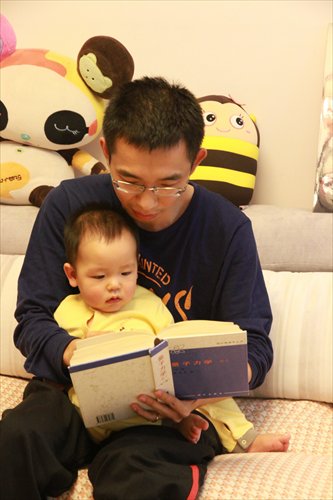

Xing Bing reads Quantum Mechanics to his 11-month-old son. Photo: Courtesy of Xing Bing

After dinner, Xing Bing, 29, an assistant manager at a trust fund company in Beijing, sat down on the sofa. He then picked up Quantum Mechanics (2000), a book he read while doing his doctorate in physics at Peking University, reached for his 11-month-old son, opened the book and started to read aloud.

Xing has been reading to his son from the advanced science book for more than one year since his son was just a fetus.

"Come little pudding (the nickname for his son)," Xing said, drawing the child closer.

"Today we will talk about the different representations of quantum states. Each quantum computing operator is different in different representations. It's the same with you. You are a baby at home, you will be a student in school, and you will be someone's colleague at work."

Seemingly interested in the beginning, little pudding soon crept out of Xing's arms and went crawling and gurgling merrily on the floor, oblivious to his father's words.

"Some of my friends think that I am crazy for reading such an enigmatic science book to an 11-month-old baby because the baby wouldn't understand what I am talking about at all, but I believe it can be of great help to my child's future development. It can help him develop rational and logical thinking," he said.

Xing is not the only father to introduce advanced science topics to his infant. Just a week before, Mark Zuckerberg, the CEO of Facebook, posted a picture on his Facebook page of himself and wife Dr Priscilla Chan reading Quantum Physics for Babies to their daughter Max, who was two weeks old at the time.

Although he explained in the caption that he was kidding about the quantum physics book, Zuckerberg said he is planning to read World Order by Henry Kissinger to Max. He described the book as "about foreign relations and how we can build peaceful relationships throughout the world."

Despite the explanation from Zuckerberg, the post has still been read more than 40 million times within a day after it was posted, with most Net users around the world talking about how their children have lost to Zuckerberg's child from scratch and whether it's useful to start science education from infancy.

Huang He's 5-year-old son conducts a chemistry experiment on his own. Photo: Courtesy of Huang He

Building a logical mind

When Xing reads to little pudding, all he seems to do is crawl on the floor, throw his toys around, and sometimes doze off in his father's arms, but Xing remains adamant that his efforts will reap dividends in the future. He believes that introducing advanced academic content to his child while he is still an infant can exert a subtle influence subconsciously and help develop rigorous and logical thinking.

"Physics is just like Chinese and English; it's a language to describe the world in the way of mathematics. It's a very logical and rational language compared to other languages," Xing said. "By studying physics, people can analyze the causes and predict the consequences of different things more clearly. That way of thinking will be very beneficial in my son's future study no matter what kind of work he will do."

Xing conceded that there will be little evidence of information retention in the early stages or even the first few years of his son's life but said he is more than up to the task.

"We can only let the child get in touch with as many things as possible, every syllable in music, every color and each complicated term in physics. Over time, those fragments of knowledge will penetrate the baby's brain cortex, and form a knowledge system and influence the baby's thinking naturally," Xing said.

"By reading physics to my son every day, I believe he will gradually get used to the language of physics, have a strong sense of causality, and form the habit of thinking and getting to the root of things," he said.

Huang He, 38, a chief technology officer at a Beijing-based IT company, started to teach the sciences, including physics, chemistry, programming and math, to his now 5-year-old son since he was an infant.

Unlike Xing, Huang didn't read highly-advanced scientific books to his son. Instead, he imparted knowledge using everyday scenarios, doing experiments and playing games with him.

For example, when his son was 1-year-old, he took him outside, showed him the sun and explained why people's eyes could see the light - still physics, just a simpler version, one that his son can better understand. For chemistry, he let his son mix baking soda with vinegar, and explained how carbon dioxide is formed. He found innovative ways to introduce math and programming into his child's life as well.

"I think the sciences can help my son have a better understanding of the world. It can help him see the stereo structure behind what seems a flat world, and help him develop a better logic, and stimulate him to be more curious about the world," Huang said.

Huang's method is already paying off. His son once won first prize in a lottery draw organized by his kindergarten using the knowledge of probability by analyzing how many prizes had already been won and deciding which jar he should pick.

"He also shows better manual dexterity than most other children his age. As a 5-year-old, he often plays with his experiment box that has light bulbs and different chemistry ingredients. He really grew into the scientific stuff," Huang said.

Unforeseen effects

Although Huang's child shows better logical thinking and fine motor skills than his peers, Huang is concerned that he is introverted.

"He keeps to himself and doesn't like to play with other children," Huang said. "I think it's because he puts much of his energy into exploring himself and scientific phenomenon. I wish he could be more active and better at socialization."

Chen Zhilin, a child expert based in Chongqing, warned parents that starting scientific education too early, especially by way of cramming (intense study), with no regard to whether the child responds well or not, could cause the child to develop a repressed character.

He said it could also cause children to act out and become more rebellious when they became teenagers.

"Children start to become self-conscious at the age of 3. If they don't like the science education but the parents keep pushing them, they will be more prone to rebellious behavior in the future," Chen said.

On average, Chen receives 300 teenage clients a year who are going through a rebellious phase, exhibit symptoms of study burnout or have a volatile relationship with their parents.

"I believe science education at infancy can be beneficial for children to form logical thinking, but the content should be interesting and in a way children can understand, such as having vivid colors or a game in it, and the children should enjoy it. If not, then it will be no good," Chen said.

Liu Jianfei, 20, a computer science major at Carnegie Mellon University, said that his parents started teaching him science at infancy, but they kept the time [length of study] and intensity moderate. He attributes his pursuit of the sciences today to the programming his father taught him at three.

"It made me more interested in the sciences and able to make more progress than most other students," Liu said.

Creative ways to teach science

Zhao Haoxiang, 35, a tech manager at a telecom company in Silicon Valley, has also been teaching his 7-year-old son science from infancy and suggests that parents use games and experiments to teach science.

He recommends apps and games such as Box Island: One Hour Coding and The Foos Coding in Apple's app store for parents who want a fun and interactive way to get their child to learn programming.

"Lego Mindstorms is also a good toy to learn programming. Children learn to build a robot with the Lego bricks and how to program the robot as well," he said. "Parents can also buy some educational toys that teach children physics and chemistry by telling them how to make water or a volcano with various ingredients."

Zhao said that based on his observations, the US has more interesting and creative ways to teach science than China.

"They advocate comprehensive science education, STEM (Science, Technology, Engineer, and Math), and they have more children-suited books and toys for it, so their children's thinking are usually more creative," Zhao said.

"Starting your child's science education at infancy is good, especially in the era of technology, but we need more creative and interesting ways to conduct comprehensive education," Chen said.