ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

Multidisciplinary science unlocks 2,200-year-old secret on Qinghai-Xizang Plateau

Decoding a myth

The location of the Garitang Engraved Stone on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau Photo: Courtesy of the National Cultural Heritage Administration

Editor's Note:Perched on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau, a stone has captivated scholars by reshaping the narrative of early Chinese history. The Garitang Keshi, which can be translated as "Garitang Engraved Stone," has been identified as an authentic relic of the Qin Dynasty (221BC-206BC). It records an imperial mission by Emperor Qinshihuang, who unified China for the first time, to seek the elixir of life from the mythical Kunlun Mountains. Scholars highlight the stone as a geographic anchor that places the legendary "Kunlun" near the source region of the Yellow River, making it irrefutable proof of the exchanges between the Central Plains and the plateau over 2,200 years ago. This series will illuminate how this stone embodies the interconnected nature of Chinese culture shaped by ethnic exchanges, decode the multidisciplinary science behind the find, and explore the evolving legend of the Kunlun myth. This second part of the trilogy attempts to shine a light on archaeological exploration and research, and reveal how the secrets of this stone were revealed.

Archaeologists work at the site of the Garitang Engraved Stone in Maduo county, Northwest China's Qinghai Province. Photo: Courtesy of the National Cultural Heritage Administration

In 210 BC, a group of envoys led by an official named Yi, set off from Xianyang - the capital of the Qin Dynasty in present-day Shaanxi Province - on a mission to gather medicinal herbs for Emperor Qinshihuang. Their destination was the legendary Kunlun Mountains, a sacred land in their minds. After at least two months of arduous travel, the group arrived at the northern shore of Gyaring Lake in what is today Maduo county, Qinghai Province. There, on a wind-sheltered rocky outcrop facing the water and backed by a mountain, at an altitude of 4,306 meters, they came to a halt. Then they used flat-edged tools to carve 37 characters into the quartz sandstone, recording their mission to Kunlun.This is not a legend but an archaeological fact based on extensive investigations and multidisciplinary analyses of the engraved stone known as the Garitang Keshi, or Garitang Engraved Stone.

Today, as the wind sweeps across the banks of Gyaring Lake on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau, this stone inscription, dormant for over 2,200 years, has finally "awakened," sparking a rare academic debate in recent years. How was this stone confirmed to be an actual relic of the Qin Dynasty? How was the possibility of later imitation ruled out? These questions hung over the Chinese archaeological community like a persistent fog, refusing to dissipate.

Clarity finally arrived at a press conference held by China's National Cultural Heritage Administration on September 15. There, experts presented a "combination punch" of scientific methods, constructing irrefutable evidence of the engraved stone's authenticity. Using an interdisciplinary array of techniques, they studied the inscription's content, the composition of the stone, the surrounding environment and historical records, thereby confirming key details about the herbal mission: its purpose, route and participants. These methods also revealed the secret of how the inscription's characters have survived for millennia.

Zhao Chao, a researcher at the Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said the scientific authentication of this relic is not just a singular achievement - it marks the advent of a new paradigm in China for stone artifact verification. He noted that for the first time, a single ancient inscription has been systematically dated and authenticated through comprehensive scientific means, the Xinhua News Agency reported.

