ARTS / ART

Jackie Chan on kung fu spirit: AI can’t capture the art’s inherent soul

A living legacy

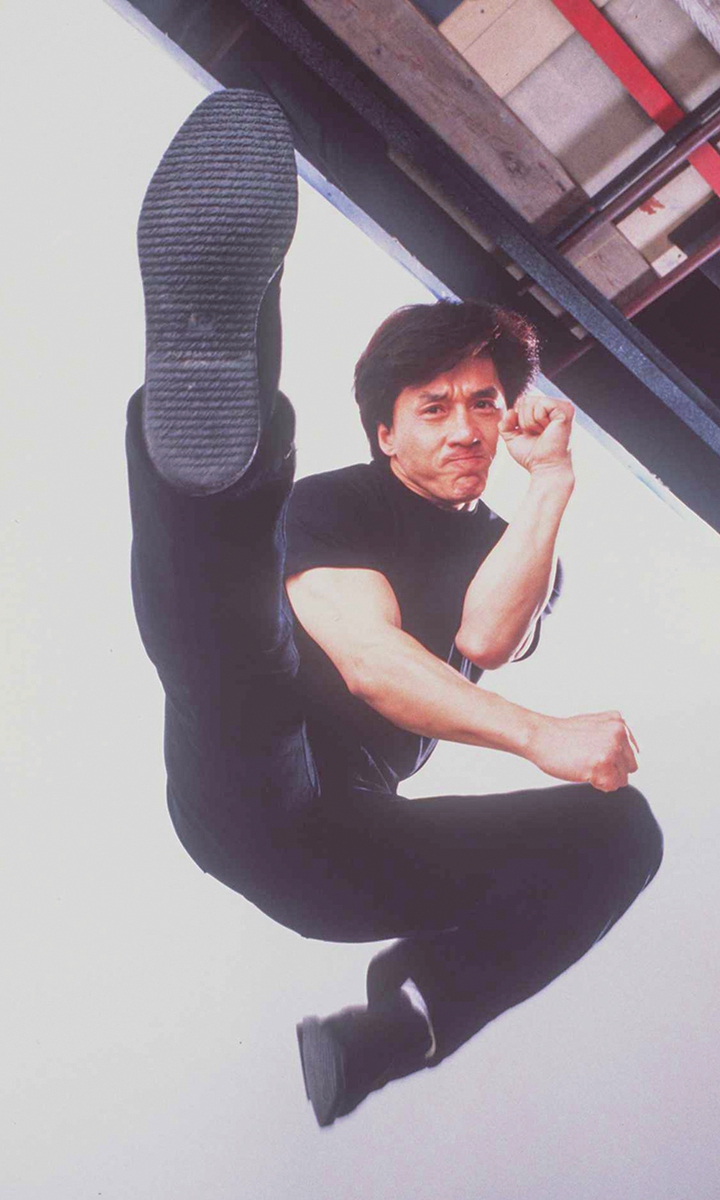

Jackie Chan stars in the movie SuperCop. Photo: VCG

For decades, Jackie Chan has been synonymous with kung fu film, blending acrobatic stunts, humor, and emotion to introduce Chinese martial arts to the world. In a recent interview with the Global Times, the global action icon delved into his understanding of kung fu's spiritual core, reflecting on its philosophical roots, the balance between tradition and modern technology, and the art of mentorship. Far more than a discussion of fight scenes, Chan's insights reveal a deep reverence for kung fu as a cultural language - one that transcends borders and generations.

A common origin

Chan begins by tracing the interconnectedness of martial arts traditions. His philosophy rejects rigid boundaries between styles.

"I've studied kung fu with Southern and Northern Chinese styles, as well as karate and aikido. But eventually you'll realize all these styles ultimately trace back to one source: Shaolin," he told the Global Times.

Chan points to Bruce Lee as a fusionist who created Jeet Kune Do by blending Wing Chun, a form of Southern Chinese kung fu, and a close-quarters system of self-defense, with boxing from the West.

