Freelancers struggle to get images on sensitive topics shot, published

A priest and his followers mourn a deceased person in Zhouzhi, Shaanxi Province, in 1997. Photo: Courtesy of Yang Yankang

A famous photo in Yang Yankang's Tibetan series showing a person among papers. Photo: Courtesy of Yang Yankang

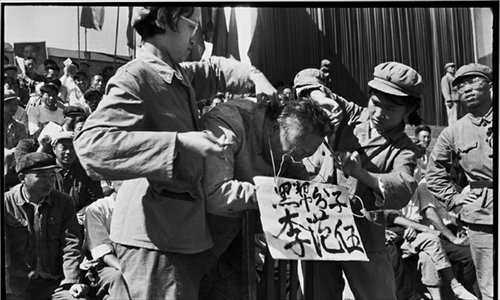

Red Guards stage a public event denouncing then Heilongjiang governor Li Fanwu during the Cultural Revolution. Photo: Courtesy of Li Zhensheng

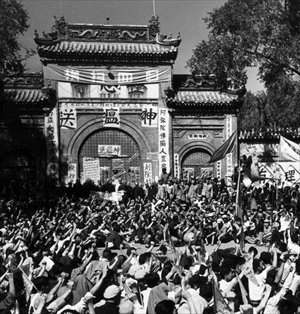

Red Guards gather in front of a temple in Harbin, Heilongjiang Province on August 24, 1966, with banners blasting words like "Send evil gods away." Photo: Courtesy of Li Zhensheng

Photography is often the best medium through which to convey a full picture of history, with its triumphs and setbacks.

But in a country like China, where some visions of the past and the realities of the present are still sensitive and discouraged, photographers try any means to show what they believe to be the hidden reality in this country.

Li Zhensheng, a Chinese photojournalist who captured some of the most telling images of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), told the Global Times that even today, he still has trouble exhibiting all his pictures in China.

After living in the US for 15 years, he was invited to attend the Dali International Photography Festival earlier this month. But his photos had to undergo strict screening to be exhibited.

"The local publicity bureau and I had our differences on which photos should be on display. I always want to choose strong images while they always reject dark or depressing photos. They have their own criteria," said Li, who added that he surrendered the choices of pictures to the publicity bureau.

Years after the Cultural Revolution and although China has faced up to the horrors of that time, graphic representations of it remain difficult.

Shifting attitudes

Independent photographers face a raft of doubts and harassment when they go deep into remote and poor areas of the country. They may be aiming to photograph a wide range of sensitive topics, including the religious life of Tibetans, Catholics in rural areas or poverty-stricken people in western China.

Yang Yankang, a freelance photographer who has spent the past decade taking pictures of various aspects of Tibetan Buddhism, spoke about the difficulties he endured during his arduous adventure in Tibetan areas.

"I am a photographer and I have to live with monks in temples or Tibetan families for weeks on end to observe them closely. But I found it more and more difficult to be accepted by locals in recent years," said Yang.

Due to heightened sensitivity, outsiders who visit these remote locales are asked to register at the management committee in temples or villages since riots in Lhasa in March 2008.

Not being employed by any specific media outlet, Yang found it more difficult to prove his credentials and convince the officials of his motives.

Without official invitations or press cards, the independent photographers may often find their explorations offending local authorities and landing them in hot water.

Some of them have been blacklisted by local public security bureaus, for their frequent "suspicious" contacts with religious groups. Anytime they appear, public security officials may dog them and record their movements.

"I take photos out of my love for the country. I want to show the full picture of Tibetan people's spiritual outlook, so more people will appreciate the importance of such beliefs. However, the local authorities assume my motivations are different," said Yang, who believes he is on the blacklist of the Shaanxi provincial publicity bureau after having been deported from the province twice.

From 1991 to 2001, Yang spent more than eight months a year, living with nuns, monks and other Catholic faithful in rural areas of Shaanxi, Qinghai and Shanxi provinces. From 2003 to 2013, he visited temples in Tibetan areas and knocked on thousands of doors, photographing religious aspects of people's lives.

In 1998, Yang went to a church in a village in Yulin, Shaanxi. As he had visited the church many times, he arrived through the main gate. But this time, plainclothes policemen followed him, took him to the local police station, checked his identity, held him for half a day and escorted him out of the area. From then on, Yang tried to keep a low profile and asked churchgoers he knew to help him access the churches.

"I had to stash my photo gear bags at my friends' home and visit the churches with them without being spotted as an outsider. After all, it is a closed community," said Yang, who has come to believe in certain aspects of Catholicism and Buddhism through his work.

