ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

At 93, 'Wushan Man' discoverer continues to unearth clues to China's ancient human origins

Never-ending quest

An aerial view of the Longgupo site in Wushan, Southwest China's Chongqing Municipality Photo: VCG

Wearing a dim headlamp, and often getting covered in mud while working in cramped caves, this is all in a day's work for Chinese archaeologist Huang Wanbo.

At 93, Huang defies the conventional image of a senior scholar devoted to desk work. Instead, he remains passionate about on-site excavations, patiently using a shovel and brush to uncover what he describes as the "yet-to-be-fully-revealed secret."

The "secret" to Huang lies in the Longgupo Site. Located in Wushan county, Southwest China's Chongqing Municipality, it is the earliest prehistoric site discovered to date in East Asia with 2 to 2.5 million years of history.

Forty years ago, Huang unearthed a broad bean-sized animal tooth here, unveiling the mystery of the "Wushan Man." His explorations at the site continue unabated, and the most recent round of excavation under his direction has just yielded fresh findings.

Huang Wanbo Photo: Courtesy of Huang Wanbo

'Piecing clues together'

To date, Longgupo has undergone five rounds of archaeological excavation. The latest round, initiated in 2023, recently announced its findings. Such findings include the fossilized feces of Homotherium, or saber-toothed tiger, and the remains of tools made from animal bones by ancient creatures.

These discoveries might sound unrelated, but Huang explains they are "clues that can be pieced together" to depict the evolutionary features of Wushan Man.

"The animal bones showing cut marks are likely to prove ancient creatures' use of tools," Huang told the Global Times.

The Wushan Man refers to a highly evolved primate and a subspecies of homo erectus. Its name was given after 1985, when Huang discovered the fossilized mandible of an ancient creature at the Longgupo site. The fossil contained two molars. This piece, like a key, unlocked the treasure-trove-like site's other excavations.

Following the first excavation from 1985 to 1988, the site underwent four additional excavation phases between 1997 and 2024. In addition to the discovery of over 3,000 stone tools, three ancient creatures' incisors and the special "living surfaces" were also found.

A living surface resembles "the appearance of how bones are arranged on a dining table after people have eaten ribs," Huang explained to the Global Times. The Longgupo site's most special living surface was filled with forelimbs and hindlimbs of large animals. Also, these remains all belonged to elderly and young animal individuals.

Huang was struck with awe by this scene as it revealed the Wushan Man's incredibly economic hunting wisdom. At that time, when they hunted large animals, they chose to bring back the most tender and meaty limbs to their dwelling caves to conserve energy.

The wisdom of the Wushan Man extended far beyond hunting, as they had already mastered the art of surviving in harmony with nature. The site of Longgupo was a secluded karst basin and is enclosed by mountains.

This natural enclosure provided a good habitat with a degree of concealment. Meanwhile, sinkholes within the basin ensured a reliable water source for the inhabitants and nurtured lush vegetation.

Taking all excavation results into account, Huang was able to thread the life picture of the ancient creature. "Every dawn, they would appear near water sources and foraging grounds, hunting large game with simple stone tools, and dragging their prey back to the cave to share with their companions," said Huang.

The moment Huang saw the tooth fossil of Wushan Man with his own eyes, the expert began to believe they were not apes but early humans.

Although this theory still requires more evidence, if confirmed, it would "bring a completely new perspective to the known theory of human origins," Huang noted.

"If we can prove that the Wushan Man was indeed human, then the trail of human origins in East Asia could be traced back to 2 to 2.5 million years ago. This would be much earlier than the prevailing timeline suggested by the 'Out of Africa' theory," Huang noted. He added that his next step is to continue deeper excavation, to "find more bones, and to find more evidence of humans."

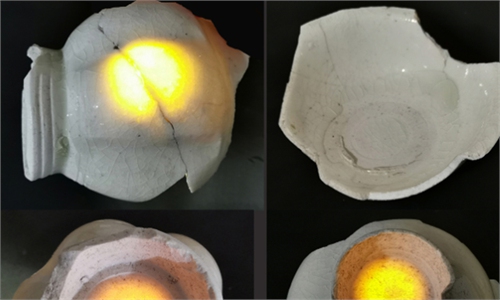

Bones excavated by the archeologists in 2004 at the Longgupo site in Wushan, Southwest China's Chongqing Municipality Photo: Courtesy of Huang Wanbo

'Skill, luck and timing'

Having devoted over seven decades to paleoanthropologic research, Huang is not only the discoverer of the Wushan Man but also a key figure in the discoveries of the "Hexian Man" in Anhui Province and the "Lantian Man" in Shaanxi Province.

In 1980, Huang traveled to Hexian county, East China's Anhui Province, where he unearthed a skull fossil of ancient ape man from the local soil dating back 412,000 years.

His excavation of the Lantian Man in Shaanxi Province was even a better illustration of why archaeological work is always a pursuit where skill intersects with intuition.

In 1963, in Lantian, Huang spotted a piece of bone in a gully on the Loess Plateau. While his companions dismissed it as a relatively recent relic from the Neolithic Age, Huang, relying on his intuition, insisted on excavating it. It was precisely this persistence that led to the discovery of the Lantian Man's jawbone, dated to 1.15 million years ago.

"Archaeology hinges on three things: Skill, luck, and timing. But all of them rest upon one's mastery of the basics," Huang told the Global Times.

Though now a veteran scholar, Huang said that his entry into archaeology had "an unplanned start" when he was a young man.

After being assigned to the field through a job placement, he was first introduced to palaeoanthropology. On his very first night at work, while in an office, he opened a cabinet to look for something— and found himself face to face with a human skull.

This experience, despite sending a shiver down his spine, gave him a clear understanding of his profession.

His career was further shaped by the mentorship of Pei Wenzhong, the celebrated Chinese paleoanthropologist who discovered the skull of "Peking Man."

"It was from him that I witnessed the rigor and passion a researcher must possess, which will forever inspire my work," Huang said.