Migrants among us

Migrants make up more than a third of Beijing's population, according to a report released by Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics on February 7. This migrant group includes the expected construction and labor force as well as college students, white collar business people from other provinces and expats. It may well include you.

As the World Survey Day of Living Conditions falls on the last day of February, Metro Beijing conducted its own research to get a better look at the living conditions of five different groups of migrant Beijing dwellers, which varied widely.

"It is an objective fact that there are big gaps among living conditions of those different groups in Beijing, since they vary in income and class," said Dong Liming, a professor at the College of Urban and Environmental Sciences of Peking University, specializing in real estate development and urban planning.

Dong said the disparity could be improved through increased investment in construction, and new policies about population, housing purchases and residential zoning to help the city expand strategically, not blindly.

"The most important thing is for migrant people to be considered not as migrants, but as members of the urban community in Beijing," said Dong.

Let's meet a sample of Beijing's migrants.

Migrant workers

Liu Guangsheng, 30, truck driver, Christian, originally from Nanyang, Henan Province, Beijing resident for five years

Living in a single room less than 10 square meters in Picun village, Chaoyang district, with his wife and two sons, ages 8 and 5

Rent: 100 yuan ($16.04)

Liu's room is small, dark, wet and cold. There is one bed, one stove and one desk. There is a small window, but it's blocked by the dog shed right in front of it, and doesn't let in much sunlight.

The makeshift house, built about 10 years ago, has a thin door and walls, which shake from the wind. Liu has a dog called Little Black to guard his truck, which is parked right outside of the house.

Since there is not much space for cooking, eating or anything else, they use a public toilet at the end of the street, and eat and hang out at his sister's house. Liu's sister, brother-in-law and two nieces live in a 15-square-meter room next-door.

The room is small for a big family like Liu's. When Metro Beijing entered the home, the kids were having breakfast on an old folding table, which was put away later to make room for guests.

The housewives are neat with the housework, though conditions out of their control leave the room dull and dirty.

"The stove is necessary for cooking and warming up the house, but some smoke can't get out efficiently," explained Liu. "The rain and the wind come in through the roof," Liu's sister complained.

Liu noted that the village is isolated from urban life – far from major hospitals, subway stops and public schools.

"It's the best we can afford at the moment," said Liu.

Petitioners

Tang Jianchun, 51, originally a peasant from Xiangfan, Hubei Province, Beijing resident for 12 years

Living under a bridge

Rent: None

Under the grand Yongdingmen Bridge, which is fairly close to the State Bureau for Letters and Calls, dozens of Beijing's petitioners seek shelter. They crouch on ragged, secondhand quilts or mattresses. Their skin is tanned and cracked from years of sun and wind exposure.

When Metro Beijing approached the group, many rushed up to share their cases and how they suffered injustices. With a strong regional accent, Tang told Metro Beijing that he is petitioning because he was wronged by the court system, framed and punished twice for committing arson once.

The bridge barely functions as a roof, since snow and rain can pour down right through the cracks. This winter is particularly cold, so Tang puts on everything he has.

"We just get up and start running during the night, and come back to sleep once we feel warm," laughed Tang.

Tang has only one old quilt, and the rest are picked out from trash dumps, or are charitable gifts. Most of the petitioners make a living by picking up trash. Everyday, Tang picks up water from public toilets or hospitals nearby and boils it in a shabby, black pot, and then shares it with his neighbors or cooks with it.

Whenever the government launches a new strategy for removing petitioners, Tang says his group just moves and comes back a few days later. Before Tang moved to this spot in November 2011, he had lived under many bridges and in many underground passages over the last 12 years.

With a thin hope of getting his case re-examined, Tang plans to live on like this.

"I don't care about living conditions," said Tang.

