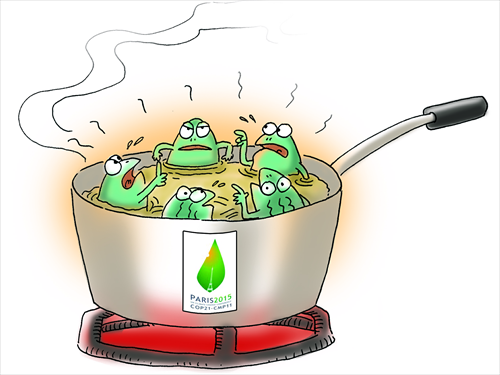

Geopolitics may frustrate efforts at change in Paris climate summit

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

The Copenhagen summit in 2009 saw the emergence of the BASIC group of countries (Brazil, South Africa, India and China), but also a glimmer of the G2, which some refer to as the "invisible group," comprising the US and China. These players sealed the fate of the decisive summit in 2009 and now in 2015, when the international community is yet again all set to clinch the post-2020 agreement, the dynamics between them have changed again.

The joint communiqué on climate change by China and the US in 2014 during US President Barack Obama's visit to China, followed by the joint presidential statement in 2015 during Chinese President Xi Jinping's visit to the US, has undeniably boosted expectations that the Paris Summit would succeed in reaching an ambitious agreement. The two powers have been blamed for the repeated failure of the climate change negotiations in the past.

Geopolitically, the steps taken by the US and China raised hopes in terms of emissions reduction targets from the other major emitters, both among the developed, such as Australia and Canada, and developing countries, such as India and Brazil.

India and Brazil seem to have lived up to expectations, with the former agreeing to reduce the emissions intensity of its GDP by 33-35 percent by 2030 below 2005 levels and the latter becoming the first developing country to commit to an absolute reduction of emissions; but countries such as Australia and Canada are still sticking to low-hanging fruit.

Whether or not these new developments can be termed indicators of the re-emergence of G2, the united stance put up by the BASIC nations at the Copenhagen summit is no longer intact. The four countries differ on many issues including peak emissions, reductions in absolute emissions, and reporting standards.

Although in principle they agree that the onus lies with the industrialized bloc to provide financial resources to the developing and least developed countries, China has already pledged to establish a China South-South Climate Cooperation Fund to assist other developing countries to tackle climate change.

While China and Brazil joined hands with the US in making "landmark" joint announcements with an eye on the future climate regime, India chose to keep things at a low key this year. It is not willing to declare any emissions reduction target nor is it willing to discuss a peak year for emissions.

However, in its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC), it has announced ambitious targets in not only reducing emissions intensity but also forestry and renewable energy. Moreover, its position has been more or less acknowledged by countries such as the US, Germany, and France among others, that have entered into several bilateral agreements that cumulatively add to India's long-term climate commitments.

The EU was one of the first to announce its INDC (centered on mitigation) but its non-committal approach toward technology transfer, adaptation, loss-and-damage mechanisms and finances has not gone down well with many in the developing world. With its disclosure of expectation of contributions from the emerging economies to the UN Green Climate Fund (GCF) owing to the change in the geopolitical realities, the fault lines are apparent.

At the same time, the EU has also managed to attain China's endorsement for a legally binding bottom-up INDC process in a joint communiqué issued by the two parties in June 2015.

Most importantly, the Alliance of Small Island States, Small Island Developing States and the Least Developed Countries, which are most affected by climate change, are likely to act as pressure groups at the Paris summit - trying to get the best out of the major powers, starting from their demand to limit the temperature rise to 1.5°C rather than 2°C to more financial-cum-technological resources for adaptation and mitigation.

What remains to be seen is how these geopolitical moves and equations would shape the future climate order.

The author is a Project Associate, Manipal Advanced Research Group, Manipal University, Karnataka, India. dhanasreej@gmail.com