Like other independent photographers, Yang supports himself and maintains an austere life, despite some commercial success. Yang's devotion to the life of religious people has garnered him a measure of fame. A total of 50 of his pieces have been collected by the Guangdong Fine Arts Museum, Xinhua reported.

In 2009, his images of Tibetan Buddhism were awarded the Nannen Prize in Germany, which allowed him to exhibit widely internationally. At the photography festival starting early this month in Dali, Yunnan Province, one of his snapshots of Tibetan Buddhism life was bought for 21,138 yuan ($3,454), the highest sale at the festival.

But he has never forgotten the bonds of kinship that tie him to the areas and the people he shoots. "I still feel grateful when I knocked on the door of Tibetan houses and kind grandmothers always offer me zanba (roasted barley flour) and milk tea. They have taught me the power of religion," Yang said.

However, much like Li Zhensheng, acclaim overseas does not translate to a free rein at home.

"Photos about Tibetans are always sought after on the market. All photography depicting social problems, especially those recording the lives of those on the fringes of society, always win applause," Hong Haibo, a spokesperson for the Dali International Photography Festival, told the Global Times. "But we must remain cautious."

Do the opposite

"As a photographer, you have to always do the exact opposite of what you are told. Be rebellious if you want to show this world in a unique perspective," Li Zhensheng told the Global Times.

While his peers were competing to take positive photos that consisted mostly of high-spirited revolutionaries waving Little Red Books and praising Chairman Mao, Li aimed his camera at the negative side of the campaign.

"Only 'positive' images could be published, so that everyone took photos of the uplifting circumstances. However, our view of history would be incomplete if we lacked images showing the 'negative' side - the most horrifying moments when people were being publicly denounced, tortured or sentenced to death. I had to record the negative side," said Li, now in his 80s.

It took great effort for Li to hold on to these precious images. He hid the photos and negatives underneath the floorboards during this period of revolt against traditional values.

In 1969, when the campaign escalated and implicated Li, he and his wife were sent for reeducation in rural areas, living with farmers and studying the theories of Chairman Mao. Before leaving, he cautiously entrusted one of his acquaintances to keep the photos and negatives for him until they were first revealed publicly in March 1988 in a photography competition held by the Chinese Press Association.

It remains a sore point for Li that his book Red-Color News Soldier, an album of his photos taken during the Cultural Revolution, has not been published in China. "We have to face history squarely and let later generations have complete access to that period," Li told the Global Times.

The situation is slowly evolving. Li has been invited to various photography exhibitions in recent years, including the Dali festival. Li's pictures have become recognizable and it is a distinct possibility that his absence from such a famed festival would provide more cause for discussion than his presence.

But many photographers who do not enjoy Li's limelight fail to get published if they focus overly on sensitive topics.

Huang Xinli, one of the first batch of photographers who looked at Catholics in rural areas, found out that even photographing churches with overt support from religious leaders can be tricky.

Huang was entrusted by the bishop of Shaanxi in 1997 to take photos of over 280 churches in the province. Bringing along a recommendation letter from the bishop, Huang got access to all these churches and took more than 40,000 photos in six months.

Even though Huang pocketed the recommendation letter, he was still interrogated by security officials and policemen.

"Chinese authorities maintain a comparatively conservative attitude toward religion. They don't want too much publicity on the topic," Huang told the Global Times.

Huang's long-time wish of publishing an album of his photos has still not come to pass, as no publishers want to touch this sensitive topic. In this, he is far from alone.

Ongoing troubles

Collections of images regarding sensitive topics can have their publication plans yanked at any time.

Gao Xiaohong, an associate professor of photography from the Shanghai Theatre Academy, recalled that five images taken by a Chinese photographer were withdrawn from the Shanghai International Photography Exhibition in October last year, due to their "political sensitivity."

"Normally, any venue hosting photography festivals and exhibitions remain highly alert. They screen all the images, to make sure each and every photo is 'politically correct," said Fan Xiaoqiang, secretary-general of the China Artistic Photography Society.

"Especially when we receive photos regarding ethnic groups, religion or other sensitive issues reflecting strong social conflicts, we invite experts to help screen the photos and make sure there are no images that have the potential to cause misunderstandings."

But Gao countered that a developing society must offer photographers more opportunities to expose their work.

"Chinese authorities have gradually included religions into the category of culture and have slightly relaxed restrictions concerning publicity of such topics. As long as there is no strong, symbolic content, these photos can be on exhibit publicly," Gao told the Global Times.

But books remain a different proposition, Gao said, adding that screening in book publishing is much stricter.