Hidden among the Himalayas

Ji Wenzheng displays pictures of Lhoba and Monba people he collected. Photo: Jin Jianyu/GT

Climbing the Himalayas and venturing between the craggy cliffs that line Tibet's raging Yarlung Tsangbo River are mighty achievements in their own right. But 81-year-old Ji Wenzheng has done both scores of times, in an effort to record the cultural legacy of an isolated county in southeastern Tibet.

He is among the few people to earn the trust of the Lhoba and Monba people, two ethnic minorities in Medog, quite possibly the most isolated area of the country which only gained highway access in 2013.

"You need to climb over the Himalayas at noon or at least before night falls. Don't talk loudly when hiking together with the Lhoba or Monba guides, as they believe speaking loudly would scare away the mountain gods and bring in heavy snow or rain," Ji said.

He has hundreds of nuggets of advice like this. In the past 60 years, in an effort to record their cultures, Ji has written down nearly 5 million words in diaries, books and articles, snapped around 500 photos and recorded 168 hours of folk songs and stories in 86 tapes.

"There is no written language for the two isolated groups. Their unique slash-and-burn culture will gradually vanish if we don't record or protect it in time," Ji told the Global Times.

Ji was also the first person who advised the government to identify the two tribes as two distinct ethnic minorities in his 11 detailed reports based on his nine years' research since 1955. In 1964, the central government recognized the Monba as an ethnic minority and Lhoba as another a year later.

"It meant the two groups could enjoy preferential material, financial and educational support from the central government," said Ji.

No pain, no gain

Born in a Henan family in 1933, Ji was dispatched by the People's Liberation Army to Medog with another colleague on August 24, 1954. Their mission was to learn more about the locals in the nation's border area and figure out what they needed.

Climbing mountains rising over 4,000 meters above sea level of the Himalayas was the main way in and out of Medog. Dubbed the "secret lotus," the county is also located on the major sharp curve of the Yarlung Tsangbo River.

"Enduring the acute altitude sickness on the Himalayas was just the beginning," said Ji, who has climbed the mountain 28 times. The roads to isolated villages are also dangerous, but ultimately necessary to traverse. In many of these villages, locals lack the farming tools they need, and even lack daily necessities like salt.

Ji said they had to traverse the steep mountains barefoot, crawl along the swinging ivy bridges or slide down rope cables stretching hundreds of meters over deep valleys to hand out badly needed tools or offer medical treatment to the locals.

As the county is located in a semitropical area, Ji also had to fight the leeches which were drawn toward the open wounds caused by the thorns on the rough paths to the 16 villages he visited.

"I once found 13 leeches on my body, eight of which were still sucking my blood, when I rested on a mountain after elbowing my way out of the thorns."

Ji also had to adapt to local superstitions, such as witches casting spells to drive away illnesses, or archaic practices such as using knots in ropes to keep records.

In January 1955, Ji was invited by a Lhoba tribal leader to eat stewed mice, their best food for guests, during their New Year dinner, as thanks for his contributions to their tribe.

"I felt a bit nauseous, but I managed to persuade myself to swallow the meat. The move won me praise from the tribe's family."

Ji said all the pains he endured were because he felt the mutual trust he earned with the locals was worth it. It paved the way for his collection of the distinct folk culture that fascinated him.

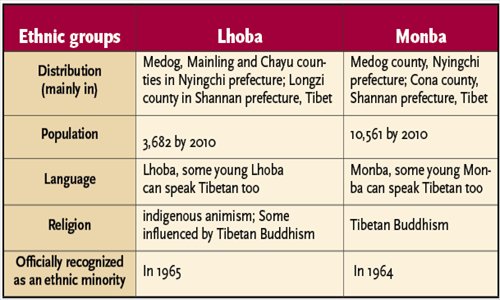

Graphic: GT

Half-century effort

To better understand the local cultures, Ji first spent eight months learning to speak and understand the Lhoba and Monba languages.

As there is no written script, the locals mainly passed down their folk tales, songs and proverbs orally to their descendants. Ji felt it was of great necessity to help them record their culture.

"Folk literature is an intangible cultural legacy. A song or a story may provide the clues to a stretch of the ethnic group's history," said Ji.

During his 16-year stay in Medog till 1970, Ji talked with residents from every village he visited. He recorded 840,000 words of their songs, customs, proverbs and fairy tales and wrote down 560,000 words.

Later, Ji invited a total of 15 Lhoba and Monba artists to visit him at his house on a number of occasions during his 18-year stay in Lhasa.

After retiring in 1988, Ji revisited the county three times to extend his research. The last time he climbed over the Himalayas was in 1996 when he was 64 years old.

"My husband spent all his spare time and savings on these two peoples," Ji's wife Kuang Xianhua, now 77 years old, who only sporadically saw her husband during his 16-year stay in Medog, told the Global Times.

Dreams to fulfill

After years of assistance to the two peoples, now many Lhoba and Monba people have moved into more modern homes.

It's not rare to see motorcycles, tricycles and even cars running across suspension bridges in the county. Schools are available for children and highways to the outside world are accessible too.

But Ji feels more has to be done to preserve and promote their traditional culture. Ji has already published 14 books, and plans to release seven more.

Ji has sorted out contents for another seven books about the local ballads, proverbs and photos taken in the 1950s.

"Collecting these materials was like fishing for a needle in a haystack. I hope they can be made public soon," said Ji.

Newspaper headline: One man’s quest to preserve the identities of obscure ethnic minorities