ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

From Li Bai to 'Satantango,' translation carries Chinese and Hungarian cultures across continents

Poetic bonds

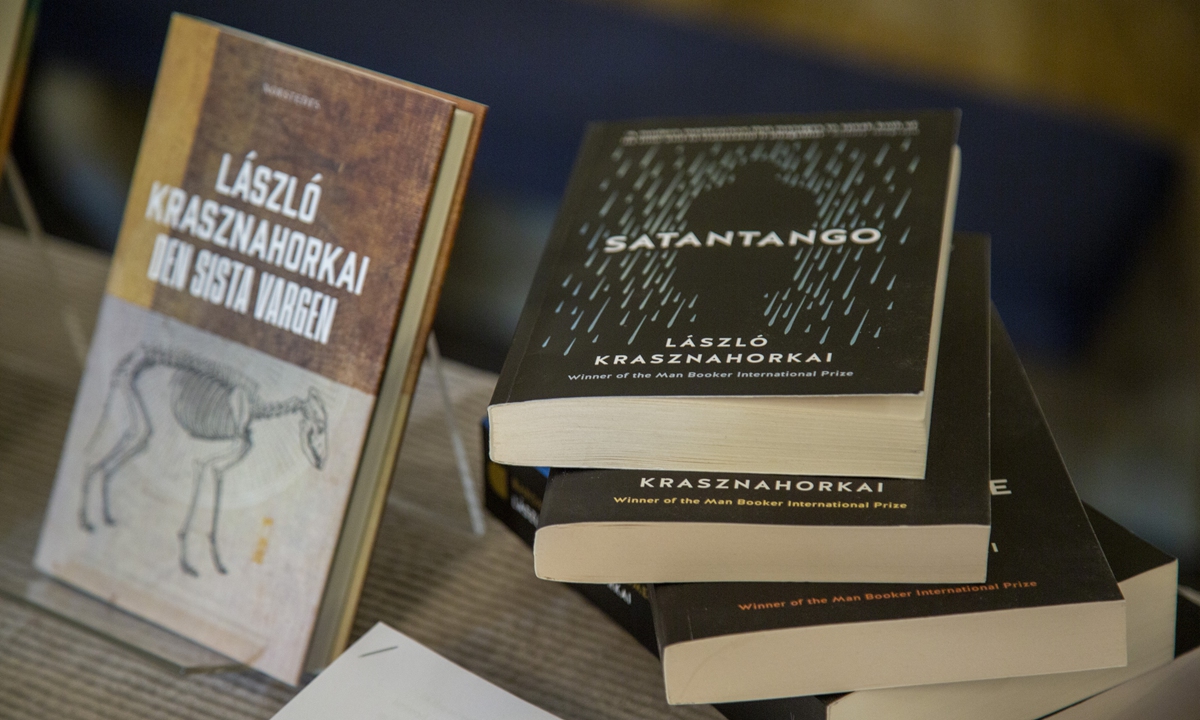

The published works of Hungarian writer Laszlo Krasznahorkai Photo: IC

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to Hungarian writer Laszlo Krasznahorkai. The news quickly sent his signature novels, Satantango and The Melancholy of Resistance, to the top of China's online reading charts.

Yet, for many Chinese readers, the first thing that captivated them upon opening Satantango was not the story itself, but the witty and heartfelt translator's preface, penned by the esteemed writer and translator Yu Zemin.

Yu, reflecting on Krasznahorkai's win, said he was not surprised. He told the Global Times that the Hungarian author's works display profound philosophical reflections on humanity and human nature, coupled with a striking originality in form.

"As a writer, he is tenacious and persistent, having spent 40 years exploring a single central theme in-depth. These three qualities meet the criteria of any major literary award," Yu said.

