Chinese sculptor Wu Weishan Photo: Chen Tao/GT

Editor's Note:

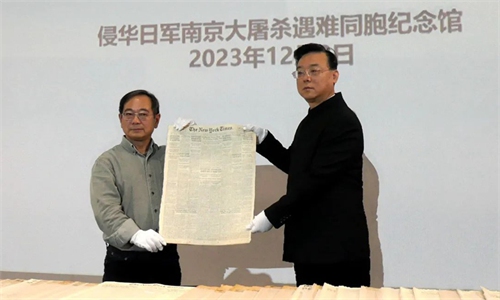

As China prepares to commemorate on Saturday the National Memorial Day for Nanjing Massacre Victims, internationally acclaimed sculptor Wu Weishan (Wu) has donated the precious drafts of his landmark theme sculptures for the expansion project of the Memorial Hall for Victims of the Nanjing Massacre by Japanese Invaders to the memorial hall itself. In an exclusive interview with Global Times (GT) reporters Li Qian, Zhang Ni and Liu Yating, Wu shared his emotional journey of creating these works as a tribute to the Nanjing Massacre victims and a call for justice and peace. Wu is also vice chairman of the Central Committee of the China Democratic League, and vice chairman of the China Artists Association.

The sculpture titled Family Ruined by Wu Weishan at the Memorial Hall of the Victims in Nanjing Massacre by Japanese Invaders Photo: VCG

'I want to revive their souls and let the world know this history'

GT: In 2007, the memorial sculptures you created for the Nanjing museum drew widespread attention. Eighteen years later, what motivated you to donate the original drafts?

Wu: In the 1980s, when I studied in Nanjing, the city's history left a profound impact on me. The memory of the Nanjing Massacre was etched into my heart. Whether as a student or later as a faculty member, I often visited the memorial to pay tribute to the victims. The astounding number of casualties displayed at the entrance to the memorial shocked me, but even more haunting were the exhibits: cremation barrels, skulls, and bullet holes in bodies - the eternal reminders of collective agony.

In 2005, I was tasked with creating theme sculptures for the museum's expansion. I knew this mission, rooted in history, was of immense significance. Thus, I resolved to portray the suffering of the victims, especially their state during the massacre, to revive their souls and let them converse with people living in peace today, as well as to inform the world of this sad history. During the creative process, I produced over 200 drafts and hundreds of figures, reconstructing the scenes. Due to space constraints in the museum, only the most representative works could be enlarged and cast in bronze for display. Now, with the support of the museum and colleagues from the Nanjing University Sculpture Art Research Institute, these sculptures are prominently exhibited in key areas. My accompanying texts are also engraved on the bases, with shadows cast on the white walls under the light - like historical imprints, eternal memories.

Donating the drafts was a decision I made years ago. Many were stored in my studio, but some were lost during moves. This time, I cast the remaining drafts in bronze and donated them to the memorial hall, to allow more people to witness and feel that history. As sculptors, we have a responsibility to present ironclad historical facts through art. Today, the souls of those who suffered during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1931-45) and the Nanjing Massacre may find solace in the afterlife, having known that China now possesses the strength of justice to counter the lingering specter of Japanese militarism.

GT: This year marks the 80th anniversary of the Victory in the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War. With Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi making erroneous remarks about Taiwan and the rising right-wing nationalism in Japan, how do you view the importance of remembering the Nanjing Massacre and history?

Wu: The direction of human progress should be peace and prosperity, so all militaristic actions will ultimately be terminated by justice. But this does not mean we can forget the history or remain silent. The Nanjing Massacre was one of the most tragic events of WWII, and as the Chinese people who suffered deeply, we have the responsibility and duty to disclose this history to the world, refuting rumors and falsehoods with ironclad facts.

The number of sculptures in front of the memorial is limited, and their scale is modest, but behind these limited works lies a profound national memory and a painful history. By donating these drafts today, as a Chinese citizen, an artist, and a creator who has erected over 60 sculptures in more than 30 countries and regions, I am sending China's voice of justice to the world. I hope that through more artistic creations based on the original images of the refugees and the victims, the public will remember history more deeply. The greatest power of this memory is the call for justice and peace.

A draft for the sculptures titled Refugees by Wu Weishan Photo: Chen Tao/GT

'Art that exposes ugliness and upholds justice resonates globally'

GT: What was your creative process like for these sculptures?

Wu: Sculpture can flexibly express and present the soul, embodying values. But what to sculpt and how to sculpt it is crucial. Especially for works permanently displayed in the memorial, they must help visitors understand the history, act as the warnings for the future, and prevent the tragedies and the resurgence of militarism. I felt it was essential to depict the tragic fate of unarmed Chinese people under the iron heel of Japanese militarism. For this, I researched extensively and interviewed many massacre survivors.

I created three groups of sculptures. The first, Family Ruined, is the central piece: a mother holding her dead child. Initially, I also made a figure of a husband being buried alive, with his hands and feet sticking out of the soil. But later, I felt that focusing solely on the grief-stricken mother and child could convey the theme more succinctly and powerfully, with the rest explained through text: "The slaughtered son will never return, the buried husband will never return." The second group, Refugees, depicts unarmed civilians fleeing. Among them are those with blown-off legs, corpses carried by relatives after they had been killed, women who jumped into wells after being raped, people carrying belongings to escape, the dying, and infants frozen to death while clinging to their mothers' breasts in winter… They could have lived peaceful lives, got married, worked, and thrived, but they lost their lives under the boots and blades of Japanese militarism, trampled like grass. The historical records I read often gave me nightmares. While creating Refugees, I felt as if I could converse with the victims' souls, vividly portraying their states, expressions, and movements during their escape.

