Tokyo’s nerves on Beijing-Seoul ties needless

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

Since taking power in late 2012, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe pledged to reinvigorate his nation's long-sought but somewhat stagnated aspiration to become a "normal state."

He soon announced plans to rejuvenate Japan's economy through Abenomics, to expand the limits of its military boundaries, and to complete the return of the remaining Japanese abductees from North Korea.

To realize the last plan, Abe has expressed his willingness to talk and meet his North Korean counterpart. Notwithstanding our shared sympathy about Japan's anxiety for its abducted nationals, we still wonder about Abe's true motives.

One obvious motif is to successfully garner the popular support the solution of abduction case will bring to his cause.

The Abe government believes in the connectivity of the abduction case with Japan becoming a normal state. Strong public backing from the endorsement on the leadership it gets from the populace will allow Abe to lead his nation to a long-sought goal of becoming a militarily normal state.

The Abe government also desires to drive a wedge on the relationship between China and South Korea.

Japan is not the only country sensitive to the close collaboration and cooperation between the two on various agendas. They range from historical issues and territorial conflicts with Japan to summit politics to North Korean nuclear problems.

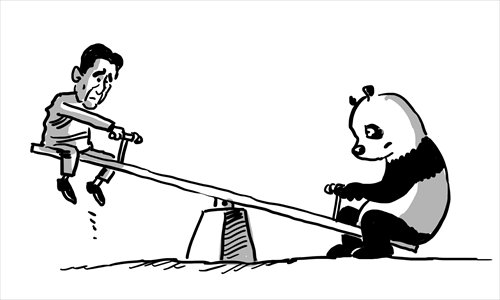

On all these cases, a compelling feeling in Japan is that it is being shunned. China and South Korea are perceived to be getting so close that the weight in the regional order will tilt to heavily favor them.

What has prompted this worry? There is little concrete evidence of the shift, but much speculative interpretation on their recent diplomatic collaboration and seemingly high amicability present in the mutual feelings between the two heads of state.

China has adopted its own punitive sanctions on North Korea on three different occasions since the inauguration of the new leadership. With a newly elected president in late 2012, South Korea has also shown a tougher attitude to the North's erratic behavior over issues such as the closing down of Kaesong industrial complex, live-firings near inter-Korean border, "satellite" launch and nuclear test.

Another argument claims that China and South Korea's prolific diplomatic achievements have increased Tokyo's feeling of isolation.

Apart from North Korea policy, Beijing and Seoul early this year unveiled some historical monuments as part of resurrecting their past history against Japan.

To Tokyo, these monuments are a mere reminder of their tragic losses and unfortunate incidents. To Beijing and Seoul, they commemorate the lost lives of their ancestors' struggle against Japanese imperialism.

How is it that Japan attaches such diplomatic meaning to their collaboration? There's no need to put such heavy weight on it, especially since the amicability is not new. The start of the collaboration can be traced as far back as to the late years of then South Korean president Kim Dae-jung's government in the early 21st century.

If Japan were to really worry about South Korea getting too close to China, it should have been under former president Lee Myung-bak's government. Lee met his Chinese counterpart many times while in office. Lee's frequent meetings with China's top leader were never a cause of concern to Japan.

Before Japan gets concerned about regional isolation, it must find ways to improve relations with those whom it has a "normal" relationship. It will be much more cost-effective to overcome its concerns of being isolated.

By choosing to be the black sheep in the crowd, Abe will not succeed in accruing the support he seeks from not only his own populace but also regional colleagues.

A peaceful and much more meaningful key to retrieving public endorsement on his leadership would be to successfully overcome the mounting challenges that Abenomics will eventually have to confront, and fundamental reforms of the nation's economic structure.

The author is professor at Kyung Hee University and visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn