ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

High-tech helps recover ancient Chinese fashion in Mawangdui tomb

Tech enriches history

Mawangdui, an ancient Chinese tomb complex from the Western Han Dynasty (206BC-AD25), in Changsha, Central China's Hunan Province Photo: VCG

When Chinese archaeologists first unearthed a delicate silk textile adorned with swirling "Cheng Yun Xiu" (cloud-riding) embroidery from Mawangdui, an ancient Chinese tomb complex from the Western Han Dynasty (206BC-AD25) in the 1970s, they called it a "pillow cover."

For decades later, this artifact - measuring 100 centimeters in length and 74 centimeters in width - lay quietly in Hunan Museum's collection, its true purpose obscured by a historical mix-up.

Now, new research has flipped the script: It was China's oldest known silk seat cushion.

The breakthrough came from Yu Yanjiao, director of the research center of Mawangdui, who had reexamined burial inventories, excavation photos and the artifact's placement.

Originally, the silk piece was found crushed beneath a robe in the northern chamber of Mawangdui, the burial place of Lady Xin Zhui, wife of the chancellor of the Changsha Kingdom during the Western Han Dynasty.

Nearby, researchers had discovered lacquerware and pottery figurines of musicians and dancers. Most intriguingly, faint imprints of shoes were found near the site - clues that hinted at a banquet scene.

"According to the banquet setting as well as the historical setting, this was a luxurious seat for the tomb's owner, Lady Xin Zhui, to dine on the ground," Yu told the Global Times.

She explained that the cushion, made from a rare warp-faced textile and embroidered with stylized phoenixes and cloud patterns, reflects the extravagant lifestyle of the Western Han elite. But why the misidentification?

A nearly identical "cloud-riding" pillow cover, found draped over a medicinal pillow in the same tomb, had been cataloged correctly.

Both shared similar motifs, but differences in material and craftsmanship - the seat cushions embroidery was notably rougher - went overlooked for years.

"This discovery further refined the excavation report," Yu said.

Printed and colored gauze silk cotton robe Photo: Courtesy of Yu Yanjiao

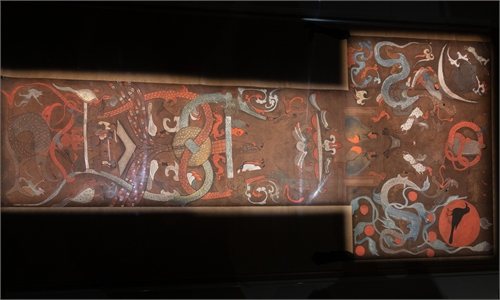

Ancient 'photoshop'Another fascinating revelation comes from the study of the T-shaped silk painting, a 2,000-year-old masterpiece, which has long been a crown jewel of Hunan Museum in Changsha, capital city of Central China's Hunan Province.

The painting was created using a brush and richly colored pigments, and is divided from top to bottom into three sections, namely the heaven, the human world, and the underworld.

The top section - the broadest part of the "T" shape - depicts heaven, with Zhulong, a human-bodied, snake-tailed figure, at its center. To his left hangs a crescent moon, accompanied by a toad and Yutu (Jade Rabbit), while beneath the moon stands a goddess holding it aloft.

However, recent high-tech scans have exposed something startling: The artwork was edited - possibly to keep up with changing fashions.

Using multispectral imaging and X-ray fluorescence, researchers detected multiple revisions.

The newly discovered traces of overpainting include a jade Gui-tablet, originally held by the celestial gatekeeper in the heavenly section, of which only the underdrawing now remains.

In addition, signs of the leopard beside the gate official had been repositioned.

In the human world section, a greater number of figures are shown performing rituals beneath the jade disc, according to Yu. "These weren't mistakes. The edits likely reflect evolving funeral rites."

Yu further said the T-shaped silk painting was created using a brush, with outlines drawn first before coloring and other detailing. The overpainting may have been part of the artist's routine adjustments during the creative process.

However, despite its underdrawing, the unused jade tablet suggests another possibility that the painting might have been prepared well before Lady Xin Zhui's death.

During this time, changed ceremonial practices may have affected the painting.

Holding a jade tablet was once a highly formal ritual gesture, commonly seen during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods (770BC-221 BC).

However, this ritual may have evolved by the Han Dynasty (206BC-AD220), and the jade tablet might no longer have been required during ceremonial practices

Even more puzzling is a revised section of the painting on silk "Procession of Chariots and Horses" from the tomb of Lady Xin Zhui's son, Li Xi.

Spectral analyses revealed four large, clumsily added figures towering over a cavalry unit.

"Originally, this area showed chariots. Why these figures were painted over - and who they represent - remains a mystery," Yu said.

Modern magic

The latest discoveries owe much to cutting-edge technologies.

At a recent press conference, the Hunan Museum debuted a digital twin of Lady Xin Zhui's "ocher-yellow printed and painted silk robe," which is the earliest known example of combined textile printing and hand-painting.

Using AI, researchers reconstructed the robe's original vibrancy.

The garment, woven with twisting vines (printed) and blooming flowers (hand-painted), showcased the "no two petals alike" artistry of Han dyers.

"AI analyzed dye degradation patterns and filled in damaged areas pixel by pixel. It even simulated how the fabric draped on a body," He Ye, head of the museum's digital team, told the Global Times.

A second model replicated the robe's current weathered state, offering a side-by-side view of time's impact.

These tools are now being applied to reassemble fragmented silk texts and paintings.

"AI can identify ink types, match patterns and even predict missing pieces," Yu added. "It's like giving archaeologists a time machine."