METRO SHANGHAI / CITY PANORAMA

Ancient Chinese embroidery makes modernized comeback

Needlework nation

Embroidery and needlework used to be a required skill for every Chinese woman living in olden times. A newly married bride was usually judged by her in-laws according to the handicrafts she made and brought to her new home as a dowry. Women in different regions of China developed their own genres of embroidery, and some embroidered handicrafts were considered works of art rather than simple daily necessities. Centuries later, however, needlework skills are no longer required of the average Chinese woman.

In Shanghai, the two most famous embroidery crafts - woolen needlepoint tapestry and Gu embroidery - are listed as Chinese intangible cultural heritage items but face a drastic shortage of practitioners and inheritors.

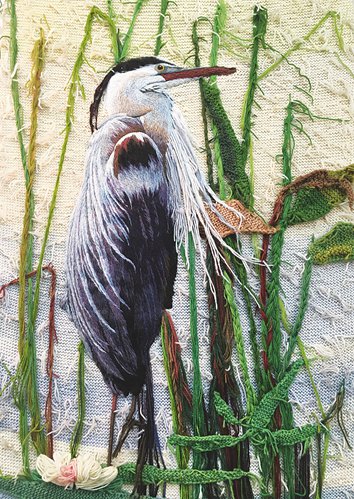

Shanghai's woolen needlepoint tapestry is a kind of skilled embroidery using colored wool yarn to create vivid patterns and designs with a distinct gradation style on a fine mesh canvas. It is called "eastern canvas" because it appears as realistic as oil paintings depicting human figures, birds and flowers, animals and landscapes.

This needlecraft was listed on the national intangible cultural heritage list in 2011. However, as most craftsman masters are in their senior years and young practitioners are unwilling to pursue this industry because it is time-consuming and low-rewarding, woolen needlepoint tapestry is facing a drastic shortage of practitioners and inheritors.

Different from other traditional Chinese embroidery, the origins of the woolen tapestry can be traced back to 14th-century Germany, where geometric woven patterns were featured on peasants' clothes and wall carpets. It came into prosperity in England between the 17th and 19th centuries. It was first introduced into Shanghai by foreign missionaries and merchants at the beginning of 20th century as decorative fabrics for slippers and handbags.

Local artisans in Shanghai integrated traditional Chinese silk embroidery techniques into the Western woolen needlepoint tapestry and created their own style, which later became known as the "Shanghai-style" of woolen needlepoint tapestry.

The manufacturing procedure for woolen needlepoint tapestry is fastidiously divided into three major steps. Artisans first scale up or down the original image or painting onto the fine mesh canvas. Then they dye the yarn into different colors according to the original image. Last, they knit the contours, the dark-colored areas and the small details.

Upgrading an ancient art

Usually, 500 grams of wool yarn contain 976 threads, with each extending only 1.4 meters. Artisans have to constantly thread their needle when one thread is used up or when they need to switch colors. In order to make the artwork more colorful and vivid, each yarn is further divided into four threads.

Mixing four threads of different colors makes the color of the embroidery softer, richer and more gradual. With such skills, the artwork of woolen needlepoint tapestry looks three-dimensional and very much like that of an oil painting.

Large-scale woolen needlepoint tapestries spreading dozens of square meters are magnificent. In the rooms of the Great Hall of the People in Beijing hang several large-scale woolen needlepoint tapestries made by Shanghai woolen needlepoint tapestry artisans.

These artisans were led by needlework master Tang Mingmin at the Yangjing woolen needlepoint tapestry protection and heritage base in Pudong New Area. Excellent woolen needlepoint tapestries are given to important foreign officials and institutions as State presents.

However, according to 71-year-old Bao Yanhui, an inheritor of the Shanghai woolen needlepoint tapestry, it is harder to make such large-scale woolen needlepoint tapestries now.

"Woolen needlepoint tapestries are totally handmade and completed using more than 10 different procedures. Artworks made by different artisans differ; every piece is different from the other," Bao told the Global Times. "But there remain only a small number of artisans who can master these skills. At present, there are only seven city - and national - level inheritors of Shanghai woolen needlepoint tapestry in the city."

A top woolen needlepoint tapestry usually takes six to 12 months to finish. Because of its long production cycle and low rewards, many young people show no interest in learning this craft. At the Yangjing woolen needlepoint tapestry protection and heritage base, there are only five experienced artisans; the youngest is 60 and the oldest 77.

