Central Asia unlikely to become another unstable Middle East

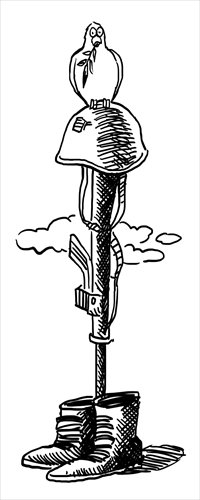

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

Whither Central Asia after the US withdrawal from Afghanistan? That is the question on the lips of Central Asia watchers globally, as well as policymakers and pundits in the region. There are numerous theories, but few take into account the full picture of shifting geopolitical tectonics.

The narrative popular in some circles in Washington and propagated by some in Kabul and elsewhere in the region is that the greatest upcoming threat will be the potential "spillover" of extremist Islamism into the post-Soviet space.

The coming great power vacuum in the region, when the US loses interest and Russia finds itself less capable of asserting itself, is often linked to the supposed spillover effect to create a swirl of potential political instability, perhaps resembling the current tumult across the Middle East.

Leaders in Central Asia are said to be terrified of the potential for not just a Kyrgyzstan-style perpetual color revolution, but a military coup such as in Egypt or even the sort of prolonged civil war we are witnessing in Syria.

These are not illegitimate concerns for some of the leaders of Central Asia. Afghanistan itself certainly faces a very uncertain future. And there are parts of the wider region in which separatism and violent extremism are genuine potentialities.

But the question of whether Central Asia will emulate the Middle East after the US withdrawal from Afghanistan is a wrong one. Concerns about unrest in the region are generally not directly linked to Afghanistan's political and security future.

Social conditions in every post-Soviet Central Asian state, including Kyrgyzstan, are not all that similar to the Arab world or Iran. Religious realities are not nearly as conducive to the so-called radicalization of populations. The motivations for unrest are specific to the region: its geography, identities and varied socioeconomic environments.

The best question to ask about the region does have to do with a great power vacuum, not because this might be filled by extremism and political unrest, but because the geopolitics of the region is fundamentally changing as the US withdrawal approaches.

Some of this is related to Washington's priorities, but much of it is independent of that variable. The central question hanging over the region at the moment and going forward for the next decade will be: What role does China play as the most consequential outside actor in Central Asia?

The US is actively involved in a downplaying of priorities and curtailing of relationships in the region. Policymakers in Moscow, for all of their bombast, have shifted to a strategy of consolidation of interests and power.

Going forward, Russia will almost certainly focus on maintaining overbearing security relationships with the smaller states of Central Asia: Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

Russia's security influence in the rest of the region is token at best, while its economic leverage is in retreat in every one of its former Central Asian colonies. Plans for a Eurasian Union are a feeble rear guard action aimed less at NATO and the West and more at the increasing relevance of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).

The SCO has China as its sponsor. And, while it is not clear at all that China has designs for control of any kind over Central Asia, it is the power with the most momentum in the region. It has now become cliché to say that Central Asia's markets are flooded with Chinese goods and businessmen.

CNPC has supplanted Gazprom as the decisive energy player from Karamay to the Caspian, and it is now rubbing shoulders with Western energy companies offshore. CNPC and other Chinese companies are some of the only major investors in Afghanistan. Whether Beijing intends it or not, Central Asia is China's for the taking.

The next question, therefore, that Chinese policymakers should be asking themselves about Central Asia, is about the political consequences, or perhaps responsibilities, of this presence.

The SCO summit later this year will focus again on Afghanistan's future, but this is too little and too late. And at the moment, the SCO does not have the institutional tools to shape the security landscape of the region, whether the countries of Central Asia want it to or not.

Central Asia may not harbor the same kind of short-term threats as the Middle East, but it has its own sui- generis concerns and opportunities. Whether the region presents one or the other will depend much on China's understanding of the role that has been thrust upon it.

The author is co-editor of chinaincentralasia.com. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn