ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

Study uncovers rice’s 100,000 years of evolutionary history

New findings pinpoint China as birthplace

A farmer conducts desilting at a water channel in a rice field in Daleng Town of Zhangwu County, Fuxin City, northeast China's Liaoning Province, June 14, 2023. In 2021, local authorities has promoted the transformation of sandy land along the Liuhe River in Zhangwu into cultivable rice fields, achieving ecological and economic benefit. (Xinhua/Pan Yulong)

Through the scholarly efforts of 13 Chinese research institutions such as the Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Relics and Archaeology, a recently published study has uncovered the 100,000 years of evolutionary history of rice.According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, over 50 percent of the world's population relies on rice in their daily diet.

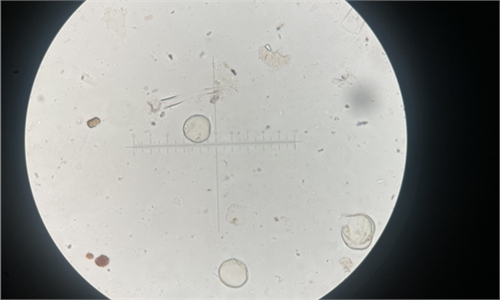

For the study, researchers analyzed phytolith microfossils of rice remains discovered at the Shangshan archaeological site in East China's Zhejiang Province.

The ruins date back to the "early Neolithic Age," archaeologist Yu Pei'er told the Global Times, adding that the site has long been identified as "an ancient field for agricultural activities."

"Over the past decade of excavation, a prolific number of stone wares and charred rice husks have been discovered. Stone items, such as an ancient millstone, were later found, showing that planting and food processing activities occurred there," said Yu.

"Phytolith analysis" retrieves particles of amorphous silicon dioxide that formed between and within the cells of a plant's roots, leaves and fruit.

By combining this approach with other archaeological studies, experts were able to establish chronological layers of earth leading to the discovery of wild rice plants that were distributed in the area around 100,000 years ago.

The discovery has significantly extended the rice's history in China. In 2017, the current project leader Lü Houyuan and his team discovered that rice was first domesticated in China around 10,000 years ago. The result was published in the US journal of the National Academy of Sciences.

The expert, who is also a professor at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, said that the new 100,000 year old evidence sheds light on the "continuous growth trajectory" of wild rice being domesticated by human beings.

"Such an age for the beginnings of rice cultivation and domestication would match with the parallel beginnings of agriculture in other regions of the world during a period of profound environmental change, when the Pleistocene was transitioning into the Holocene," Lü emphasized.

During the past few decades, the topic of rice's origin and domestication had constantly captured global academia's interest.

It was once wildly believed to have originated in Southeast Asia, but since the 1970s, an increasing number of scholars started to be convinced that the rice's birthplace was China.

"To be more specific, the middle and lower reaches of China's Yangtze River is now commonly believed to be one of the earliest birthplaces of rice in the world due to major remains discovered in sites not only like the Shangshan ruins, but also the Hemudu ruins in Ningbo, Zhejiang Province," archaeologist Lu Zhaojun, told the Global Times.

Lü also said that as rice is a globally shared staple food, searching for its origins is as significant as its cultivation by human beings.

"We need to further look into the domestication of the species as well as how it impacted the environmental and climate changes in ancient times," Lü emphasized.

The new research was published in the journal Science in May. Lü revealed that his team's next move is to carry out new DNA analysis to study the genetic changes in rice, and investigate the Shangshan ruins to figure out how rice was domesticated by human beings.

He noted that the rice study is an interdisciplinary research project that also needs the support of other fields such as geology and sedimentology.