ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

How Chinese romance takes flight in space mission names

Ancient tales reborn in orbit

Editor's Note:

In contemporary China, an increasing number of names draw inspiration from Chinese history and classical texts. From high-tech products to newborns, names offer a window into the nation's rich cultural heritage and ongoing development.

To unpack the allure behind these names, the Global Times launches the Chinese Calling Card trilogy. The first installment will delve into the cosmic romance of China's aerospace programs.

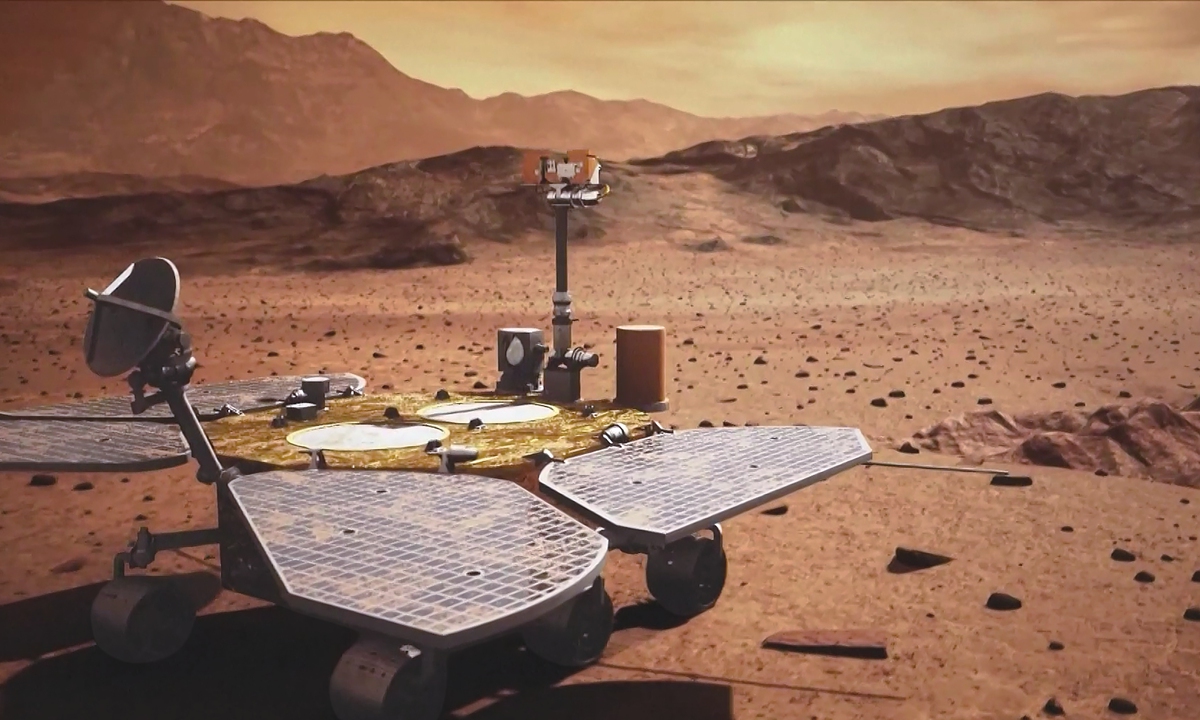

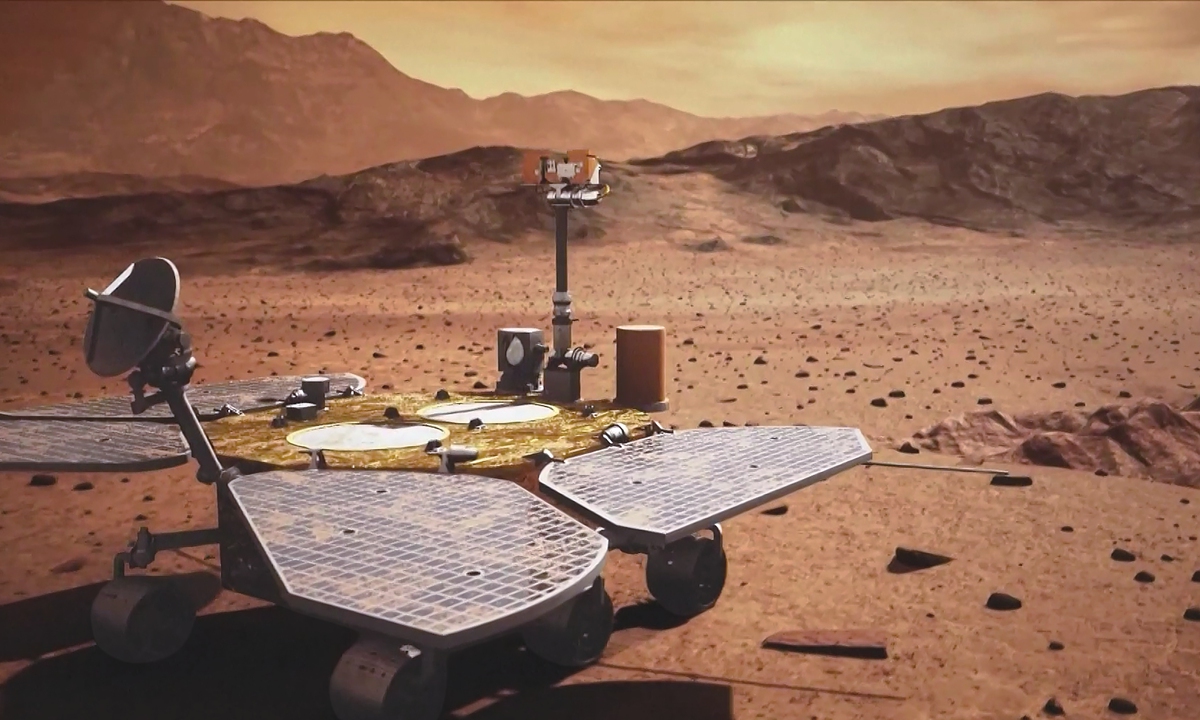

On the dusty plains of Mars, a rover named after an ancient fire god, Zhurong, is rewriting planetary history. This January, by studying the detection data collected by the rover, Chinese geologists have found that the Martian surface had still exhibited significant aqueous activity approximately 750 million years ago, proving that water existed on the red planet several hundred million years earlier than previously thought.

For many, what makes this scientific breakthrough even more evocative is how Zhurong, named for the Chinese deity who brought humanity the gift of flame, now scours a world that, in Chinese, is called Huoxing, or Fire Star.

Some Chinese netizens commented on social media that sending a rover named after the god of fire to the fiery planet is a kind of "Chinese romance."

The name Zhurong was chosen for its symbolic weight: "It embodies igniting the spark of interplanetary exploration and guiding humanity's unceasing quest to surpass itself," according to China National Space Administration (CNSA).

Zhurong is not an isolated case. Over the past decades, China has built a coherent and culturally rich naming system for its space endeavors. These names stem from a rigorous, systematic and deeply meaningful naming mechanism, most of which follow a process similar to that used for the Mars rover, while others are designated directly by the project's leadership through discussion.

From the Chang'e (China's moon goddess) rover exploring the lunar surface to Zhurong roaming Mars, from the Tiangong (lit. heavenly palace) Space Station orbiting Earth to the Xihe (China's sun goddess) satellite chasing the sun, these Eastern names have woven a cosmic narrative where mythology meets modern science, turning "Chinese names" into cross-border cultural symbols.

Hu Yu, dean of Tsinghua University's Institute for Culture Creativity, told the Global Times that these names construct a symbolic system bridging ancient myths and modern technology.

"In traditional Chinese cosmology, the heavens were an ordered realm of deities. By 'inviting' these mythological figures into space with new scientific missions, China expresses its cultural confidence," he said.

Myth, poetry and philosophy

The foundation of this naming system was laid in the early 2000s. When China launched its lunar exploration program in 2004, it was officially named the Chang'e Project.

Zheng Changling, a research fellow at the Chinese National Academy of Arts, told the Global Times that this practice reflects the continuity of Chinese civilization.

"China's ritual civilization is deeply rooted in our collective experience, shaping the worldview of generations," he said, adding that this is a natural extension of cultural traditions in a modern scientific context.

"Our cross-border surveys show that international audiences with basic knowledge of Chinese culture can fully grasp the civilizational implications," Zheng said.

In 1993, when CNSA solicited names for its manned spacecraft, Shenzhou (lit. divine craft) emerged victorious from thousands of proposals.

From Shenzhou-1's maiden flight in 1999 to Shenzhou-23's orbital mission in 2026, these names have witnessed China's space journey from infancy to maturity.

The new generation of crewed spacecraft, Mengzhou (lit. dream boat), echoes to the line by Li Bai from Tang Dynasty (618-907), "Set sail for the sun like the sage in a dream," while the upcoming Lanyue (lit. seize the moon) lunar lander will turn the poetic longing "to pluck stars with one's hands" into reality when China lands astronauts on the moon by 2030.

Zhu Xinhua, an associate professor at the School of History, Capital Normal University, told the Global Times that China's space program has established a symbolic system that integrates Eastern culture and philosophical thinking.

This system draws from diverse and profound roots within China's traditional heritage, including ancient mythological lore, classical poetic imagery and early religious thought.

"At its core, it reflects a traditional Chinese understanding of the cosmos and the relationship between humanity and the universe," Zhu said.

Popularizing science

In comparing Chinese and Western naming logic, Zhu pointed out that Western missions frequently honor individual scientists or constellations. This practice stems from an individualistic tradition and the empirical scientific culture that followed the Industrial Revolution.

China's names emphasize historical continuity and collective cultural memory, presenting a distinct aesthetic and spiritual dimension.

Eastern and Western naming philosophies share common ground, Zhu said. For instance, the US Apollo moon-landing program drew its name from the Greek god of the sun.

However, China's space naming may be more expansive and systematic. The lunar exploration program, for example, is named Chang'e - the moon goddess, while the lunar rover is called Yutu (Jade Rabbit) and the relay satellite Queqiao (lit. magpie bridge), together forming a more cohesive narrative framework.

At one Beijing's Xinhua Bookstore near the Second Academy of China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation, manager Dong Hang told the Global Times that space-themed books and cultural products are particularly popular among young readers.

"The Shenzhou series, buoyed by its strong brand recognition, remains a steady best-seller in both books and model kits," she told the Global Times.

As China enters a "high-density mission year" in 2026 with four missions, including Tianzhou-10, Shenzhou-22 and Mengzhou-1 planned, the nation's space program continues to carry its cultural heritage into the cosmos.

"China's space naming system is a model of creative transformation of traditional culture. It infuses major scientific projects with humanistic warmth and provides an inspiring path for telling Chinese stories globally," Hu summarized.

In contemporary China, an increasing number of names draw inspiration from Chinese history and classical texts. From high-tech products to newborns, names offer a window into the nation's rich cultural heritage and ongoing development.

To unpack the allure behind these names, the Global Times launches the Chinese Calling Card trilogy. The first installment will delve into the cosmic romance of China's aerospace programs.

China's first Mars rover Zhurong Photo: VCG

On the dusty plains of Mars, a rover named after an ancient fire god, Zhurong, is rewriting planetary history. This January, by studying the detection data collected by the rover, Chinese geologists have found that the Martian surface had still exhibited significant aqueous activity approximately 750 million years ago, proving that water existed on the red planet several hundred million years earlier than previously thought.

For many, what makes this scientific breakthrough even more evocative is how Zhurong, named for the Chinese deity who brought humanity the gift of flame, now scours a world that, in Chinese, is called Huoxing, or Fire Star.

Some Chinese netizens commented on social media that sending a rover named after the god of fire to the fiery planet is a kind of "Chinese romance."

The name Zhurong was chosen for its symbolic weight: "It embodies igniting the spark of interplanetary exploration and guiding humanity's unceasing quest to surpass itself," according to China National Space Administration (CNSA).

