ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

How Chinese experts revive a lost weaving skill of textile cultural relics

Restoring a silk treasure

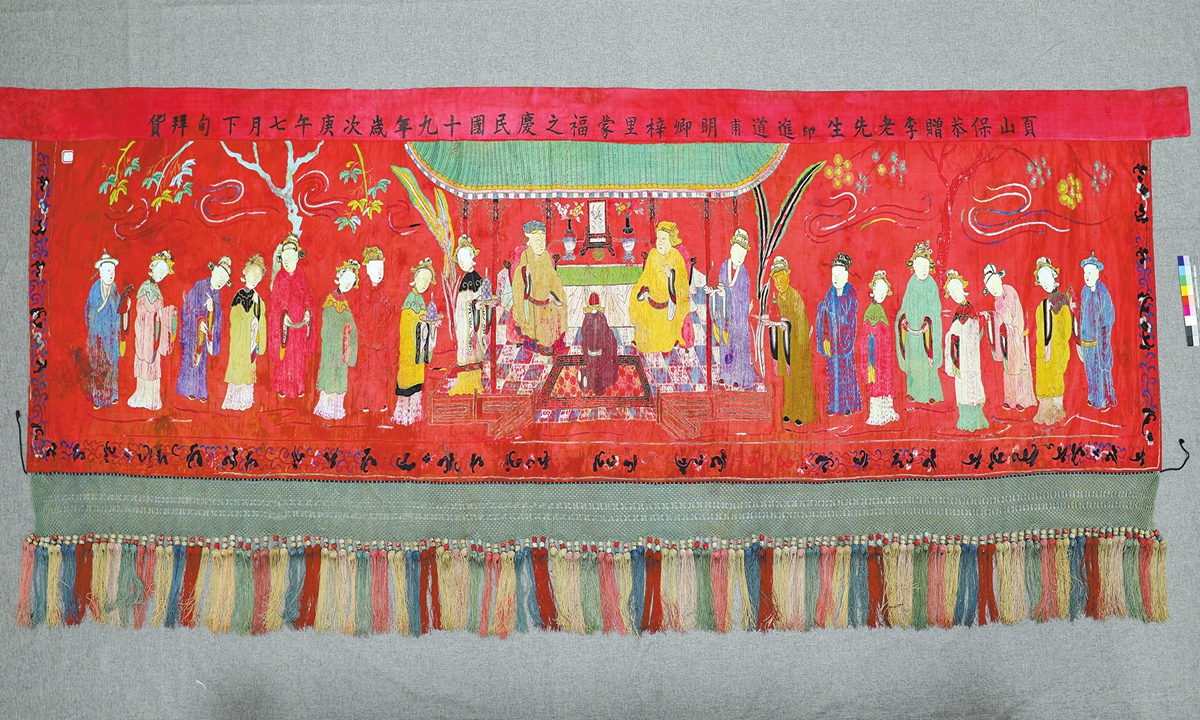

The silk embroidery of Guo Ziyi's birthday celebration

In a quiet corner in the Luonan County Museum, Northwest China's Shaanxi Province was once a piece of silk embroidery, with about 180 bits of damage and 39 missing tassels. Today, the piece is almost unrecognizable, fully restored after four years, thanks to Wang Dan and her team, a group of conservators with the patience of monks.The banner, a 3-meter long, 1.2-meter-wide stretch of red and gold embroidery commissioned for a birthday celebration nearly a century ago, lay in tatters, its colors faded and its tassels drooping like wilting flowers. Under the glow of a magnifying lamp, Wang traced the frayed threads with a fine needle, as if coaxing a dead past back to life.

"It's not just repairing a piece of cloth," Wang, an associate researcher at the Key Laboratory of Archaeological Sciences and Cultural Heritage at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), told the Global Times. "It's about reviving a story and the local folk customs."

Wang Dan Photos on this page: Courtesy of CASS

Threads of memoryThe textile is officially known as the "silk embroidery of Guo Ziyi's birthday celebration," a once-vibrant banner from a century ago. When it first arrived at the lab, it was a heartbreaking tangle of threads, stains and broken warp fibers so fragile they cracked at the lightest touch.

