Following the thread

In a tranquil two-story building shadowed by towering trees, Chen Huaqiong is attentively stitching a small piece of canvas with a landscape scene, by hand alone. Together with another three embroidery artists in the room, the 28-year-old is among the few third-generation (district-level) inheritors of the increasingly rare art form, Gu embroidery.

With a history of more than 400 years, dating back to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), Gu embroidery is known for its superb technique, graceful patterns and the extremely high level of artistry involved. It's also referred to as embroidery painting, given its lifelike interpretation of masterpieces by ancient painters and calligraphers.

The art form was created by the ladies in the family of Gu Mingshi, a jinshi (advanced scholar, a level in the ancient imperial exam system), from Songjiang district. Gu embroidery is also believed to have exerted a substantial influence on other embroidery types such as the Su, Shu and Xiang styles.

Chen Huaqiong, a third-generation inheritor of Gu embroidery, stitches her latest work.

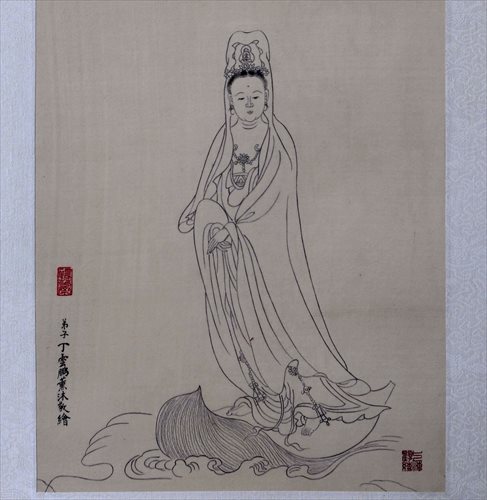

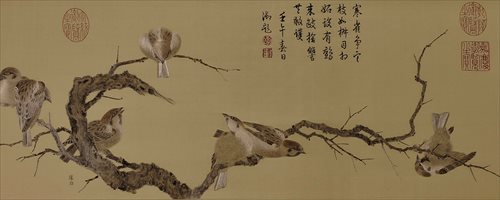

Gu embroidery works

Gu embroidery works Photos: Ni Dandan/GT and courtesy of Fu Yongping

In 2006, Gu embroidery was listed as a State-level intangible cultural heritage. But its inheritance situation didn't improve much thereafter, according to Fu Yongping, a second-generation (city-level) inheritor of the art.

Keeping the flame alive

Now in her 50s, Fu Yongping was first acquainted with Gu embroidery in 1978 when her then employer, Songjiang Art Work Factory, organized a workshop aimed at preserving the local art form, which had very few skilled masters. Fu was one of the 10 to join the workshop, and their teacher was Dai Mingjiao, the first-generation and State-level inheritor of the art who is now in her 90s.

As one of the five second-generation inheritors of Gu embroidery, Fu has witnessed the ups and downs of the art. Although the lack of Gu embroidery masters has always been a problem, Fu said once in the 1980s, Gu embroidery was very popular not just among Songjiang natives but also foreign visitors.

"The then Songjiang county foreign trade and commerce authority arranged for foreign visitors from the US, France, Japan and Southeast Asian countries to visit the factory to view our works. They spoke highly of them and purchased some," Fu told the Global Times.

However, it takes at least three months to complete even the smallest of Gu embroidery works of 24 square centimeters, meaning workers struggled to make ends meet. The factory used profits from other sectors to fund the workshop. Eventually, only five of the students stayed on to become second-generation inheritors.

In the 1990s, with the closure of the factory, the team didn't expand, and they separated to work for different private organizations to promote and pass on the art form in their own ways. Even after the art form was designated an intangible cultural heritage, these most authoritative names in the art were not brought together by any government organization to make a bigger impact in the art's promotion.

"I miss the 1980s when the factory would organize showcases of our works at Shanghai culture and art exhibitions. These days, we don't even know about when such exhibitions will be held and how to apply to take part," Fu sighed. "I'm often envious of Su embroidery artists since the Suzhou government gives them much support." Fu now works for a private organization dedicated to the promotion of Gu embroidery.

Large skill set

According to Fu, Gu embroidery is particularly demanding as a master needs to be skilled in painting, calligraphy and seal script. On an empty canvas, one needs to draw an outline of the work with a writing brush. The selection of threads in all colors tests one's understanding of the original art pieces. "That is why I call Gu embroidery workers artists. They don't simply copy an ancient work. They are recreating the masterpieces in their own ways," Fu said.

Given the tough demands, Fu believes that graduates from art academies would be ideal candidates for this job. But when she sought potential students, things didn't work out as she had expected. "It's a lonely thing to be with the threads and needles all day long. And to be realistic, graduates from art academies can soon find a job that pays decently. But Gu embroidery takes at least five years of training before a practitioner can independently work on a piece. And it's never a lucrative job."

In contrast to what Fu had imagined, her current four students had no foundation in either calligraphy or painting. "Now my standard is that as long as you want to learn the art and can persist in the work, I'll teach you as much as I can. I've been working on Gu embroidery for more than 30 years and I don't want to see the skill die out in my generation."

To her comfort, the four students of hers, all Songjiang natives, have become recognized third-generation inheritors of Gu embroidery. But they had their struggles before eventually settling down as full-time embroidery workers. Some tried other professions, including cashier in a supermarket and worker on a factory production line.

Chen Huaqiong is one of them. Although she picked up the embroidery form the age of 16 when Gu embroidery was promoted in a hobby group in her high school, Chen chose computing as her college major. "I couldn't buckle down to it at the beginning. Repeating the same moves again and again with the threads and needles bored me," she told the Global Times.

Chen said it was only five years ago that she began to comprehensively learn calligraphy and painting, and eventually become able to focus on the art. "Anyway, it's been more than 10 years. It's a pity if I waste all the effort I've put into learning. And honestly, it's not just a job, but also a hobby for me now." Chen revealed that she received an income of around 5,000 yuan ($799) a month, with which she says she feels quite satisfied.

Editor's note

According to UNESCO's definition, an "intangible cultural heritage" includes traditions or living expressions inherited from our ancestors and passed on to our descendants, such as oral traditions, performing arts, social practices, rituals, festive events, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe or the knowledge and skills to produce traditional crafts. It has to be traditional, contemporary and living at the same time, inclusive, representative, and community-based. The safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage is an important factor in maintaining cultural diversity in the face of growing globalization. An understanding of the intangible cultural heritage of different communities helps with intercultural dialogue, and encourages mutual respect for other ways of life.

The Shanghai Municipal Government has designated 157 traditions as Shanghai's intangible cultural heritages.

The Global Times Metro Shanghai culture page will introduce one intangible culture heritage and interview their current inheritors every month.

Newspaper headline: Practitioners battle to keep an ancient art alive