HOME >> OP-ED

Sticking together can work for minorities

By Rong Xiaoqing Source:Global Times Published: 2016-4-21 22:33:01

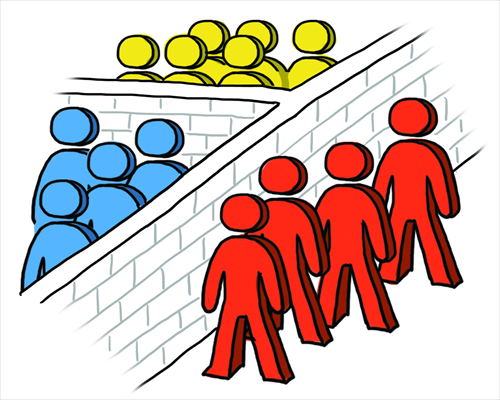

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

A young friend who came to the US to study to be a teacher recently complained to me about her internship experience at a public school in the Bronx. "Almost every student in the entire school is either black or Hispanic. And the teacher's work is not really teaching but to keep these kids from fighting or wrecking the classroom," she said. "The education system in this country is much worse than I thought."

This is not a surprise to any New Yorker. An analysis conducted by the education news website Chalkbeat in January found only two of the city's schools have student bodies as diverse as the city's demography. And a study released in December by the Center for New York City Affairs at the New School found the majority of the public primary schools in the city have more than 90 percent minority students.

The findings align with some previous studies, including one released by the Los Angeles' Civil Rights Project at the University of California in 2014 that found that in 2009 schools in New York were the most segregated in the country.

The segregation in schools is clearly a byproduct of the segregated population in the city.

In the Disney animated movie Zootopia, the fictional dreamworld where the predators and the prey co-exist is divided into six different districts from The Rain Forest to Sahara Square to suit the different needs of various groups of citizens. In the real world, these districts are called Chinatown, Little Italy, Korea Town and other names that recognize the dominance of an area by one single racial group.

Even in the most diverse city in the world, people still tend to stay in their own territories with their own people to get the sense of safety and comfort.

It's of course imperfect for the idealists. Recently, efforts to desegregate are picking up momentum again. New York City's Department of Education has been considering whether to launch a pilot program in some schools to increase diversity by changing the admissions formula. For example, one program plans to require students to provide information about their family income, parents' education level, and housing situation and to match underprivileged children, most likely black and Hispanic, with schools that don't have many such students based on a set of algorithms.

And the city's ambitious plan to build and preserve 200,000 affordable housing units in ten years is considered as an opportunity to break some of the segregation between neighborhoods.

Wealthier neighborhoods undoubtedly have a lot of benefits. Experimental programs in other cities have shown that resettling poorer people into more affluent neighborhoods with the help of public subsidies can help low income minority families to break the vicious cycle formed in their old neighborhoods and lead to greater upward mobility.

But what minority people lose in this idealistic version of "the melting pot" is also striking. The idealists may not realize that in a diverse city, segregation can not only be a voluntary choice for many of its dwellers, it may also be the only way for some of them to survive and thrive.

One example is the recent victory of the Chinese community in getting the Lunar New Year listed as a school holiday in the city. One of the powerful arguments elected officials in the Asian neighborhoods put in front of the city was that in neighborhoods like Chinatown, where more than 90 percent students are Asian, the classrooms were already largely empty on the Lunar New Year anyway.

Great Neck on Long Island in March approved a similar proposal filed by Chinese and Koreans. The promptness of the approval was a pleasant surprise even to those who drafted the proposal. But the reason is clear - among the 3,400 students in that district, 34 percent are Asian. And in some schools more than half of the students are Asian.

In New York, Chinese politicians from Congresswoman Grace Meng to Council members Peter Koo and Margaret Chin were all elected in neighborhoods where the Chinese make up a big voting bloc.

In a perfect world, elected officials of any racial background should be able to serve all people equally. But in the imperfect real world our knowledge and understanding of racial groups other than our own are all limited. And constituents who are not able to elect one of their own to be their representative are often destined to be underserved.

The political system has decided that segregation, ironically, is the best way for minority people to fight for their rights.

The author is a New York-based journalist. rong_xiaoqing@hotmail.com

Posted in: Columnists, Viewpoint, Rong Xiaoqing