"The extent of the damage was overwhelming," Wang explained. The left side, spanning two meters, had suffered significant warp thread loss. "In textiles, the warp threads are fine and delicate, especially in satin fabrics like this one, where the silk threads are longer and more fragile."

What's more challenging is that the banner had clearly been reused and roughly repaired by previous owners using mismatched white and black cotton threads, creating distortions and misalignments. "It looked like someone had sewn it back together without any regard for precision," Wang noted.

To address the extensive damage, experts employed the "laid thread technique," adding a layer of mulberry silk backing fabric beneath the relic. This layer was carefully weakened in strength to avoid further stress while providing essential support. Then, by using laid thread stitches, conservators reconstructed the warp lines, mimicking the original warp threads and stabilizing the weft threads above.

"This method aligns with the international principle of 'consistent from afar, distinguishable up close,' ensuring both authenticity and stability," Wang emphasized. But the process also requires patience. "A thumb-sized bit of damage could have taken us up to a week to repair."

Piece by piece, Wang and her team designed a silk underlay, a subtle mesh that provided support without overshadowing the original.

However, the tassels were another conundrum: Weighted with cores of local mud - a clever trick to make them drape beautifully - but now cracked and crumbling. To restore them, Wang's team embarked on a research odyssey, combing through museum collections and old photographs to decode the unique double-twist knot that once gave them their signature elegance.

"No one documented it," she said. "It was an oral tradition. We had to learn it from scratch."

"To be honest, the 39 missing tassels were often considered optional in other textile restorations, but we still preferred to restore them as we aimed for a research-oriented, high-fidelity restoration that preserved the piece's integrity."

After extensive investigation, Wang's team found no exact matches. It took them a year of relentless experimentation, disassembling, reassembling, and often working behind closed doors before they successfully revived the ancient method.

For the team, the process is not just about restoration, but also a discovery of local customs and contribution to the understanding of social history.

One example lies within the process of tackling widespread contamination of the textile, where conservation experts employed an innovative approach by using composite bio-enzymes that work like targeted therapy in medicine. This technique avoided the secondary damage of water-based cleaning - such as color bleeding or water stains.

Surprisingly, analyses of these contaminants revealed food residues, offering insights into the dietary habits in southern Shaanxi at the time, as well as the lively celebratory scenes during birthday banquets. In the course of the restoration, experts had found multiple traces of paste used repeatedly to affix paper strips, highlighting yet another layer of social practices embedded in the artifact.

Promising future

Many of the textile artifacts and techniques in China are, in fact, at risk of being lost. In the past, traditional craftsmen generally did not document their skills.

"On the one hand, they had no concept of record-keeping; on the other hand, their craftsmanship was usually passed down orally and by demonstration," Wang Shujuan from the China National Silk Museum who revived the textile relics from the Huangsheng tomb of the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279), told the Global Times.

Thanks to the experts, many significant strides in textile cultural relic conservation have been made in recent years. A Tibetan golden crown from the Tang Dynasty (618-907) with a composite object containing a valuable textile component was restored, and currently, the lab is working on restoring a coat worn by Sun Yat-sen, a Chinese revolutionary and statesman.

Each textile relic presents unique problems. "Experts often combine traditional methods, like using pure silk as backing and delicate laid thread stitching, with scientific techniques," Wang said.

Wang emphasized the importance of balancing tradition and technology: "We believe that textile restoration should always begin with physical, mechanical methods, supported by modern science, rather than just defaulting to chemical polymers, which can accelerate the aging of and damage to the piece over time."

She acknowledged that this approach can be slow and labor-intensive - sometimes requiring tens of thousands of stitches on a single small hole - but it ensures the relic's longevity.

Through these efforts, Chinese textile conservators are not only preserving artifacts, but are also piecing together fragments of history - revealing clues about cultural practices, local craftsmanship, and even social customs.