HOME >> OP-ED

Trust requires understanding on both sides

By Rong Xiaoqing Source:Global Times Published: 2014-10-9 23:03:03

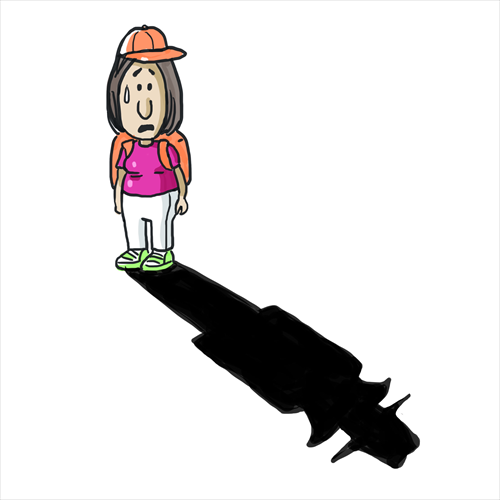

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

Before my visit to China last month, an overdue trip to a home country I had not visited in six years, I prepared myself for all the things that could possibly go wrong. But there was one thing I didn't have on my list. It caught me off guard for the first time right when I arrived in Beijing after a 14-hour flight from New York, at the front desk of the Jianguo Garden Hotel.

"Ma'am," a very polite baby-faced receptionist frowned while she was flipping through my passport, "where is your visa page?"

This sounds like a reasonable question, except that my passport was issued by the Chinese consulate in New York. About 10 minutes and a few supervisors later, I finally convinced them that a Chinese citizen doesn't need a visa to come back to her own country.

Problem solved, I checked myself in without knowing that was only the beginning. In the next 19 days, I traveled to seven more cities and checked into a dozen or so hotels as an independent budget tourist who had wisely taken advantage of a few free and discounted nights here and there by using accumulated reward points.

Some of these were five star international hotels, and some were guest houses run by local residents. All but the two in Shanghai questioned me for using my Chinese passport as an official ID.

Some demanded that I present my American green card. One even initially asked me to go to the local police precinct in person to get approval to stay in the hotel. Many of them kindly told me to get a foreign passport or use a Chinese ID card to avoid trouble next time.

I understand the strict ID checking at hotels was partly for anti-terrorism purposes, especially in the capital city. But what perplexes me is why a passport, which is issued by the Chinese government using an application process that is as rigid as for a resident's ID, if not more, is not considered a legitimate form of ID within China.

Many overseas Chinese, myself included, would like to maintain our Chinese citizenship, but our Chinese resident's ID may have long expired. The Chinese passport is the only ID that proves our Chinese identity.

The skepticism about the credibility of this document in China only leads to a heartbreaking conclusion - that living abroad, we are no longer trusted by the system in our home country.

But an assertion based on frustration and an element of rage is at best partial and incomplete. This one is no exception.

When I thought through the trust issue, another layer emerged. If the system in my country doesn't trust me any more, do I still trust the system in my country? I found I cannot give a certain answer when I asked myself this question.

When I was in China, I did worry about food poisoning, though it didn't happen. I worried the taxi drivers would cheat me when they figure out I am not a local. This didn't happen either, or not that I noticed. I was prepared to get sick because of the polluted air. The air was quite polluted in most cities I visited, but I didn't get sick.

A Tibetan woman at Jiuzhaigou, a famous scenic spot in Sichuan Province, opened her house and introduced Tibetan culture to tourists for free. I thought she was planted there by the propaganda department.

It turned out at the end she was probably more interested in selling the tourists souvenirs, some of which were quite costly. Not such a surprise in any country frankly.

I could blame the Western media's coverage of China for my paranoia. But I know the real reason is that I have not visited China for so long. So what may sound like personal paranoia contains a broad lesson for all human relationships, person-to-person and country-to-country: Distance inevitably creates misunderstanding and mistrust. But we often like to point fingers at others for sour feelings and forget that trust is a two-way road.

The only way to break the vicious cycle of mistrust is for people in a relationship to see and communicate with each other face to face, as often and as openly as possible.

This might be a message the two most powerful countries in the world should send to each other during US President Barack Obama's upcoming trip to China and his meeting with his Chinese counterpart.

The author is a New York-based journalist. rong_xiaoqing@hotmail.com

Posted in: Columnists, Viewpoint