ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

Relaxed charm of Shichahai Grandpa’s hand-carved woodworks

'Ugly in just the right way'

Hu Maoying's wood carvings Photos: Jiang Li/GT

In the afternoon, a narrow alley near Shichahai, a scenic spot in Beijing has already drawn a crowd of people. At the center sits 65-year-old Hu Maoying, head lowered, steadying a block of wood with his left hand while guiding a carving knife with his right. Fine wood shavings fall softly with each stroke.Freshly finished, larger carvings are snapped up almost as soon as they are placed on display. "I've been lining up for days," someone blurts out. The crowd includes visitors who have traveled from other provinces, as well as young people in Beijing who have shown up at the same time for several afternoons in a row, hoping to "get lucky."

The stallholder - dubbed the "Grandpa Woodcarver" by netizens, rose to online fame after several on-site videos were widely shared on social media platforms. In the clips, he carves quietly and unhurriedly, while the figures on his table appear rough-hewn and abstract, standing in stark contrast to the polished, delicate handicrafts more commonly seen.

Some online users say the carvings "look like something, yet not quite." It is precisely this hard-to-define quality that has fueled lively discussion and copycats. Drawn by the buzz, some visitors have traveled long distances simply to buy a carving that is, as one fan put it, "ugly in just the right way."

Hu Maoying's wood carving of a pig

Breaking conventionsHu, who hails from East China's Anhui Province, has been running his stall at Shichahai for more than a decade. His wood carvings, mostly small animals, are priced between 20 and 50 yuan ($2.80-$7.20). No two pieces are the same, and he makes no deliberate attempt to pursue conventional notions of beauty.

His most popular piece, known online as "LinaBell" is, in Hu's own words, simply a "three-nothings," neither quite this nor that. Netizens have jokingly dubbed it an "alien LinaBell" or "so eerie it could find its own way home if lost."

Paradoxically, it is precisely this "ugly-cute" quality and sense of liveliness that has drawn such a large number of buyers.

"At first, I just saw a child carrying a toy on her bag and thought it looked cute, so I carved one," Hu told the Global Times. "I never expected it to become a bestseller."

"I just carve however I feel. If I think it's fine, then it's fine. I don't really care what others think about it," he said. Hu does not go out of his way to explain what his carvings are meant to resemble, nor does he pursue any so-called sense of completion.

When someone asks, "What's this?" he glances up briefly and replies, "This one is a sheep… that's a rabbit," before lowering his head and continuing to carve.

Before his sudden rise to popularity, Hu's stall went largely unnoticed. In earlier years, he worked as a cleaner in Beijing and took extra shifts at a supermarket after work. "It was too exhausting," he recalled, which prompted him to gradually turn to woodcarving.

Business was slow at first, with only a few pieces sold each day. Today, however, crowds gather constantly around his stall, turning it into a distinctive sight in the area.

What truly draws young visitors, perhaps, is not just the "ugly-cute" carvings themselves.

Wang Lixin, a visitor from North China's Hebei Province, told the Global Times that he and his girlfriend traveled to Shichahai after seeing posts about Hu on the social media platform Xiaohongshu, or RedNote app. They lingered at his stall for a long time.

"We weren't even focused on choosing something to buy - we just wanted to watch a bit longer," Wang said. In their view, watching Hu carve wood is an experience in and of itself. "He works slowly, without any rush, as if nothing else in the world bothers him. When you stand beside him, your own pace seems to slow down too."

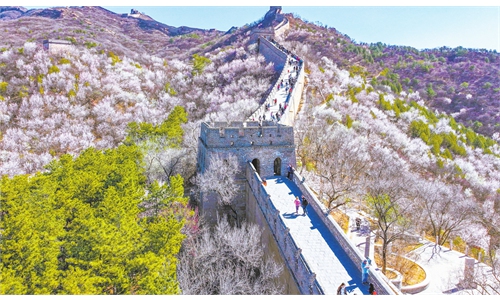

People watch Hu Maoying, known as Shichahai Grandpa, carve wood figurines in Beijing on January 14, 2026. Photo: VCG

Sense of relaxationThis unhurried, unpressured demeanor has been repeatedly noted by young visitors. Some say, "He isn't anxious at all," while others remark, "He's confident in his work and doesn't need anyone else's approval."

Li Tuo, a Beijing-based scholar specializing in psychology and cultural studies, told the Global Times that Hu's rise to fame is no coincidence. "These carvings do not attempt to conform to mainstream aesthetic standards; on the contrary, they explicitly reject the notions of 'must resemble something' and 'must be refined,'" Li explained. "What truly moves young people is his life attitude behind the work - one not driven by efficiency or results."

In Li's view, the carvings' abstraction and imperfection leave room for interpretation. "You need to judge and imagine for yourself; you can even add a sense of humor. This interaction transforms consumption from a mere transaction into emotional engagement." In this process, young visitors project their own stress, anxiety, and expectations onto these tiny carvings.

"They aren't souvenirs; they're more like reminders," Li said. "Reminders that life doesn't always require a standard answer at every step."

As night falls and the crowd thins, Hu packs up his tools and prepares to go home. When asked if he would return the next day, he simply replied, "As long as it doesn't rain, I'll be here."

On a winter day at Shichahai, these so-called "Beijing's new ugly-cute souvenirs" and the calm figure of an elderly man together form a unique urban scene.

Unassuming yet constantly taken home; imperfect yet repeatedly cherished - perhaps it is precisely in this state of "no need to prove anything" that young people rediscover a long-lost sense of ease.