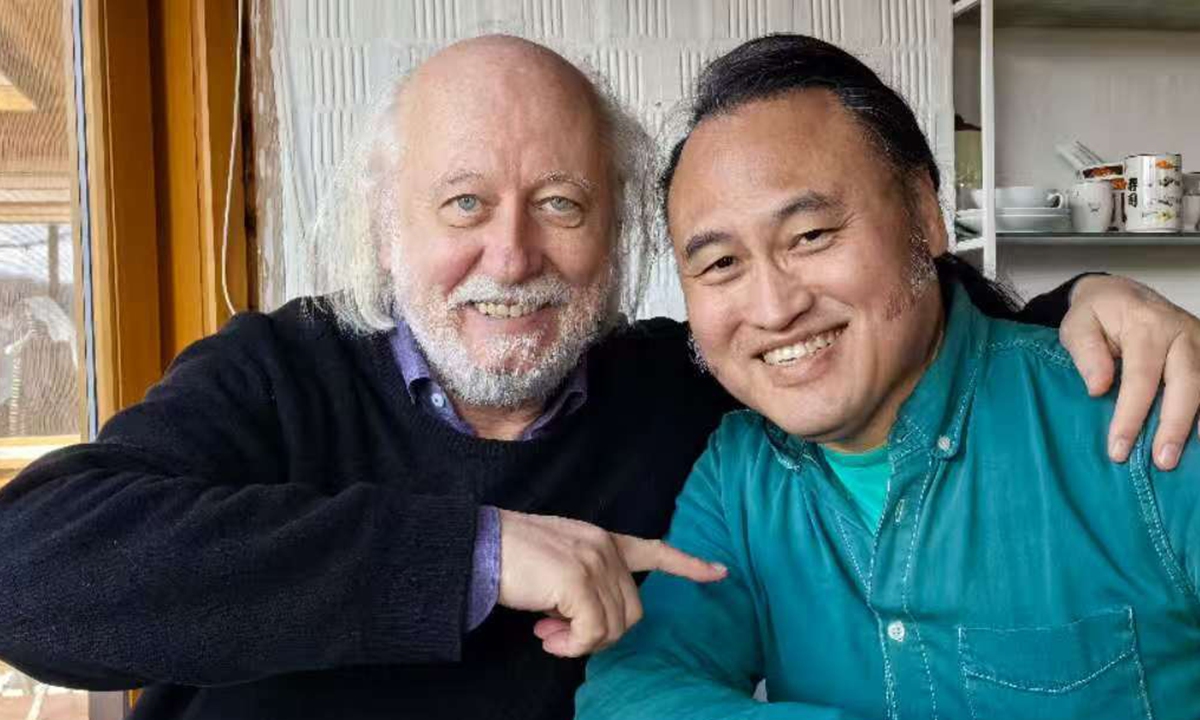

Yu and Krasznahorkai first met in the early spring of 1993. Their friendship grew rapidly, thanks in part to a mutual admiration for the Chinese poet Li Bai from the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and his verses.

Over the past three decades, they have become close friends. Yu is well aware of Krasznahorkai's deep fascination and love for Chinese culture.

In 1998, the two even set out together on a journey across China in search of traces of Li Bai. Krasznahorkai traveled with a collection of Li Bai's poems and often steered conversations back to the poet: "Do you know who Li Bai is? Can you recite his poems? Why do you like Li Bai? Have you heard any legends about him?"

Yu credited Krasznahorkai's passion for Chinese classical poetry and culture to the art of literary translation.

"We should be grateful to those Hungarian translators of the 20th century who introduced Li Bai's poetry to Hungary. That was the beginning of Krasznahorkai's understanding of China and Chinese literature," Yu explained. "That's why I always said translation has the power to take people on a journey of a thousand miles without leaving their homes. Through translated words, we can imagine distant worlds."

Now, the baton has been passed to Yu and his generation of translators.

Through their work, they are building bridges and offering platforms for Chinese and Hungarian literature to gaze at each other, providing readers in both countries with a telescope through which to look across the cultural divide.

Laszlo Krasznahorkai (left) and Yu Zemin Photo: Courtesy of Yu Zemin

Joy of challenge

Yu described the process of translating Krasznahorkai's Satantango as a heroic struggle, much like a woodworm gnawing through a stone beam—arduous, relentless, yet ultimately fulfilling.

"The entire novel is comprised of viscous, convoluted sentences that flow like molten lava, with barely a paragraph break," Yu recalled. However, Yu believes that readers who persevere to the end will experience a unique sense of accomplishment.

"It's like the thrill of bungee jumping, overcoming the challenge brings a sense of release and liberation," he said. "The story's slow pace is like a strong, mellow wine; once you adapt to his narrative rhythm and tone, you will find yourself increasingly savoring the experience, and the pleasure of unraveling the text grows as you read."

Yu first encountered the story of Satantango in 1993 through its seven-hour film adaptation.

Many years later, he read the original novel, and it was only after another two decades that he was able to translate it into Chinese and introduce it to Chinese readers.

This long period allowed Yu to deepen his understanding of the book. Media like film, as well as discussions with the author himself, gave Yu a more three-dimensional grasp of the work's tempo and mood, which greatly helped during translation.

"Communicating with the author is crucial for truly understanding the work," Yu told the Global Times.

He noted that knowing what mood the author was in when writing, and how the story connects with his life, allows a translator to gain a more layered understanding and makes it easier to grasp the essence of the work.

Krasznahorkai's writing is characterized by sprawling sentences and a slow, deliberate pace, which poses a real challenge for readers. Despite the difficulties, Yu believed that once translated into Chinese, the text would become much more accessible.

"As long as readers have patience, understanding, and a willingness to take on the challenge, they will feel the thrill of overcoming reading difficulties," Yu explained.

The Chinese version of Satantango Photo: Courtesy of Yilin Press

A Chinese bond

Krasznahorkai has a Chinese name, "Hao Qiu," bestowed on him by an elderly Hungarian sinologist. The name means "beautiful hill" and also pays tribute to Confucius through the character "Qiu." "You can see his affection for Chinese culture even in the name he chose," Yu said.

In 1991, Krasznahorkai visited China as a journalist and soon became enthralled by Chinese culture. He went so far as to have his whole family eat with chopsticks, dine out at Chinese restaurants, and listen to Peking Opera at home.

According to Yu, Krasznahorkai especially loves ancient China, reads the Chinese classic Dao De Jing, or The Classic of the Way and Virtue, and is captivated by Li Bai. In 1998, Yu accompanied him in tracing Li's footsteps through nearly 10 Chinese cities. Krasznahorkai admires Li's boldness, his celebrations of wine, the moon, life, separation and friendship.

Krasznahorkai's deep ties to Chinese culture owe much to Hungarian translators of the 20th century, who rendered the poetry of Li Bai and other great Tang Dynasty poets into Hungarian.

It was through these works that Krasznahorkai constructed a romantic, idealized vision of China in his mind. "To him, Li Bai is like a modern poet, his verses are abstract and imbued with natural grandeur," Yu said.

"Before Krasznahorkai ever set foot in China, he already possessed a 'telescope' that allowed him to gaze across a thousand miles. He fell in love with Chinese classical culture through literary translation," Yu noted.

"There are now more than a dozen Hungarian versions of the Dao De Jing. The cultures of China and Hungary have been linked together by translation."