ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

Honoring classics while being artistically open, pipa master Wu Yuxia takes Chinese melodies to world

Ancient notes, global echoes

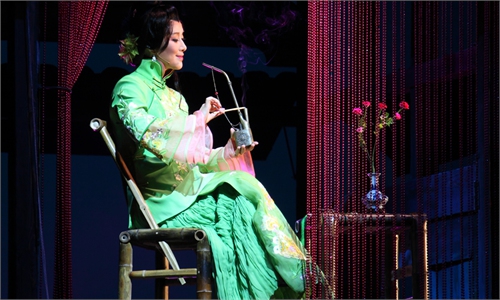

China's national first-class musician Wu Yuxia performs pipa at a concert Photo: Courtesy of Wu Yuxia

Once a little girl watching her teachers craft pipa fingernails with electric soldering irons and celluloid, 66-year-old Wu Yuxia now stands as China's national first-class musician, a virtuoso who has brought the more than 2,000-year-old traditional music instrument pipa to concert halls worldwide.

Born into an ordinary household in Shanghai's nongtang (the local's typical type of alleyway neighborhoods), Wu felt she had been "chosen" by pipa due to her natural talent and dexterity revealed when she was little. Yet after decades of advancing the instrument while pondering on Chinese traditional music's spirits, now, Wu not only chooses the pipa as a lifelong art career, but also as her voice to articulate China's cultural soul worldwide.

Starters work harder

The instrument of pipa is dubbed as the "King of the traditional Chinese musical instrument." In ancient times, the instrument made its way to China along the ancient silk road, and reached its artistic boom in China's Tang Dynasty (618-907).

As a young girl 50 years ago, Wu may not have fully understood such deep history of the pipa. But she felt an inexplicable pull toward the instrument. "I saw my little friends carrying the pipa around in nongtang, and I longed so much to become one of them," Wu told the Global Times.

Perhaps it was this heartfelt longing that led to Wu being selected by her teachers as a kid of musical potential.

Though barely in her teens, she had already encountered a "lifetime moment": in 1972, she performed for then US president Richard Nixon during his historic China visit, at the Shanghai stop of his journey.

"Back then, we had to wake at 5 am to practice, and the performance demanded absolute perfection, this was not easy for a child," said Wu.

Though the pipa master said she was "neither the brightest nor the prettiest girl" when little, her diligence has forged her solid pipa technical foundation. Now, among all the child performers for Nixon's visit, Wu is the only one who made the pipa her life-time vocation. Now, she is the president of the China Nationalities Orchestra Society, a member of the Artistic Creation Committee and a doctoral supervisor at the Chinese National Academy of Arts.

A cultural symbol

Driven by diligence, Wu left Shanghai and headed toward Beijing to further hone her music craft. She had blossomed into a young performer to bring Chinese music to the world in the late 1980s. Around that time, Wu had been invited to Japan, making history as one of the first traditional Chinese musicians to give solo recitals abroad.

Be it on stage or cocooning in her rehearsal room practicing day and night, Wu gradually realized that mastering Chinese traditional music demanded not just good techniques, but "an understanding of the Chinese cultural depth behind the instrument's notes."

The pipa's cultural depth lies in that it can convey "lyrical and martial aesthetic styles" (lit: wenwu qu) that are rooted in Chinese cultural and art aesthetics.

A pipa piece's "lyrical style" is known as "wenqu," which it characterized by emotive melodies, requiring the performer to use techniques depicting a character's inner thoughts or the scenery of beauty. Wu told the Global Times that Spring River Flower Moon Night is a typical "wenqu" since a performer has to use genteel plucking skills to portray a scene of a scholar's nocturnal contemplation under the pen of Tang Dynasty poet Zhang Ruoxu.

Drastically differing from literati elegance, pipa's martial style, or "wuqu," often depicts dramatic historical events and the epic story of heroes. In the music piece of Ambush from Ten Sides, Wu revealed that she would use the technique of scattering strums to depict the intense battlefield scenes. In another piece, the King Chu Doffs His Armor, the artist uses the rapid finger-rolling technique with deliberate tempo distortions and rhythmic disruptions to embody the inner turmoil between Xiang Yu and his concubine during their tragic parting.

"It's not just about making the instrument sound beautiful, but it's about embodying the classical Chinese spirits and aesthetic pursuits," Wu noted, adding that it is such cultural pursuits that separate instruments like the pipa from Western ones like the guitar. An artist might be using pipa to mimic guitar to perform, but the Chinese instrument's "innate expressive power remains irreplicable."

Open to global fusion

Carrying with pipa's "irreplicable aesthetics," Wu had taken the traditional instrument to numerous world stages. Other than the 1980s Japan visit, she had brought pipa performances to Vienna's Golden Hall, to the Carnegie Hall in the US as well as the United Nations General Assembly Building.

Wu said that through her performances, Chinese pipa can go beyond cultural difference to connect people.

Over the years, Wu inherited Chinese traditional musical legacy by not just spreading it, but making innovations integrating worldwide musical elements.

Taking inspirations from China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Wu has created a pipa piece that is called "Miaoyin Tianwu," roughly translated as "Dunhuang music and dance." The piece was inspired by Chinese Dunhuang murals but added with the percussion instrument Hang rooted in European culture. Wu told the Global Times that "fusion" is the main theme of this musical piece. This theme has also inspired her educational endeavors. "Through teaching, I aim to convey both theory and practice to students," said Wu.

"We can draw inspiration from other music cultures, like I myself also play jazz, as innovation is about respect, not to please any other musical culture," said Wu.