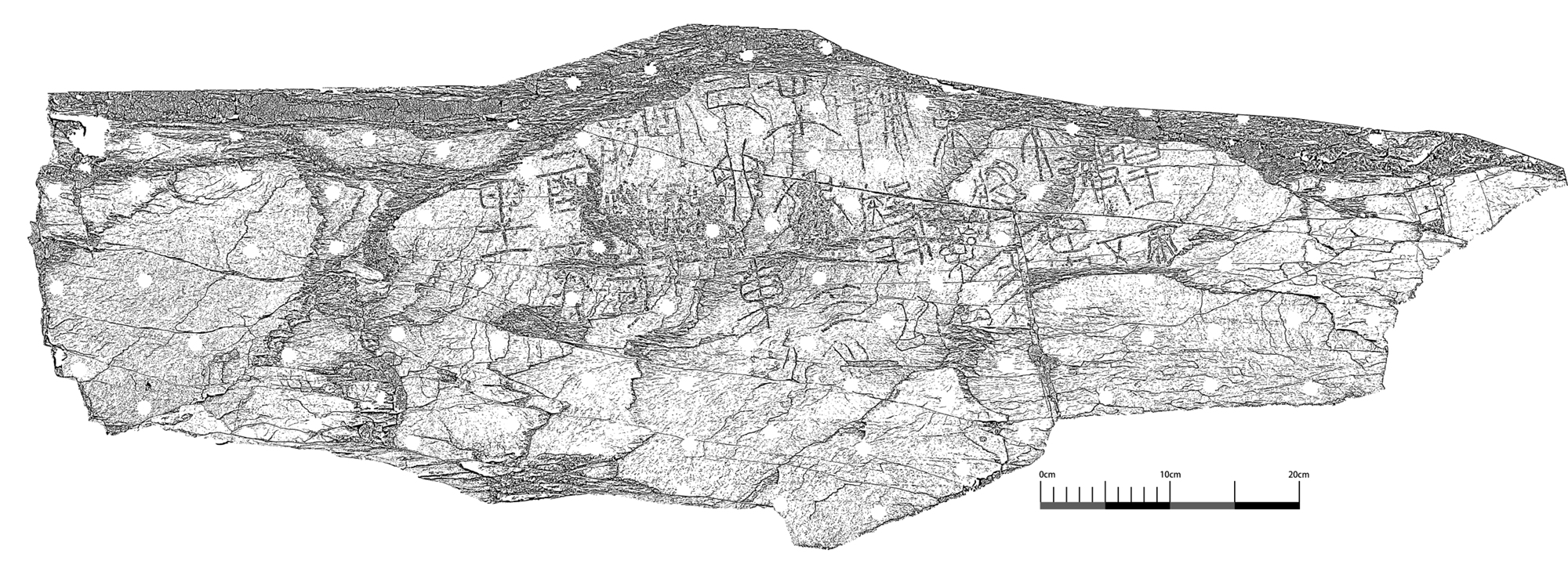

High-definition digital line drawing of the Garitang Engraved Stone Photo: Courtesy of the National Cultural Heritage Administration

Power of technologyThe 37-character Qin script stone inscription, measuring about 0.16 square meters, has drawn together experts from fields as diverse as stone relic conservation, Qin-Han archaeology, classical literature and calligraphy. The foremost question demanding an answer, and of central concern to academic and public discourse, was the precise meaning of the characters inscribed on the stone.

To obtain detailed information, the team has employed high-precision information enhancement technology, which allows for the digital acquisition of the artifact's imagery, ornamentation and inscription, without any physical contact or damage. By analyzing and processing the collected data, the clarity of the original surface was improved by 40 percent to 90 percent, according to Li Li, a vice president of the Chinese Academy of Cultural Heritage, who conducted the technical research at the site.

With the enhanced clarity, previous interpretations of the text were corrected. For example, a time reference in the inscription was initially read as the Chinese character "six," but on closer examination, a vertical stroke previously thought to be part of the character was actually the edge of a flaked-off rock surface, not a carved line. Thus, the character should actually be read as "seven."

After confirming the content of the inscription, experts faced a next challenge: How were these characters carved, and could they have been imitated by later generations? During the field investigations, experts like Zhang Jianlin, a researcher at the Shaanxi Academy of Archaeology, and Huo Wei, the academic dean of Sichuan University's School of History and Culture, noticed crucial details thanks to their years of professional experience. For instance, they observed that rock patina had penetrated deep into the carved strokes - something that could only have formed over a long period, not overnight. Their "discerning eyes" were complemented by modern technology, which provided quantitative and scientific confirmation.

Li noted that the team had used macro photography to document the features of the carved strokes and then conducted statistical analyses of their depth, width and cross-sectional area. The results showed the grooves were uniformly wide, with irregular chipping along the edges and flat-bottomed incisions. About 80 percent of the strokes showed clear signs of the resistance met during carving, confirming the use of flat-edged tools inserted diagonally into the stone.

