Political pop icon

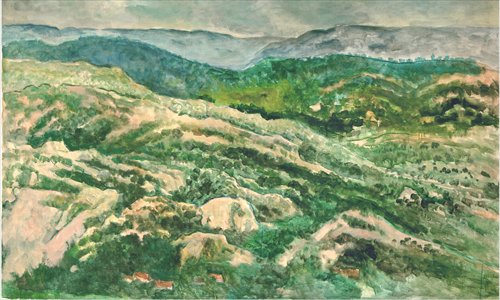

One abstract from Yimeng Mountain series Photo: Courtesy of Yu Youhan

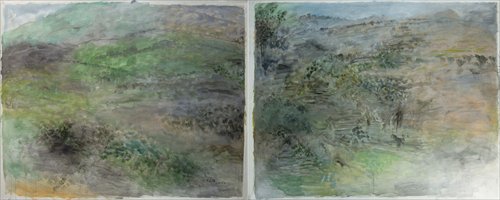

One abstract from Yimeng Mountain series Photo: Courtesy of Yu Youhan

One abstract from Yimeng Mountain series Photo: Courtesy of Yu Youhan

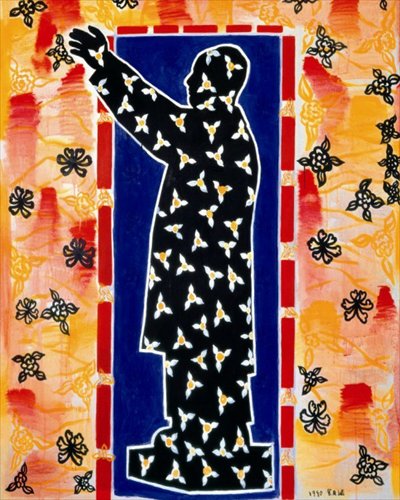

The Waving Mao created in 1995 and auctioned for $709,000 in October 2010 at HK Sotheby's Photo: Courtesy of Yu Youhan

Unlike early generations of modern Chinese artists like Wu Guanzhong and Chen Yifei, or current ones like Wang Guangyi and Ding Yi, all who have rocked the art market with their different styles of work, Yu Youhan has remained more like a hermit and somewhat oblivious to the greater art scene. Nevertheless, he is an artist that has left a heavy imprint on the history of modern Chinese art.

In the words of famous artist Zeng Fanzhi (who ranked No.2 on the 2013 Hurun Art List), Yu is an important link in connecting the artistic styles of early and later generations of Chinese artists of contemporary China.

Despite being widely known for his political pop art as early as the late 1980s, Yu, reaching his 70s this year, just unveiled his first solo exhibition in Beijing, which runs from June 23 to August 17 at the Yuan Space.

Recording the times

Spanning a 40-year-long artistic life, Yu's works are in diverse types ranging from impressionism to abstract paintings. But it's his political pop art that earned him a broad reputation both at home and internationally, especially his serial Mao-themed paintings. And with some new art works emerging as this year marks the 120th anniversary of Mao Zedong's birthday, visitors at the exhibition may be interested in noticing a different Mao in Yu's works.

Though first introduced from its Western origins in the 1980s, pop art in China was naturally integrated into the local political atmosphere under the paintbrush of Chinese artists.

Unleashed from the binding 10-year-long period of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), artists then snatched the opportunity offered by the much freer social environment of the 1980s to record that special period they had just experienced.

Various typical images during the Cultural Revolution like big-character posters, red armbands, as well as political figures (mainly Mao) appeared in those pop art works. The artists took either an ironic or humorous tone to reflect their attitudes toward that period of history. However, different from other leading political pop artists then like Wang Guangyi and Zhang Kexin, Yu's works seemed less political and more ambiguous compared with other straightforward ironic or critical paintings.

"I think my pop art is more like historical paintings, but not that realistic type that plainly displays history," said Yu, "It's impossible to tell the history (of that time) clearly through an artwork." But still, as an artist, Yu tried to paint his memories and attitudes toward that certain period.

In one of his paintings called Talk to Hunan People, Mao sits with several local farmers happily talking to each other. It looks like a joyful and harmonious occasion underscoring Mao's leadership cohesion just the same as is depicted in many mainstream paintings of political figures. But in the background of the painting, Yu used a dazzling red color to fill in the space. In fact, this kind of color was employed in many of Yu's Mao-themed paintings.

"In my painting, Mao is just a person, but not a common person since he is a leader after all, and the contents of the painting illustrate his identity," said Yu. "The vast red background reflects people's overly crazy desire to worship him during that period of history," Yu told the Global Times.

Using a series of popular cultural elements like phoenix or peonies then as a medium, Yu incorporates a faint hint of attitude that can be seen as critical, humorously teasing or affirming his portrayal of Mao. And compared to works of a similar theme during late 1980s and mid 1990s, Yu's political pop works can be regarded as the most visually amiable.

"I'm very opposed to those distorted figures featured in some works. Pop art is also a kind of art, being able to appreciate it aesthetically is necessary," he added.

And with his choice to artistically keep away from those overtly distinctive pop works, Yu was able to accomplish the uniqueness he is now famous for, especially with his Mao series of works, which has now attained an underlined value in the auction market. Most of Yu's works are now in the hands of foreign collectors, and their price tags run into millions of yuan.

Return to the abstract

While Chinese art in the 1980s was still limited to traditional landscape, figure portrayal and still-life paintings, the implanted pop art certainly opened a door for local art to develop more diversely and with more of a popular orientation. But it turned out to be short-lived in the country.

Gradually fading out from creating pop art works in late 1990s, Yu began to pick up the abstract style that he had tried in his early years of painting. The most distinctive elements in those works are dots. Yu explained his use of this symbol in the works by saying, "Dots (or circles) are a spiritual concept, consistent with the philosophy of Lao Zi (founder of Taoism), which emphasizes respect for nature and the natural rules of development."

Maybe entering the age of philosophical living, Yu applied his thoughts in almost every piece of his abstract art works created in recent years. Like the Yimeng Mountain series since 2002, the artist used dots as the main element, combined with other various symbols like lines and strokes, to reflect the beauty of nature and deliver his scorn toward the artificial and repetitive construction found in urban areas.

Reflecting history and social reality seems a persistent theme in Yu' works. Art critic Huang Ziping once commented on Yu's works in the 1980s saying they were a collective expression of China's cultural environment in and since the late 1980s.

And Yu himself also agrees on the importance of connecting social realities in art. "Too many art productions today are purely seeking to gain commercial benefits, even at the price of distorting art to attract the eyes," he said, "and that's why I always told my students never to take art as a living, because it will destroy your art."