New college graduates

Yu Junjie, 25, reporter, originally from Jiangsu Province, graduated from China Foreign Affairs University, Beijing resident for four years

Living in an apartment on the third floor of a five-story building built in the 1980s, near Caihuying Bridge, Fengtai district

Rent: 3,000 yuan

Walking up the gloomy, narrow staircase, one can only expect the inside of the apartment to be dark, too. Yu's room faces the south, but the balcony has air leakage, so it is temporarily sealed by cloth, blocking the sunshine out. The lights in the living room need to be on even at noon.

Yu's room has all the necessary furnishings: a big wardrobe, a computer desk, two folding chairs, a bed and curtains that used to be sheets. It's comfortable, but together they give the impression that Yu doesn't intend to live here for a long time. It's a temporary shelter of sorts.

"It is quiet and clean, but too far away from work, which is about 5 kilometers away, and without any subway facilities or direct bus lines," said Yu.

Public services nearby are also lacking.

"There is only one small shop across the street, which is very inconvenient since you have to cross a wide road for it," said Yu.

But Yu still likes this current apartment better, because his last apartment had terrible air quality problems due to cheap indoor decorations, which caused his lymph nodes to swell.

Yu doesn't know any of his neighbors.

"It's just a room to live in, a place to shelter myself. I'm afraid it's hard to find a sense of belonging in a rental apartment," Yu said.

For many newly graduated young people like Yu, they realize their small college dorms were precious in this highly-priced city.

Expats

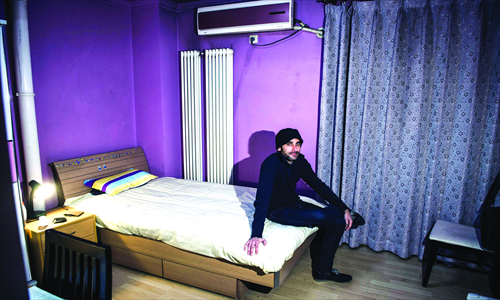

Jose Guerrero, 30, architect, originally from Spain, Beijing resident for three months

Living in one bedroom of a 100-square-meter compound apartment in the Xinjiefang neighborhood of Chaoyang district

Rent: 1,660 yuan

Guerrero moved into his first apartment only two months ago, and he already likes it a lot.

The apartment has modern design and facilities. The room was painted violet by the previous dweller, which Guerrero is still trying to get used to. It's close to work, and only 15 minutes away from the subway. It's nearby a variety of shops, both expensive and cheap ones.

One of the problems, Guerrero says, is that the washing machine doesn't work well. He also can hear the noises of the elevator going up and down from his room. But the real problem for Guerrero is that there are no bars in the neighborhood – he has to go all the way to Houhai.

Guerrero told Metro Beijing he's probably the only foreigner in the neighborhood, but it's not a problem for him. He shares the compound with one Chinese girl and a couple, who have helped him a lot. They can communicate, with the help of the translators on their smart-phones.

Although it's not as good as his house back in Spain, Guerrero feels very lucky that as a foreigner with little knowledge about Beijing or the language, he was able to find an apartment with the help of a co-worker.

"Before this one I saw five or six apartments. They were terrible," said Guerrero, noting that he's very satisfied now.

White collars

Sophie Chen, 33, a purchasing clerk in the mechanical industry, originally from Sichuan Province, Beijing resident for 9 years

Living in a three-bedroom apartment with her two female roommates, on the 14th floor of a building built in the 1990s, near Chaoyang Park

Rent: 2,200 yuan

Chen recalls the first year she came to Beijing when she lived in a "patchwork apartment," sharing with a dozen other people. The cost was 200 yuan each month for one bed.

"As my salary goes up, I change apartments," Chen said.

Her latest upgrade has a large bedroom, solid wood floor, sofa and a big television in the living room. Transportation is convenient. It's near Sanlitun and Chaoyang Park, which Chen considers important since her parents will like visiting the park if they come to visit.

The neighborhood and property managers are nice, too.

"I'm very happy with it. I always head back as soon as I'm off work, and sit in the sofa comfortably for some time," said Chen.