Additionally, the team used portable fluorescence spectrometry to compare elemental composition within and outside the inscribed area. They found only slight differences, with silicon and aluminum accounting for 80 percent of the main elements. Notably, there was no trace of tungsten, cobalt, or other metals associated with modern alloy tools, excluding the possibility of recent forgery.

After this initial assessment of carving techniques, archaeologists proceeded to a second level of authentication. They used automated mineral analysis under electron microscopy to evaluate weathering patterns and surface composition.

"For stone artifacts, unlike wooden ones, we can't use carbon-14 to determine the degree of weathering or the era, since stone is inorganic," explained Liu Yong, a researcher with the Science and Technology Archaeology Department of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. "Instead, we take a tiny sample from the carved surface, add reagents and analyze its composition under an electron microscope."

For this inscribed stone, the stratification of the surface was analyzed, the migration of tin content was observed and the degree of aging in the carved grooves was examined to assess structural characteristics, Liu noted.

Over 2,200 years ago, the carriages of the Qin Dynasty pushed westward in search of the sacred mountains and mythical herbs. Today, scholars from many disciplines converged on the headwaters of the Yellow River, seeking the historical truth behind the Garitang Keshi. To uncover this truth, they have applied a diverse toolkit of scientific methods, each complementing the others. Chemical and surface analyses form one part of the puzzle; historical documents, contextual research, and interpretation of the inscription itself are just as indispensable. Together, they have formed a closed chain of evidence.

Millennia of protection

"When I stood before the inscribed stone, I was deeply moved. Towering on the shore of Gyaring Lake on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau and bearing Qin seal script, this stone made me feel the powerful vitality of Chinese civilization. It is hard to imagine the determination and perseverance of the herbalist team that trekked into the frigid, oxygen-starved heart of the plateau over two millennia ago," reflected Li Jiyuan, a deputy research fellow at the Qinghai Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology who has visited the site four times.

Having borne witness to the vitality of Chinese civilization for thousands of years, the question now is how to preserve this stone amid the harsh, high-altitude climate for the next millennium or more millennia - a crucial issue facing experts today.

The local government has implemented strictest on-site protection measures for the stone. Protective fencing and electronic surveillance have also been set up, and dedicated personnel are stationed on site around the clock, overcoming challenges such as low temperatures, lack of water or electricity, and no communication signals, to ensure 24-hour protection of the stone.

"The greatest threat to stone artifacts is weathering," said Chen Jiachang, a researcher at the China Cultural Heritage Institute. "This is a major challenge worldwide. Most methods seek only to slow down weathering, not to stop it completely."

A most direct, but also the most expensive, solution is to "build a house" over the relic, shielding it entirely from the elements. More common approaches involve weatherproofing materials, often silicon-based consolidants that form a protective film.

"In China, we frequently use polysiloxane," Chen explained. "It's colorless, transparent, hydrophobic and long-lasting, and it protects the artifact without harming it."

But what about large stone relics that must remain exposed, such as rock-cut temples or the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, Gansu Province?

"Many people think the Mogao Caves' arid climate prevents microbial growth," Chen noted. "But historically, extreme rainfall would seep into caves with thin ceilings, triggering microbial outbreaks." He joked that microbes thrive on carbohydrates and need nitrogen. "It's like ordering a bowl of beef noodles and adding an egg."

Yet microbes can also serve as protectors rather than threats. With microbial mineralization reinforcement, researchers can induce microbes to deposit stabilizing minerals onto fragile surfaces. Archaeologist Liu Hanlong from Chongqing University has applied this technology to stone relics, earthen sites and portable artifacts. The method offers high reinforcement strength, weather resistance and environmental compatibility, and has already yielded promising results at sites like the Dazu Rock Carvings.

Ultimately, Chen emphasized, the guiding principle of conservation should be preventive protection rather than emergency rescue. From digitizing the murals of Dunhuang to deploying high-precision imaging for the Garitang Keshi, early digital preservation ensures that artifacts - and the history engraved on them - remain accessible for future generations.

"For natural materials, deterioration is almost inevitable," Chen acknowledged. "Only by collecting and preserving these relics digitally in advance can we ensure that more generations can see our cultural heritage and understand our history."