Over the past 40 years, the woolen needlepoint tapestry industry has been suffering from talent drain. Meanwhile, the long working hours and slow methods of the craft fail to attract impatient youngsters used to fast-paced lifestyles. According to Bao, they once recruited five graduates, including four college graduates and one who graduated from a secondary school. However, they all quit within just two years.

Bao believes the century-old art requires upgraded, innovative designs to make it survive. Bao's son, Bao Li, a graphic designer, infuses fashion into his traditional Chinese embroidery and applies the Shanghai woolen needlepoint tapestry craft for modern daily accessories such as fashionable handbags and three-dimensional art installations, hoping his cross-over creations can inject new vitality into this ancient craft.

The art of Gu

As Shanghai's other national intangible cultural heritage, Gu embroidery - which originated as early as the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) - is one of the most remarkable styles of Chinese embroidery.

It is considered a "family style" rather than a local style, originating from Gu Mingshi's family in Songjiang district, who became a highly celebrated scholar and artist of his day. Gu embroidery is also called Lu Xiang Yuan embroidery, after the place where the Gu family lived.

Listed in the first batch of national intangible cultural heritages in 2006, Gu embroidery has a "ladylike temperament," elegant and restrained. The silk embroidery uses ultra-fine threads to create highly detailed patterns resembling a traditional Chinese painting.

The needles and threads used in Gu embroidery are very thin. Although the stitches in a Gu embroidery appear to be layered, it feels as smooth as paper.

According to Qian Yuefang, an inheritor of Gu embroidery, the secret to this feature is to divide the thread into eight - or even 256 - threads, to display gradation and harmonize its colors.

To be a successful Gu embroiderer, the artisan must also be an accomplished painter and calligrapher. She is involved with every facet of her work, from selecting materials, drawing outlines and choosing threads from nearly 1,000 colors, to sewing and then fitting the work inside a frame. It can take years to complete just one of these exquisite works of art.

It takes at least three years for an apprentice to master the basic skills of Gu, but it requires over a decade to become a true Gu master. According to Qian, there are fewer than 10 skilled Gu embroidery artisans in Shanghai at present. Although Qian, 63, and her peers have cultivated some young inheritors born in the 1970s and 1980s, it is difficult to pass on this craft to younger, post-1990s generations.

Some young women have expressed their desire to learn from Qian, but most eventually either gave up or took it just as a temporary hobby rather than a lifetime career. Qian suggested that vocational schools and colleges in Shanghai establish Gu embroidery majors to cultivate more practitioners and inheritors.

In Shanghai, the two most famous embroidery crafts - woolen needlepoint tapestry and Gu embroidery - are listed as Chinese intangible cultural heritage items but face a drastic shortage of practitioners and inheritors.

Shanghai's woolen needlepoint tapestry is a kind of skilled embroidery using colored wool yarn to create vivid patterns and designs with a distinct gradation style on a fine mesh canvas. It is called "eastern canvas" because it appears as realistic as oil paintings depicting human figures, birds and flowers, animals and landscapes.

This needlecraft was listed on the national intangible cultural heritage list in 2011. However, as most craftsman masters are in their senior years and young practitioners are unwilling to pursue this industry because it is time-consuming and low-rewarding, woolen needlepoint tapestry is facing a drastic shortage of practitioners and inheritors.

Different from other traditional Chinese embroidery, the origins of the woolen tapestry can be traced back to 14th-century Germany, where geometric woven patterns were featured on peasants' clothes and wall carpets. It came into prosperity in England between the 17th and 19th centuries. It was first introduced into Shanghai by foreign missionaries and merchants at the beginning of 20th century as decorative fabrics for slippers and handbags.

Local artisans in Shanghai integrated traditional Chinese silk embroidery techniques into the Western woolen needlepoint tapestry and created their own style, which later became known as the "Shanghai-style" of woolen needlepoint tapestry.

The manufacturing procedure for woolen needlepoint tapestry is fastidiously divided into three major steps. Artisans first scale up or down the original image or painting onto the fine mesh canvas. Then they dye the yarn into different colors according to the original image. Last, they knit the contours, the dark-colored areas and the small details.

Upgrading an ancient art

Usually, 500 grams of wool yarn contain 976 threads, with each extending only 1.4 meters. Artisans have to constantly thread their needle when one thread is used up or when they need to switch colors. In order to make the artwork more colorful and vivid, each yarn is further divided into four threads.

