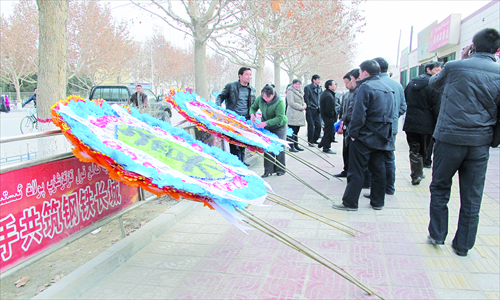

Yecheng after the attack

Chen Bixia, 42, has been lying in bed weeping for days. She has barely eaten or slept since she witnessed her husband being murdered by terrorists in front of their shop 10 days ago in Yecheng county near the city of Kashi, in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

Whenever she drifts off, the nightmare she experienced shocks her awake. It takes her half an hour to collect herself for an interview with the Global Times.

Through tears she recalls how her husband was on his way to the bank and had just left their shop when he was brutally attacked. Panic stricken she hid under a table as the terrorists continued their killing spree throughout the market area.

Terrorists killed 13 people on February 28 and have again shaken Uyghur and Han residents in communities along the ancient Silk Road that are about 250 kilometers from the border with Pakistan.

Some nine attackers armed with axes and blades attacked store owners and shoppers in the market where most of the shops are owned by Han. Police shot dead seven terrorists and captured two, said a government statement which didn't identify the ethnicity of the victims or the attackers.

Days after the bloodletting, most shops in the market remained closed but people gathered to share their experiences and losses and try to comfort each other.

"Yecheng county has been in peace for years but now we are scared and don't know what to do," said Cheng Jizhong who witnessed the killing from his corner store.

Yecheng was founded at an oasis centuries ago and is now home to 500,000 people. Only 6 percent are Han. Despite the killings that have occurred in Xinjiang in recent years, few thought terrorists would attack here.

Down the road in Kashi, formerly known as Kashgar, terrorists rampaged for two days last July, killing 14 people and injuring 40. Most were Han.

As soon as the February terrorist attack occurred, heavily armed police set up roadblocks and checked vehicles going in and out of Yecheng.

Fearful Han residents also took familiar and practiced precautions. They sent messages to relatives assuring them they were safe and warned others not to leave their homes. Shop owners in another market closed their stores as soon as they got word of the attack fearing they might be next.

Even far away in the region's capital, Urumqi, where news of the attack in Yecheng hadn't yet become common knowledge, worried residents noticed the stepped-up police patrols around their city.

"Fear - this is what exactly what the terrorists want," Turgunjan Tursun, an associate researcher with the Institute of Sociology at the Xinjiang Academy of Social Sciences, told the Global Times.

Ever since Urumqi was hit by deadly riots in 2009, which left nearly 200 people dead, ordinary people have become terrorists' target, he said.

"Instead of attacking police, government officials and religious people, terrorists now target ordinary people. They are easier to attack, creating more fear, and garnering more international attention," said Tursun.

The sole purpose of the terrorists, said Tursun, is further drive a wedge between Han and Uyghur people.

The terrorists' motives appear to be working with Chen who has grown hateful while she mourns the loss of her husband. She didn't say if she would restrain her three children, who are aged between 16 and 20, from seeking revenge when they return to Yecheng.

"It is hard to estimate how much damage the riots have done to ethnic relations and how much time will be needed to heal the wounds," said Tursun.

Terrorist training

Yecheng has not been immune to encounters with terrorists. When a terrorist training base was discovered in the country the extremists were forced to flee to Pakistan.

Since 1990 terrorists of the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) have been reported setting up dozens of training bases in communities around Kashi. According to the police, there were three training sessions in Yecheng, where some 60 terrorists were taught religious extremism and terrorist tactics.

A government official, who spoke to the Global Times on condition of anonymity, said the terrorist trainers reach out to undereducated local farmers who can more easily be converted to religious extremists.

"There is no doubt that the rapid economic development taking place in Xinjiang has brought significant change, but many Uyghurs see themselves as a minority in their own land," the official said.

"They might harbor anti-Han sentiment but that doesn't turn them into terrorists. It's those extremists that we are afraid of," he said.

"We have intercepted some religious textbooks which might make people think of killing," the official said.

Underground religious activism

In early February, the regional government has again launched a campaign to stamp out rising religious extremism.

A public lecture campaign will be carried out throughout the year in every village and residential community. At the lectures, officials will elaborate on the government's religious policies and reiterate the dangers of being caught participating in illegal religious activities. Religious leaders at the lectures will discuss proper dress codes and patriotism, and call for peaceful coexistence, according to the Xinhua News Agency.

Many Uyghurs, however, have told the Global Times the lectures are not only patronizing, they don't get to the heart of the issues that disturb them.

They say a broad ban on independent study of Islam is driving many Uyghurs underground and forcing them into a counter culture that may drive them into extremism.

According to State Council statistics there are 23,753 mosques authorized to hold religious services and 26,500 approved Islamic clerics in Xinjiang, which has a population of more than 20 million people: 46 percent are Uyghur and 40 percent are Han.

Local experts said the State-sponsored Islamic education system allows the government to control which teachers are hired, which students are selected, and the content of their courses.

To offer private classes, a cleric must seek the permission of the government and detail the number and names of his students. Permission is not easily obtained, say Muslims wanting private instruction.

Only one Islamic college in Xinjiang teaches Uyghurs in their native language. Each year about 1,000 students apply to get in but only 60 are accepted at the all-male school. After five years of studying ethnic policies, the Arabic language and religion, graduates can seek to become a cleric at a mosque.

Uyghur Muslims believe the translations of the Koran are not good alternatives to reading and understanding the Arabic version. Some Uyghurs have learned how to recite the Koran in Arabic but many don't understand what they are actually reading.

With the help of a private instructor 30-year-old Aike is studying the Arabic version of the Koran even though he can't read or speak Arabic. This kind of private tutoring is only available by invitation from a friend of friend.

The government considers Aike's private lecture to be "illegal religious activism." "But there is no other way for us to learn how to read the Koran. They are not teaching us in schools or the mosques, so I have to take the risk," Aike said.

Religious extremism blamed

"The Koran requires you to wash hands before dinner, but you need an instructor to help you understand the deeper significance and formality of these practices," he told the Global Times.

Speaking at the "Two Sessions" in Beijing on Monday, Nur Bekri, chairman of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, said he supports cracking down on illegal religious activities such as underground lectures.

"Illegal religious activities inevitably cause religion fever. Religion fever inevitably causes religious extremism and religious extremism inevitably causes violent attacks," he said,

In recent years, a number of Chinese Muslims have completed studies abroad in Islamic countries, such as Egypt, and have returned home to become authorized teachers at mosques and other places.

According to the latest statistics, violent crimes in Xinjiang declined 4.47 percent in 2011 from the previous year. The total number of crimes was not revealed.

Li Wei, a counter-terrorism expert with the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, told the Global Times that the Xinjiang government is taking every precaution to prevent terrorist attacks.

"Some attacks might be unavoidable, but the regional government has everything under control," he said.

Back in Yecheng county a woman sells tofu in the market where the terrorists struck on February 28. She's the only one who has dared to reopen her business and both Uyghur and Han residents drop by for a block of her fresh tofu.

Asked if she is frightened, she nods. "But life has to continue, right?" she answers.