese court accepted the lawsuit, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Hong Lei said Japan should seriously address issues of forced labor during its war of aggression.

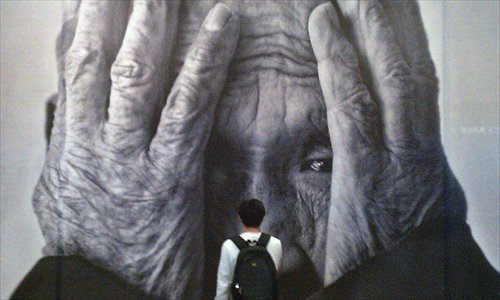

A visitor stops to look at a photograph of a survivor of World War II forced labor at an exhibition at the Shandong Museum on December 11, 2011. Photo: CFP

Tormented by the past

"My father cannot remember many things because of his age, but he said he never forgot being captured to Japan. He remembers how, when and where they were forced him to work," said Zhang Yang, Zhang Shijie's son. Zhang Yang has been living with his father to take care of him. "He said he felt humiliated that they had been treated like animals."

Born in Wuqiang county, Hebei Province, in 1925, Zhang Shijie had a restless childhood. In 1943 he was captured by Japanese soldiers. At that time, he was working undercover for Chinese Communist troops, secretly collecting information about the enemy.

Zhang said that on June 10, 1944, a day that was forever etched in his mind, he and about 60 other Chinese people were whipped and driven onto a truck. There, they were transported to a prison in Hengshui, Hebei Province. In the prison, Zhang and other 17 men were jammed into a 10-square-meter room. To ensure they couldn't run away, they were chained together with iron rings around their necks.

After 10 days in Hengshui prison, Zhang, along with 90 other forced laborers was sent to the Hengshui railway station, and from there they arrived in a concentration camp in Tanggu. During the trip they were forced to stay in an airtight train carriage for over 14 hours, without food or water at the height of summer.

From Tanggu, Zhang and other Chinese forced laborers boarded a boat and were sent to Japan. Cui Guangting also left China from Tanggu. Born in 1924 in Hebei, Cui was captured to work for Mitsubishi in October 1944.

At that time, Cui worked as a correspondent in the Chinese government as it was trying to repel the Japanese invasion. In May, when he returned to his home, his identity was exposed and he was captured by Japanese soldiers and thrown into prison.

On July 7, 1944, Zhang and Cui were driven onto a boat headed for Japan, along with some 160 people from the concentration camp. They were asked to stay in a train compartment filled with coal. They were not allowed to leave the compartment for the entire 13-day voyage.

Zhang clearly remembered that a person from Hebei jumped into the sea because he was worried about his family.

Torment started from the moment they arrived in Japan, Kang said. "The ripped off their clothes and whipped them into a dark house while they were naked. Then they sprayed disinfectant all over their bodies, even into their faces," Kang told the Global Times.

"They had to work for over 10 hours a day and were fed musty steamed buns and pickles once a day. They were not allowed to drink water while working in order to save time. And they would be beaten heavily by the guards if they picked up rotten leaves or food from rubbish bins to feed themselves," Kang said.

Sometimes, they had to steal food from the mouths of rats, Kang added.

Two days after they arrived, Zhang was asked to work in the coal mine. The Japanese guards also prohibited them from calling each other using names. Instead they were assigned numbers: Zhang Shijie's number was 7744, a number he would never forget.

Every morning at 5 am, Zhang and other forced laborers were gathered and sent to work in the pit. Each day they had five steamed buns, three for breakfast and two for lunch. However, on the first several days, their food was eaten by big rats.

Kang said they were often beaten if they took rests, forgot their assigned numbers or didn't speak in Japanese. Long-work hours, over 10 hours per day and little food left them with all kinds of diseases, ranging from stomach illnesses to lung diseases and dermatitis. "None of them were healthy after they had been tortured," Kang said.

Zhang was diagnosed with serious stomach diseases, but compared to the physical problems, the mental trauma was much worse.

"Even now, many victims will suddenly raise their voices and become agitated when they recall their story of they were forced to work in Japan. They cannot withhold their anger," Kang told the Global Times. "They have hatred in their hearts."

Fading away

Zhang Shijie's face contorts with rage when he recalls his experiences of that time. His frustration is compounded by the rejections by the Japanese courts and the incessant traveling to seek justice.

In recent years, with donations from Japanese nationals and some local NGOs, Kang has led groups of survivors to file lawsuits in Japan.

They had to overcome all kinds of difficulties. Elderly, frail survivors had to be taken care of. Sometimes they were incapable of providing case details if they fell ill. Unable to speak Japanese, the survivors felt desperate when interrogated by the defendant's lawyers.

Many of the survivors have since passed away. "There were 200 survivors when we first started to find victims of the Japanese labor forces from 1996-2000, but now we have only two survivors," Kang told the Global Times.

Kang said that the acceptance of the case by a Chinese court provides encouragement to victims, particularly given the fact all attempts had failed in Japanese courts.

But several Japanese media outlets expressed concerns it would prompt similar lawsuits and worsen the already dismal ties between the two countries.