"Styles rise through cultural momentum - Wing Chun gained global fame through films. But what about Northern Praying Mantis or Dragon Fist? They're equally profound, just less cinematic."

Chan said such combination proves that true mastery lies in synthesis, not separation.

For Chan, the diversity of styles serves a unified purpose: Cultivating discipline and virtue.

Central to this philosophy is the concept of "respecting those who teach you and appreciating those who help you."

In films like Karate Kid: Legends, where he plays master Han, Chan emphasizes that kung fu training is as much about character as it is about combat.

"Every style you learn is kung fu. Remember that kung fu is for protection, not aggression," he said.

This ethos echoes Confucian values of restraint and honor, distinguishing Chinese martial arts from mere physicality.

Such an inclusive view underpins Chan's belief that kung fu can bridge cultures, as seen in his films where Chinese techniques blend seamlessly with Western storytelling, emphasizing universal themes of courage and humility.

Navigate a tech-driven era

As the industry embraces AI and visual effects, Chan reflects on the evolving landscape of action movie.

"Today's actors are lucky," Chan admits, noting how technology allows for safer, more dynamic sequences.

"They can adjust angles digitally, so a punch doesn't need to land perfectly."

While praising AIGC's safety benefits, he also laments the erosion of hard-earned skills.

Chan said when young actors transition from singing and dancing into action roles, they just learn basics, such as stances, rolls, and jumps, but they can't replicate decades of discipline like him.

"Today, studios won't let stars risk injury … With AI, punches extend digitally, jumps are enhanced. I envy that safety … But if I'd had this technology back then, there would be no Jackie Chan that global audiences now know," Chan said, adding that true action stars are nearly extinct.

Jackie Chan stars in the movie SuperCop. Photo: VCG

"Audiences see Robert Downey Jr. in Iron Man and say, 'He acts well' - not 'He fights well,'" he said.

Chan's own career was defined by relentless physicality - stunts performed without doubles, injuries endured, and a work ethic forged in the crucible of 1970s Hong Kong film.

Yet Chan is no Luddite. He acknowledges the role of innovation in making action movie accessible to new generations, especially young actors like Ben Wang, who train briefly but benefit from modern tools.

But Chan emphasized that technology helps newcomers enter the field, but it can't replace the soul of kung fu.

He praises contemporary stars like Chinese actor Wu Jing and international peers like Tom Cruise for their commitment to authenticity, even as AIGC dominates.

For Chan, a true action star's credibility comes from showing up in person, sweating, and risking injury.

This tension between tradition and innovation mirrors Chan's approach to mentorship.

"You don't need a gym; any object can be a training tool," he says, recalling how he once used a door handle as a dumbbell.

This pragmatism, combined with Chan's signature humor, keeps kung fu relevant and relatable, proving that its essence lies not in spectacle, but in adaptability.

Passing the torch

For Chan, the most profound aspect of his journey is transitioning from student to mentor - a role he compares to his own teachers like Yuen Siu-tien, who guided him in Drunken Master, a 1978 Hong Kong martial arts comedy film.

"Sitting on set watching a young actor practice, I see myself decades ago," he says, adding that now he has become the master sharing the values of ritual, justice, integrity, and honor - not through lectures, but through how they move and interact on screen.

Chan's influence also reshaped many young actors including Ben Wang who acted as master Han's apprentice in the film Karate Kid: Legends.

Wang told the Global Times that as an American-raised Chinese, kung fu films kept him connected to his roots.

"I never lost the connection to Chinese culture and my Chinese roots because that was important to me. And Chinese martial arts are a big part of the culture that Chinese people are so proud of."

He shared martial arts are about defense, discipline, and cultural pride, and this film passes that torch.

The two stars show optimism about kung fu's global appeal, driven by its universal messages.

Chan explains that when a Western audience sees a master teaching a student to defend, not attack, they recognize that as a human value, not just a Chinese one.

This belief in shared humanity is what makes Chan's films resonate across continents - from the streets of Beijing to the backlots of Hollywood.

For Chan, true mastery isn't in the fist, but a spirit passed from teacher to student, generation to generation.