The third group, Screams of the Souls, is a 12-meter-high sculpture at the memorial's entrance. It features a split mountain peak, with a hand emerging from the crevice, pointing forcefully toward the sky. This symbolizes the desperate yet powerful cry of a weakened China, trampled by Japanese invaders.

GT: How did you balance historical authenticity and artistic expression while creating these works?

Wu: Historical truth is the foundation of my creations. Before sculpting, I visited the memorial multiple times, each visit leaving a deep impact. The remnants of our slaughtered compatriots made me feel the blood of the Chinese flowing under the butcher's knives of the Japanese invaders. Their voices seemed to call out, urging the literature and art to profoundly portray and revive their souls.

But art must present the essence of the soul through form, often requiring sublimation and refinement.

For example, in Refugees, while depicting escapees, I emphasized human nature. Under Japanese militarism, unarmed civilians fled in panic. Photos and videos can show parts of the scenes, but sculpture demands stronger expressiveness. Thus, I used exaggerated postures - bodies leaning forward, hands trembling, mouths agape in extreme fear - to convey the refugees' inner terror. One piece shows an 80-year-old grandfather holding his 3-month-old grandson in his hands who was killed by Japanese soldiers. The child's body, frozen in the coldest December, became as stiff as wood. The grandfather, wrapping the child in cloth, held him with hands that trembled - not just physically, but with the despair and heartbreak of losing his lineage.

Art must capture such emotions. Importantly, such artistic expression is not fictional but grounded in history, current affairs, national sentiment, and the people's cries.

GT: As a world-class artist, your works are widely recognized overseas. Why do you think this series resonates with global audiences?

Wu: Many renowned scholars, including the late Nobel laureate Chen Ning Yang, who visited my Nanjing studio during the creation process, were moved to tears upon seeing the designs. Yang later attended the unveiling ceremony, standing in the cold wind, tears streaming as he said, "Seeing these tragic sights, I heard the bombings of Japanese planes…"

After the installation, many foreign visitors, including ambassadors from Germany and France , came to see them.

Models of the statues were exhibited at the Russian Academy of Arts, where they were permanently collected. The academy's president praised their astonishing power in conveying justice. These sculptures were also included in children's textbooks in South Korea and became widely known. In 2012, they were temporarily displayed at the UN Headquarters and praised by then UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon.

Today, these sculptures have spread across nations, proving that human destinies are interconnected. Art that exposes ugliness and upholds justice will find global understanding and resonance. While form and style matter, what's most important is the sculpture's embodiment of humanity's longing for peace, justice, and condemnation of the evil.

A draft for the sculptures titled Refugees by Wu Weishan Photo: Chen Tao/GT

'Sculpting for magnificent land and heroic people'

GT: Beyond the Nanjing Massacre-themed works, what other historical subjects have you tackled?

Wu: My connection to anti-war sculptures dates back to 1985, the 40th anniversary of the Victory in the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression. That year, invited by my hometown of Dongtai, Jiangsu Province, I created the large-scale sculpture titled New Fourth Army Marching East, which remains a key city landmark in Dongtai. Later, I created Marching East and Memorial Group Sculptures for the Reestablishment of the New Fourth Army Headquarters for the New Fourth Army (a main anti-Japanese armed force led by the Communist Party of China) Memorial, depicting soldiers charging through the flames of war. I've also created works on other resistance themes, such as sculptures of the Eighth Route Army (a main anti-Japanese armed force led by the Communist Party of China), General Zuo Quan (a member of the Communist Party of China and a well-known Chinese hero of the War against Japanese Aggression), and the Long March. Additionally, I've crafted statues of international friends from the war, like John Rabe, whose statues stand in both Nanjing and Berlin.

My historical and cultural sculptures, such as those of Confucius and Laozi, have been erected in Greece and Italy. Statues of Karl Marx and Deng Xiaoping tell the world stories of China's revolution and history. Notably, in Japan, I had placed the statue of Monk Jianzhen in Ueno Park and Monk Yinyuan's statue in a 400-year-old temple in Nagasaki, along with Sun Yat-sen's statue in Fukuoka. By bringing these great Chinese figures to Japan, I ensure the local Japanese remember China's historical contributions as the sculptures spread China's culture.

Today, we present to the world a great China: a land of etiquette, a nation always embracing peace and benevolence. Under the vision of building a community with a shared future for mankind, we must tell the world about a credible, respectable, and lovable China.

GT: You mentioned that sculpture is a dialogue across time. Your works span generations. What kind of peace and historical perspective do you want to pass on to the next generation?

Wu: What is the meaning of sculpture? All artistic creation must stem from values. Contemporary Chinese art should contribute to building a community with a shared future for mankind, serve the public, and elevate aesthetic literacy. I've repeatedly advocated for strengthening art education, especially in primary and secondary schools. Thus, the subjects and figures I create are all those with heroic deeds in Chinese history, worthy of becoming eternal role models through sculpture. For example, my statue of Yuan Longping, the father of hybrid rice, stands at the Italian Academy of Sciences, one of the oldest academies in the West. Yet the academy showcases a contemporary Chinese scientist, which is no small feat. In the past, in our schools and academies, people often spoke of Albert Einstein, Isaac Newton, and others - rightfully so. This proves that our era is nurturing great scientists, thinkers, and artists. Therefore, artists have found the best subjects and the finest environment to create. We should use our works to sculpt our magnificent land and heroic people, telling China's story through art.