Illustration: Lu Ting/GT

My teenage daughter recently finished a 12-day "concentration camp" TOEFL training. She chose this Test of English as a Foreign Language course, which cost me 23,000 yuan ($3,343), after a month of searching. When we first started looking for a short-term winter holiday language course for her, I anticipated that at most it would cost just several thousand yuan. But I quickly realized that my knowledge of China's ESL market is still stuck in 2004.

Pretty much every education company I contacted quoted between 10,000 and 30,000 yuan for only 12 days of classes. Put off by these outrageous prices, I initially suggested to my daughter that she study TOEFL on her own using resources and materials that are available for free online. But she screamed at me that all of her peers were taking actual TOEFL classes, so she should be able to too.

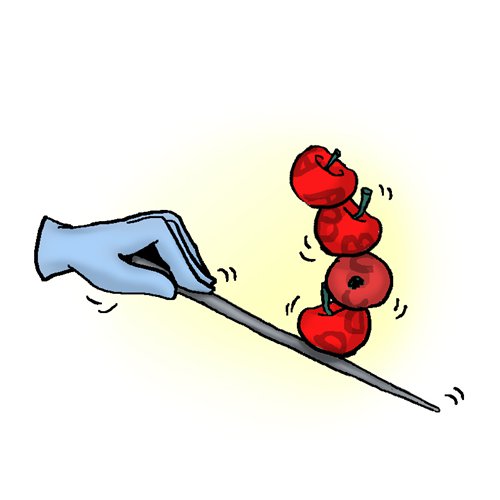

Although it's impossible to reason with a teenager, I explained the old tried and true adage "practice makes perfect." So long as she put her mind to it and spent time reading the material, she could achieve a good TOEFL test score and get accepted into a foreign university.

After quarreling, however, I finally relented and agreed to help find her a training center. I asked friends on my WeChat parenting groups about their experiences and recommendations while simultaneously cold-calling language centers that I always see advertised.

They each claimed that they were "unique" in the language market, with "famous" teachers and "outstanding" students who achieved high scores in international exams. All of the sales people, in their canned pitches, urged me to choose a one-on-one class for my daughter, because the VIP classes "yield better results" than large group classes.

Naturally they would say this, as private classes are far more expensive than group classes - about 1,000 yuan per hour! Even if I were able to afford this elite level of training, the sales people disclaimed that ultimately they "are not responsible" for exam performance, as "every student is different."

It's important to note that the centers I contacted are all licensed and certified with the local business bureaus. They are legal entities and not up to anything dishonest (if they were crooked, they probably would have guaranteed me great results). Their exorbitant fees are justified due to the most basic economic principle: supply and demand. They can get away with charging so much because local parents are willing to pay it. Language schools might fall under the auspices of the education industry, but really this is capitalism in its purest form.

China's private education market has matured after two decades of trial-and-error experimentation. And while many such businesses come and go (sometimes leaving teachers unpaid and parents unrefunded), there is an equal number of established, reputable companies to choose from. It just depends on how much a parent is willing to pay.

Nonetheless, as someone who once operated my own private language center back in the day, I remain slightly dubious of these "new-school" centers that are known for teaching shortcuts and tricks to memorizing materials that help get students high scores on tests. This method seems to defeat the whole purpose of learning and takes all the fun out of acquiring knowledge.

Westerners often accuse today's Chinese students of lacking creativity and innovation, and modern language centers that focus strictly on rote memorization reinforce that negative impression. But having previously participated in a military-style camp that she did well in (see my TwoCents "Military training can cure China's spoiled-child illness" 2016/9/7) my daughter finally chose for herself a high-pressure TOEFL "concentration camp" that would trigger her competitiveness. She urged me to secure a slot.

For millennia, Chinese students have gone to school to learn. Only in recent decades have they gone to school to be "trained." There is a huge difference in these concepts. Knowledge has become obsolete in this new era of education; only answers matter anymore. Thus, the question students should be forced to answer when applying to universities is not what they know but if they learned it themselves or by being trained.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Global Times.