Mixing four threads of different colors makes the color of the embroidery softer, richer and more gradual. With such skills, the artwork of woolen needlepoint tapestry looks three-dimensional and very much like that of an oil painting.

Large-scale woolen needlepoint tapestries spreading dozens of square meters are magnificent. In the rooms of the Great Hall of the People in Beijing hang several large-scale woolen needlepoint tapestries made by Shanghai woolen needlepoint tapestry artisans.

These artisans were led by needlework master Tang Mingmin at the Yangjing woolen needlepoint tapestry protection and heritage base in Pudong New Area. Excellent woolen needlepoint tapestries are given to important foreign officials and institutions as State presents.

However, according to 71-year-old Bao Yanhui, an inheritor of the Shanghai woolen needlepoint tapestry, it is harder to make such large-scale woolen needlepoint tapestries now.

"Woolen needlepoint tapestries are totally handmade and completed using more than 10 different procedures. Artworks made by different artisans differ; every piece is different from the other," Bao told the Global Times. "But there remain only a small number of artisans who can master these skills. At present, there are only seven city - and national - level inheritors of Shanghai woolen needlepoint tapestry in the city."

A top woolen needlepoint tapestry usually takes six to 12 months to finish. Because of its long production cycle and low rewards, many young people show no interest in learning this craft. At the Yangjing woolen needlepoint tapestry protection and heritage base, there are only five experienced artisans; the youngest is 60 and the oldest 77.

Over the past 40 years, the woolen needlepoint tapestry industry has been suffering from talent drain. Meanwhile, the long working hours and slow methods of the craft fail to attract impatient youngsters used to fast-paced lifestyles. According to Bao, they once recruited five graduates, including four college graduates and one who graduated from a secondary school. However, they all quit within just two years.

Bao believes the century-old art requires upgraded, innovative designs to make it survive. Bao's son, Bao Li, a graphic designer, infuses fashion into his traditional Chinese embroidery and applies the Shanghai woolen needlepoint tapestry craft for modern daily accessories such as fashionable handbags and three-dimensional art installations, hoping his cross-over creations can inject new vitality into this ancient craft.

The art of Gu

As Shanghai's other national intangible cultural heritage, Gu embroidery - which originated as early as the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) - is one of the most remarkable styles of Chinese embroidery.

It is considered a "family style" rather than a local style, originating from Gu Mingshi's family in Songjiang district, who became a highly celebrated scholar and artist of his day. Gu embroidery is also called Lu Xiang Yuan embroidery, after the place where the Gu family lived.

Listed in the first batch of national intangible cultural heritages in 2006, Gu embroidery has a "ladylike temperament," elegant and restrained. The silk embroidery uses ultra-fine threads to create highly detailed patterns resembling a traditional Chinese painting.

The needles and threads used in Gu embroidery are very thin. Although the stitches in a Gu embroidery appear to be layered, it feels as smooth as paper.

According to Qian Yuefang, an inheritor of Gu embroidery, the secret to this feature is to divide the thread into eight - or even 256 - threads, to display gradation and harmonize its colors.

To be a successful Gu embroiderer, the artisan must also be an accomplished painter and calligrapher. She is involved with every facet of her work, from selecting materials, drawing outlines and choosing threads from nearly 1,000 colors, to sewing and then fitting the work inside a frame. It can take years to complete just one of these exquisite works of art.

It takes at least three years for an apprentice to master the basic skills of Gu, but it requires over a decade to become a true Gu master. According to Qian, there are fewer than 10 skilled Gu embroidery artisans in Shanghai at present. Although Qian, 63, and her peers have cultivated some young inheritors born in the 1970s and 1980s, it is difficult to pass on this craft to younger, post-1990s generations.

Some young women have expressed their desire to learn from Qian, but most eventually either gave up or took it just as a temporary hobby rather than a lifetime career. Qian suggested that vocational schools and colleges in Shanghai establish Gu embroidery majors to cultivate more practitioners and inheritors.

An artisan observes an image while creating a woolen needlepoint tapestry. Photos:Du Qiongfang/GT

An artisan is working on a woolen needlepoint tapestry. Photos:Du Qiongfang/GT

Photos:Du Qiongfang/GT

Photos:Du Qiongfang/GT

Photos:Du Qiongfang/GT

Photos:Du Qiongfang/GT