ARTS / BOOKS

Chinese writer Hu Xuewen: My roots and inspiration both grow on soil of countryside

Where wind carries stories

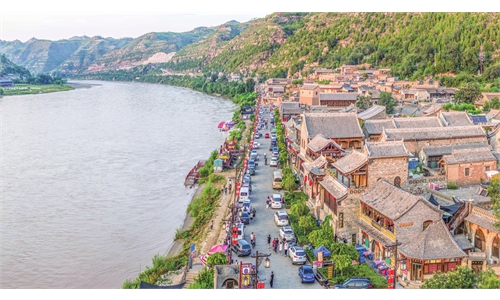

A rural scene of Hu Xuewen's hometown in Guyuan county, Hebei Province Photos on this page: Courtesy of Hu Xuewen

Unlike those writers who, in his words, "can be Borges - writing from a library," Chinese writer Hu Xuewen insists that he is a product of the land. Born and raised in the countryside in North China's Hebei Province, he writes about the countryside's flora and fauna as well as villagers, blending the magical realism with a rhythmic narrative, even going so far as to have a tornado sweep everything into the sky. For Hu, the act of writing is inseparable from memory and imagination.Hu's latest novel, once again grounded in the countryside, has ascended to the top 10 of the national new book charts in April 2025, with three printings in just over a month. In the eyes of critics, this is already quite a good achievement for a full-length novel writer.

Amid the flurry of cultural change brought about by short videos, web dramas, AI-generated writing, and online literature, does anyone still want to read rural literature? Hu remained optimistic in his interview with the Global Times. For him, rural literature contains the vibrant life experiences of generations of writers, which have been enriched by the passage of time.

The stories carried by the wind across the ridges of the fields will never cease.

Hu Xuewen

Pulse of the land"I write about the countryside not just because I know it," Hu told the Global Times, "but because every time I write about it, I feel a surge of passion and creativity." Even sitting at his desk, the writer can see the shape of the trees, smell the flowers, and feel the dew on a petal - whether it is a sunny or rainy day. These details live vividly in his mind.

With his life experiences in the village, Hu prefers to use the word "approaching" rather than "close" to describe the relationship between humans and nature in the countryside - sometimes it is familiarity, sometimes it is fear. "A snowstorm, a sandstorm - they can create a sense of threat and distance. Rural life is not just idyllic; it's filled with complexities," said Hu.

Such deep affection for the countryside and the meticulous observations are transformed into the words and reflections in Hu's works. The writer noted that material scarcity may have marked the past, but today China's rural area has undergone great changes. What interests him now is not just material conditions, but also its cultural life - the resilience, traditions, and desire for meaning.

This shift is evident in his novels such as Hope and Life (The Chinese title: You Sheng) and Longfeng Ge (lit: Song of Dragon and Phoenix). These works explore the transformation of the countryside and the changes of its people, often through the lens of several generations. In Longfeng Ge, for instance, Hu traces the fortunes of a family from the 1960s to the present, compressing a century of changes into the canvas of ordinary lives.

Reimagining rural stories

Meng Fanhua, noted Chinese literary critic, once wrote on the Farmer's Daily that the greatest achievement of Chinese literature in the past century lies in rural literature.

The works of renowned authors such as Mo Yan and Jia Pingwa depict both the courageous and passionate vitality of ancestors, and the simplicity and beauty of pastoral life, with the cultural lives of villagers serving as a key focus. Following the widespread dissemination of these rural-themed works, rural literature has become an important medium for urban readers to understand and imagine the essence of rural China, according to China Youth Daily.

In Hu's creation of rural literary works, he is keenly aware that nowadays, the "rural area" is no longer confined to the village. The stories of "larger rurality" - a term Hu uses to include spaces extending beyond the countryside to county town and even some cities - are just as compelling.

To improve the literary narrative of "larger rurality," Hu draws inspiration from music, paintings, even detective fiction. "Each novel is a new experiment in form as well as content. I am always looking for a sense of novelty - whether in the subject or the technique," said Hu.

In works like Hope and Life and Longfeng Ge, he interweaves elements of magical realism: A rural woman wanders in the village every night in her sleep or another villager is swept into the sky by a tornado, witnessing the world from above, farm tools and livestock swirling around her.

This blends the real and the surreal, the roughness of northern villages and the refinement of southern towns.

The writer has recognized that the challenges posed by fragmented reading habits and the allure of new media, but he believes good stories and memorable characters still matter. "Writing must be sincere - if you are not moved by your fiction yourself, how can you expect readers to be?"

For Hu, the future of rural writing depends not only on the persistence of the countryside experience, but also on its renewal. While he notes with some regret that many younger writers have not lived through the rural transformations he witnessed, he argues that "rurality" itself will not vanish.

"Rural culture, the culture of small towns and counties, will endure. What matters is how writers adjust their understanding of 'rural areas' and keep telling stories that reflect the ongoing fusion of tradition and modernity," the writer noted.

Hu's writing is a testament to how personal experience, creative passion, and aesthetic innovation can keep tradition alive in a rapidly changing society.

"Every writer has a literary map," Hu said. "A familiar region of life becomes the soil of their writing."