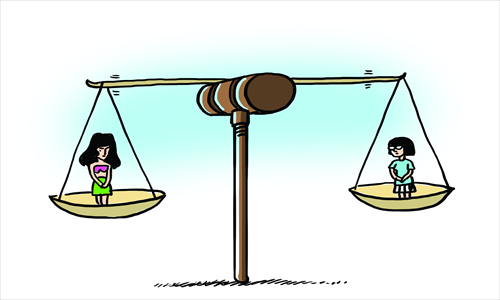

‘Good girls’ or bar girls, the law must give justice to all rape victims

Tsinghua law professor Yi Yanyou dropped himself into a world of outrage and criticism earlier this week, after commenting on the controversial Li Tianyi gang-rape case.

Yi first wrote on his Weibo that prostitutes, escorts and bar girls were more likely to consent to sex, and thus it was more acceptable to rape one of them than rape a normal girl.

Under a barrage of online criticism, Yi budged ever so slightly, deleting his post and clarifying by saying that it's not OK to rape a bar girl, but that raping a bar girl would do less harm than raping a "good girl."

After other minor alterations, Yi was challenged at a press conference, where he accused his online critics of being a "mob" and implied that online comments could easily be silenced.

He later apologized, but by then the damage was done.

For all of Yi's protestations that he still said rape was bad, as one who teaches law at an elite institution, he must understand that - intended or otherwise - the implicit meaning and most obvious interpretation of his comments is that some people are less deserving of legal protection than others.

Setting aside how outrageously insulting his comments were, let's consider for a moment the attitude behind them and what this attitude means when formulating laws.

Yi is the director of the Centre for Evidence Law at Tsinghua University. His voice is an influential one, and yet, he doesn't seem to understand that the core basis for having laws in society is to ensure equality for all.

This is pretty basic, fundamental stuff. It's why punishments for crimes, at least on paper, are always based upon the severity of the crime, rather than the profession of the offender or the victim.

For laws to function consistently in application is particularly crucial for a country like China, which struggles with the improvement of its legal system in the face of widespread graft and enforcement difficulties.

Given Yi's position, he must understand that morals are incredibly subjective, and the goal of laws is to find some kind of common ground within each society - this is why laws are different in every country.

But once we start saying that it's OK to commit crimes against some people because they are perceived to have lower moral standing, then I, for example, might judge Yi to be less worthy of legal protection than other people, as crimes against him would do less harm than crimes against people who have more respect for women who work in bars.

It doesn't take much imagination to see the problems this would cause for society. We cannot simply call open season on people we don't like, however much we might want to.

Regardless of the "harm" Yi was talking about, his comments have done their own harm.

Yi must have taught many bright, up-and-coming young women who dream of a career in law. But their perception of the law, based on Yi's teachings, would judge them less worthy of protection in the eyes of the law if for whatever reason they found themselves working as a prostitute or in a bar.

Perhaps the most tragic truth of this controversy is the way it has reminded us of the fact that all over the world, there are people at all levels of society who feel that rape isn't serious when the woman isn't seen as somehow "virtuous" or is "asking for it."

It's unlikely we'll be able to resolve that issue any time soon, but hopefully we can ensure that when specific things like laws are considered, we can demand that the people writing them understand that often a black-and-white attitude is necessary when translating subjective morals into concrete laws - in this case, rape is rape, regardless of who the victim is.

The author is an editor with the Global Times. daviddawson@globaltimes.com.cn