Exam sparks debate on oversight

China's PE and VC funds have grown increasingly important in recent years as sources of funding for small and medium-sized enterprises that have trouble qualifying for bank loans. As PE and VC funds have developed fast, the industry has received both greater government support and scrutiny as problems such as illegal fundraising have emerged. Following a recent exam controversy, a debate has surfaced about how to best regulate this rapidly developing industry in China. Experts suggested a moderate approach.

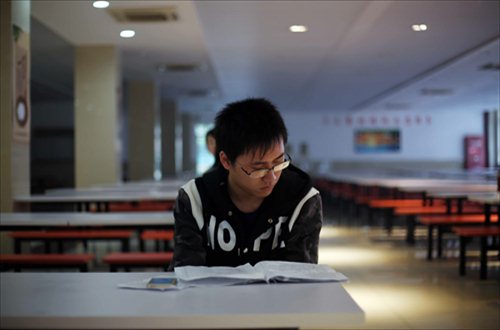

An examinee prepares for the qualification exam for fund practitioners on April 23 in Shanghai. More than 300,000 examinees sat this year's exam, including bank workers, PE and VC employees as well as students. Data showed that 71.15 percent and 28.95 percent of all test-takers passed the first and second parts of the exam, respectively. Photo: IC

In China, even a test can cause controversy.

A qualification exam for fund managers on April 23 has sparked a debate about how the government should regulate China's booming private equity (PE) and venture capital (VC) funds industry.

The exam was initially designed for fund managers, the type of people who make their money trading stocks, bonds and derivatives on the secondary market.

So, the Asset Management Association of China (AMAC), which runs the exam, got into trouble with some finance professionals when in February it required at least two executives to sit the exam, even though their companies weren't involved in trading securities.

Instead, the executives worked for what is known as non-securities private funds, a group that includes PE and VC funds. These funds invest their money directly into companies via the so-called primary market and generally don't trade public securities.

Facing the possibility that some of their brethren might fail the test - and have their licenses revoked - PE executives responded by complaining on social media that they were being forced to take an exam that didn't actually test them on what they did for a living.

"The content of the exam is heavily focused on the secondary market, not suitable for practitioners in the primary market," said Chen Wei, a senior consultant with Beijing-based investment consulting firm ChinaVenture.

As it turned out, the PE managers didn't do particularly well. About half of them failed the second part of the exam, the Beijing Times newspaper reported on Thursday.

In regard to the complaints, AMAC said it was considering the issue, according to Li Weiqun, secretary-general of China Association of Private Equity (CAPE), an industry union in Beijing, which met with AMAC to discuss the issue on April 24.

The exam controversy may not be all that important to anyone outside this corner of the financial world.

But it does beg the question: If exams aren't the way to regulate China's PE and VC funds, then what is?

The question is significant if one considers the industry's size and the increasingly important role it plays in funding companies in the private sector. By the end of March, China's registered PE funds had 5.7 trillion yuan ($880.65 billion) in assets under management, including 94 funds each with more than 10 billion yuan in assets, according to AMAC data.

"PE and VC, as direct financing channels for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), is a beneficial supplement to bank credit, which SMEs have a hard time getting," Chen told the Global Times on Friday.

In a sign of the industry's importance, China's central and local governments have also taken special interest in PE and VC funds, launching many policies to support their development.

Beyond bank loans

In terms of funding, China's VC and PE funds have outpaced the rest of the financial system.

Total social financing, a broad measure of funding from the financial system, grew 12.4 percent year-on-year to 138 trillion yuan in 2015. Meanwhile, total investment disclosed by PE funds jumped 30.6 percent to $48.35 billion in 2015, according to a report released by ChinaVenture on April 26. For VC funds in 2015, the amount skyrocketed 137.8 percent to $36.95 billion.

And that's just the tip of the iceberg. In developed countries, PE funds accounted for 4-5 percent of a country's GDP in 2015, the China Times reported in November 2015.

In China, the proportion was 0.2 percent in 2014, according to the Shanghai Securities News.

"PE and VC have a lot more room to grow in China," Li told the Global Times on Friday.

Li also pointed out that PE and VC also provide enormous funding for the early-stage start-ups, helping increase local tax revenue and foster employment.

Emerging problems

Some believe the exam signaled that the government has some changes in store for PE and VC funds.

"The test was also a sign that the regulator is tightening supervision over the industry," said Lin Yixiang, chairman of Beijing-headquartered TX Investment Consulting Co.

Li from the CAPE acknowledged that there are problems and hidden dangers in the industry, and called for changes in government supervision. In his view, one major problem is the abuse of industry licenses.

"Some PE funds make use of the licenses to solicit funds from the public, essentially engaging in illegal fundraising," he said.

PE and VC funds are not allowed to raise money from the general public. The regulations exist to prevent individual investors from getting exposed to risky projects that they could not afford to lose.

In one case, an individual investor spent 5 million yuan on a fund product from the Beijing-based PE firm Aoxin Fund, the Beijing Evening News reported in June 2015.

Aoxin raised the money to invest in an industrial park project in Central China's Hubei Province, but the project never paid off. Consequently, the fund refused to repay the investor the principal and interest on the product, even though it initially promised high returns.

Although the project was legitimate, it still failed, costing the one investor 5 million yuan. The Beijing Evening News report quoted a lawyer who said Aoxin's action constituted illegal fundraising.

Embezzlement has emerged as another problem.

So far this year, the AMAC has added 21 PE funds to its list of institutions with which it has "lost contact." Companies can make this list when the AMAC can't reach them by telephone, mobile phone, e-mail or other means over a specific period.

In some cases, a company makes the list when one or more managers abscond with investor money, Li said.

In July 2014, Jiang Tao, legal representative of PE firm Haicang Capital, disappeared with at least 500 million yuan belonging to more than 300 individuals, the 21st Century Business Herald reported on July 29, 2014.

His present whereabouts has not been disclosed by the media.

Regulation debate

Although problems exist in the industry, experts do not advocate a "one-size-fits-all" approach.

"That will cause the industry to shrink, which will hurt the government push for entrepreneurship and innovation, both of which rely on PE and VC funding," Li said. Li also called for "moderate supervision." He recommended against launching more restrictive laws and regulations for PE and VC funds.

"PE and VC funds developed rapidly in the US and Israel partially due to the loose policy environments."

He advocated for regime marked by self-regulation and supplemented by government supervision, noting this is common in Western capital markets.

Chen agreed with Li, but added that self-regulation should be grounded in a sound legal system.

Rather than intervene directly, authorities ought to improve the laws that relate to the PE and VC industries, and supervise PE and VC funds to do business under this legal framework, both Li and Chen said.

Newspaper headline: China’s PE, VC funds test limits of regulation