Zhurong is not an isolated case. Over the past decades, China has built a coherent and culturally rich naming system for its space endeavors. These names stem from a rigorous, systematic and deeply meaningful naming mechanism, most of which follow a process similar to that used for the Mars rover, while others are designated directly by the project's leadership through discussion.

From the Chang'e (China's moon goddess) rover exploring the lunar surface to Zhurong roaming Mars, from the Tiangong (lit. heavenly palace) Space Station orbiting Earth to the Xihe (China's sun goddess) satellite chasing the sun, these Eastern names have woven a cosmic narrative where mythology meets modern science, turning "Chinese names" into cross-border cultural symbols.

Hu Yu, dean of Tsinghua University's Institute for Culture Creativity, told the Global Times that these names construct a symbolic system bridging ancient myths and modern technology.

"In traditional Chinese cosmology, the heavens were an ordered realm of deities. By 'inviting' these mythological figures into space with new scientific missions, China expresses its cultural confidence," he said.

Myth, poetry and philosophy

The foundation of this naming system was laid in the early 2000s. When China launched its lunar exploration program in 2004, it was officially named the Chang'e Project.

Zheng Changling, a research fellow at the Chinese National Academy of Arts, told the Global Times that this practice reflects the continuity of Chinese civilization.

"China's ritual civilization is deeply rooted in our collective experience, shaping the worldview of generations," he said, adding that this is a natural extension of cultural traditions in a modern scientific context.

"Our cross-border surveys show that international audiences with basic knowledge of Chinese culture can fully grasp the civilizational implications," Zheng said.

In 1993, when CNSA solicited names for its manned spacecraft, Shenzhou (lit. divine craft) emerged victorious from thousands of proposals.

From Shenzhou-1's maiden flight in 1999 to Shenzhou-23's orbital mission in 2026, these names have witnessed China's space journey from infancy to maturity.

The new generation of crewed spacecraft, Mengzhou (lit. dream boat), echoes to the line by Li Bai from Tang Dynasty (618-907), "Set sail for the sun like the sage in a dream," while the upcoming Lanyue (lit. seize the moon) lunar lander will turn the poetic longing "to pluck stars with one's hands" into reality when China lands astronauts on the moon by 2030.

Zhu Xinhua, an associate professor at the School of History, Capital Normal University, told the Global Times that China's space program has established a symbolic system that integrates Eastern culture and philosophical thinking.

This system draws from diverse and profound roots within China's traditional heritage, including ancient mythological lore, classical poetic imagery and early religious thought.

"At its core, it reflects a traditional Chinese understanding of the cosmos and the relationship between humanity and the universe," Zhu said.

Popularizing science

In comparing Chinese and Western naming logic, Zhu pointed out that Western missions frequently honor individual scientists or constellations. This practice stems from an individualistic tradition and the empirical scientific culture that followed the Industrial Revolution.

China's names emphasize historical continuity and collective cultural memory, presenting a distinct aesthetic and spiritual dimension.

Eastern and Western naming philosophies share common ground, Zhu said. For instance, the US Apollo moon-landing program drew its name from the Greek god of the sun.

However, China's space naming may be more expansive and systematic. The lunar exploration program, for example, is named Chang'e - the moon goddess, while the lunar rover is called Yutu (Jade Rabbit) and the relay satellite Queqiao (lit. magpie bridge), together forming a more cohesive narrative framework.

At one Beijing's Xinhua Bookstore near the Second Academy of China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation, manager Dong Hang told the Global Times that space-themed books and cultural products are particularly popular among young readers.

"The Shenzhou series, buoyed by its strong brand recognition, remains a steady best-seller in both books and model kits," she told the Global Times.

As China enters a "high-density mission year" in 2026 with four missions, including Tianzhou-10, Shenzhou-22 and Mengzhou-1 planned, the nation's space program continues to carry its cultural heritage into the cosmos.

"China's space naming system is a model of creative transformation of traditional culture. It infuses major scientific projects with humanistic warmth and provides an inspiring path for telling Chinese stories globally," Hu summarized.