ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

Shared exploration

With trowel and camera, Chinese archaeologist makes discoveries about human origins

Archaeologist Li Zhanyang Photo: Courtesy of Li Zhanyang

More than 40 years of scholarly life have accustomed 64-year-old Chinese archaeologist Li Zhanyang to documenting his career through writing, often under the dim light of a lamp.

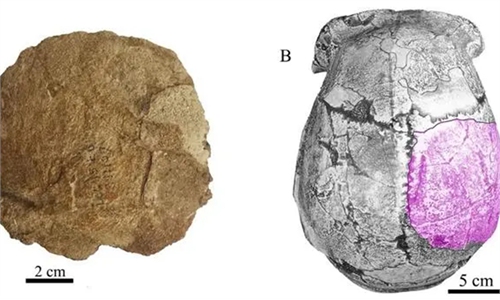

In his recently published book Archaeology of Paleolithic Age, Li wrote about his finds such as ancient human skull fossils. His blocks of text, however, have been interspersed with small photos. While seemingly ordinary, the photos reveal the archaeologist's alternate persona - a photographer - that has also aided in his remarkable archeological journey.

On the cover of Li's new book co-authored by Wang Wei are two ancient axe fossils. Such fossils' pitted surfaces give them a random rock-like appearance akin to rocks one might find in a park. Yet it is exactly these "random rocks" that bear witness to Paleolithic humans' agricultural activities dating back 80,000 to 100,000 years.

'Painstaking work'

Including the two axes, many photos in Li's book were inspired by relics he unearthed from the Lingjing Xuchang Man Site in Central China's Henan Province. Led by Li, the site's archaeological excavation commenced in 2007. Two stellar 100,000-year-old ancient human skull fossils were unearthed, which are named "Xuchang Man." The discovery was sensational, as the fossils held the key to the study of the origins of modern humans in China.

"By researching the 'Xuchang Man' ancient human skull fossil we came to a conclusion: The direct ancestor of modern man in northern China may have been 'Xuchang Man' instead of one from Africa," Li told the Global Times.

Discovering these fossils simultaneously filled him with joy and plunged the archaeologist into deep thought. How could he share these historical discoveries with more people? Putting them in mere textbooks would reach too limited an audience, while photographs would offer a far more immediate impact. Li then embarked on his photographic journey.

Photographing fossils is no easy task. It demands precision and clarity to capture an item's every detail. One of Li's most challenging shoots involved a Paleolithic bird-shaped sculpture of only 19.2 millimeters in length. Aiming to reveal the miniature artwork's features, Li and his students experimented with over 20 types of lighting in the darkroom, adjusting angles and distance, finally allowing for the bird's round beak and long tail to be captured.

"We found that a student's desk lamp worked best," the expert noted, adding that "archaeology is painstaking work that requires patience and persistence."

Li recalls many such grueling tasks. Be it racing against time to capture an ostrich egg fossil within 10 minutes of its excavation, or painstakingly assembling 176 image layers into a single fossil image frame by frame. These experiences have only made him develop an even greater belief in photography's importance to archaeology. He told the Global Times that for archaeologists, a reference image's distorted color or blurred details can affect research accuracy and academic publication quality.

"I want them to see the true archaeological history and feel what I felt when on the site of an excavation," said Li. Named Archaeological Photography and Research Illustration, Li's electives have become one of the most popular courses at Shandong University, engaging not only archaeological students, but also students of history, cultural studies, and other art fields.

'Collective legacy'

Li has not only offered the "true" archaeological history, but also a comprehensive one since, over the past, he has initiated several cross-cultural archaeological collaborations, connecting young Chinese archaeologists with their international fellows.

In 2017, Li and his team headed to Kenya, to excavate around the Kimengich Ruins located deep in the heart of the Rift Valley. Collaborating with Kenyan experts, Li's team discovered two distinct types of axes, one being a larger-sized Acheulean axe, and the other being smaller, showing the characteristics of Neanderthals' Mousterian culture that originated in Europe. The findings show the exchange between ancient civilizations in Africa and Europe.

Following this discovery, the China-Kenya team went on to discover a Paleolithic site in Kenya's Nakuru County. With more than 11 pieces of obsidians and flints discovered, the site was found to have been used by early humans as a stone production site. Li told the Global Times that such finds are not just relating to the ancient African civilization, but also "a quest tied to humanity's collective legacy of human evolution."

Having seen the fruits of the 2017 China-Kenya archaeological project, Li redoubled his efforts to promote international collaboration in Chinese archaeology. In 2018, he spearheaded the "Human Evolution Research" lab at Shandong University. It employs the worldwide study of human origins as a fulcrum, and has collaborated with universities in France, the US, and Sweden.

In 2023, Li's team worked with the University of Bordeaux to discover a 2-centimeter human distal phalanx fossil and a 27,000-year-old "necklace" made of pierced fox canine tooth in Dordogne Province, France.

While recounting how exciting these finds were, Luc Doyon, the project's lead researcher who was formally mentored by Li, told the Global Times that working with the Chinese team allowed him to learn "China's unique archaeological tradition and research methods."

Although not taken by Li, among the photos Li preserved, there happened to be one of him taken by someone else. In the photo, he is half-kneeling on the ground and using a trowel to sift through the soil. He said, "this is the reality of our work; we are just guests to the conversation with the past."

The Lingjing Xuchang Man Site, in Central China's Henan Province Photo: VCG