ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

‘Black Myth’ art show turns legend into trend

Illustration: Liu Xiangya/GT

The ongoing Black Myth: Wukong Art Exhibition at the Art Museum of China Academy of Art in East China's Zhejiang Province stands as an exploration of how to fuse games and artistic expression. As a scholar specializing in game design and art, I have always been engaged in this intersection, and this exhibition offers a compelling case of how deeply games can participate in the language of art.

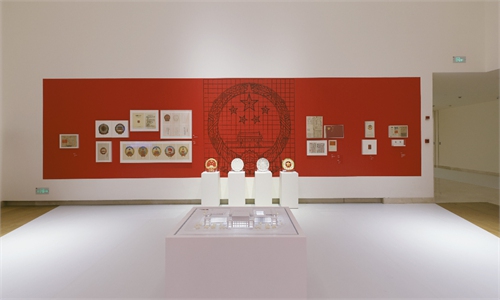

The exhibition features life-sized recreations of core in-game elements, including the statue of the Great Sage, the Ruyi Jingu Bang (Golden-banded Staff), and the head of the Bodhisattva Lingji. It also showcases a rich collection of concept art and design sketches - offering viewers a full glimpse into the creative process from rough drafts to finalized works.

Unlike conventional art exhibitions that focus on concept art and sketches, this one has created a walk-in narrative space. Such three-dimensional storytelling reminds me that the power of culture lies not only in visual precision, but also in the immersive atmosphere it creates.

What struck me most was the large-scale sculpture installation. Opposite the monk of Huangfeng Ridge stands the solemn Buddha head of the Bodhisattva Lingji - two figures locked in silent confrontation, generating powerful visual and emotional tension. Despite the fact that these are the only two sculptures at the exhibition, they freeze the entire space in a single narrative moment, radiating a quiet energy.

Tucked into one corner of the exhibition is a "meditation point" - a direct recreation of the in-game save system. I saw some visitors taking selfies, while a few listened intently to the ambient wind sounds within the hall.

This small design choice disrupted the typical "see and move on" rhythm of art exhibitions, encouraging people to pause - to catch their breath, just as one might in the game.

Notes scribbled on some of the design drafts - such as "inspired by Dunhuang Feitian scepters" or "reference: Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio" - sparked a wave of curiosity and discussion among culturally engaged visitors like myself.

These details invited us not only to look, but to dig deeper into the roots of Chinese tradition.

In my experience, cultural exhibitions often wrestle with a dilemma: They want to evoke emotion and convey ideas, yet fear being misunderstood. However, this exhibition doesn't compromise itself for the sake of accessibility. It doesn't try to guide you with in-game dialogue or plot summaries. Instead, it trusts visitors to feel their own way into this world.

The texture of the sculptures, the handling of sound, the direction of light - all of it serves as subtle cues, leaving vast spaces for visitors to fill with their own interpretations.

This made me reflect on my own design practice. I often find myself debating: "Should I explain why I made this choice? Should I offer a clear historical or conceptual background?"

The exhibition offers a different answer. Cultural expression doesn't have to be a textbook-style retelling - it can be an ongoing invitation to the senses and emotions. The exhibition ignites collective memories of Journey to the West through the language of games, while reimagining those memories through visual design and spatial storytelling.

You can "tell a story," or you can "build an emotion" - but the most important thing is not to rush into explaining who you are. Instead, give your audience a space to feel the world you're trying to create. Let them discover it, one breath, one shadow, one silence at a time.

Looking back at Black Myth: Wukong through the lens of this art exhibition, I realize its true brilliance lies in how it communicates profound cultural heritage through the most approachable means. It doesn't shy away from symbols that Chinese visitors already know. Nor does it get lost in abstract, avant-garde experimentation.

Instead, behind the thrilling battles of demons and deities, it calls us back to the original story of Journey to the West - to reconsider the legacy's deeper themes of heroism, faith, and humanity.

What a game brings is more than just an IP or a new mode of interaction - it represents one of the most integrative forms of storytelling in our time. It can carry tradition, but it can also reconstruct it.

The true significance of this exhibition for me lies in the cultural confidence it conveys.

It does not seek to translate itself through a Western lens, nor does it rush to prove the value of Chinese culture. Instead, it naturally and authentically integrates tradition with contemporary expression.

As Black Myth: Wukong demonstrates, when we possess both the ability to tell our own stories and the means to evoke emotional resonance, culture is no longer a static heritage - it becomes a living, evolving force.

This calm and resolute form of expression is the truest reflection of cultural confidence in our time. It is neither condescending nor overly accommodating, but opens a window through which the world may come to understand China - and the East - through acts of creation.

The article was compiled by Global Times reporter Jiang Li based on an interview with Zhong Yi from the China Academy of Art. life@globaltimes.com.cn