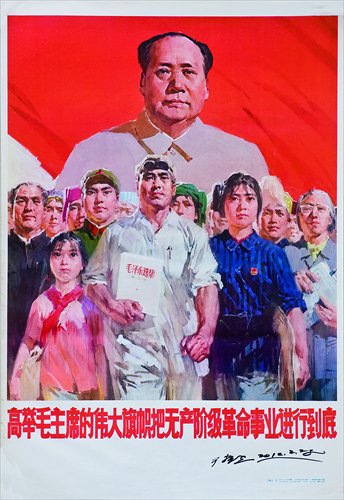

Poster boy

A 1977 poster by Yu

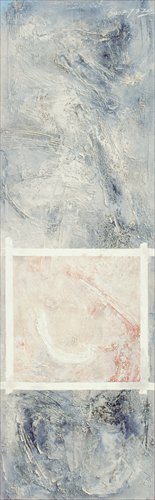

Yu's abstract art

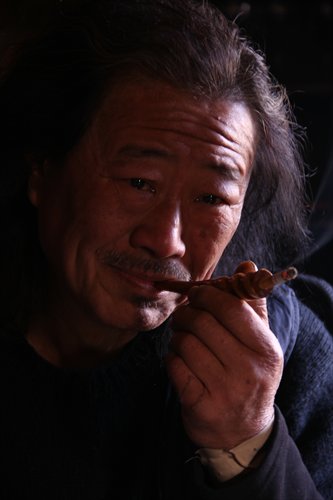

Yu Zhenli Photos: Courtesy of Infinity Culture & Art

Born in 1949, the same year as the foundation of the People's Republic of China, Yu Zhenli's life seemed destined to be connected with China's modern history.

Every political movement after the foundation was in need of massive amounts of political artwork. Posters were one of the most effective ways of communicating ideals. That's how in 1967, 18-year-old Yu received widespread exposure in China and even influenced the style of that period.

Yu's work has become more famous than the artist himself, especially for people who lived in the 1960s to the 1980s.

Yet in the midst of his success, Yu made a staggering choice in 1994 - to leave mainstream society and live in solitude. He moved to a village near Dahei Mountain in Dalian, Liaoning Province, to get away from the fast pace of the city.

The number 18 is special for Yu. He started his career at the age of 18, and then lived as a recluse for 18 years.

During those 18 years of "self-deportation," his creative output entered a whole new level.

His latest exhibition, Self-deportation - Yu Zhenli Solo Exhibition, held from September 24 to October 14 at the Today Art Museum in Beijing, gave a full retrospective of his 40 years in art.

In a dialogue before the opening of the exhibition, Yu, together with curator Li Xianting and art critic Liu Xiaochun, shared with the media thoughts about his career, especially the years he spent living in a village.

200 portraits of Mao

Yu was noticed by officials of the Communist Party in 1967 for his perfect copies of the portrait of Chairman Mao. This laid the foundation for his art career creating political posters from 1967 to 1979.

Sticking to the political requirements for art during that era, his posters are full of the color red and positive images. His passion for creating burned brightly through the images of smiling people, allowing his unique style to shine through the artistic constraints.

During those 12 years, he finished nearly 200 copies of Chairman Mao's portrait as well as more than 80 vibrant political posters. Among them are famous works about the advancement of socialism and the denouncing of the Gang of Four.

In the 1980s, Yu moved past posters and tried expressionism and abstract art.

But the biggest change came when he abandoned his fame to return to nature. This was the choice of an artist who follows his heart to pursue the true meaning of art.

Self-imposed exile

"It's very simple - just to relax," Yu replied whenever asked why he chose to leave city life. The burden of fame caused him to exile himself.

"In the market economy, you have to run all the time. I was really tired of running, so tired that when I lied down, I lied down for 18 years," Yu explained to the media during the dialogue.

Li Xianting, an influential art critic and curator of the exhibition, said that the period when Yu left was the time Chinese art started to receive attention from the West. Artists of that time became stars in the art world. Yu's behavior was a rejection of that vanity.

During his 18 years in the village, Yu never stopped creating. His artwork evolved from 2D to 3D. With rocks from the mountain, waste from urban construction, abandoned tires, glass bottles and TV monitors, he built houses and studios by himself or with the help of a few friends.

The walls were built mainly with waste material and decorated with symbols. The countless bottles and TV screens were particularly conspicuous in his designs.

"They are more like sculpture rather than architecture, because they are too manual, too personal," Li remarked. "These houses carry the personal attitude and feelings of Yu, using the waste of urban and modern life, intentionally or unintentionally, to ridicule crazy urbanization."

Together with those houses, Yu also created many paintings and amassed a large pile of notes. In the notes are his ideas about art or social issues and drafts of paintings, all drawn by hand.

Blurred lines

There are clichés that profess that art is life and everybody is an artist. But it seems few can clearly define the relationship between art and life.

"Life is art, but not everyone's life is art," Li said. "[Yu's] life is the reflection of real life."

According to Li, Yu was affected by Western realism. While influenced from the outside, Yu then used this realism to capture the real China.

Another art critic at the dialogue, Liu Xiaochun, explained this with Yu's artwork. In one of Yu's pieces from 1987, Lao Jiang, his style changes entirely - symbolism replaces realism, gray replaces red - and yet the farmers in the picture still reflect real-life experiences from that time.

"He intentionally blurs the boundary between art and life," Liu said.

The exhibition used a reverse chronology to demonstrate Yu's work through the decades, including notes and video footage. Li said self-seclusion provides an artistic respite for those feeling tired, especially for those who suffer mental fatigue from the hustle and bustle of society and try to find a place of peace and reflection.

"(He) invites audiences to see his real life in Dahei Mountain," Li said.