HOME >> OP-ED

THAAD isn’t answer to Seoul’s anxiety

By Chung-in Moon Source:Global Times Published: 2015-5-28 22:28:02

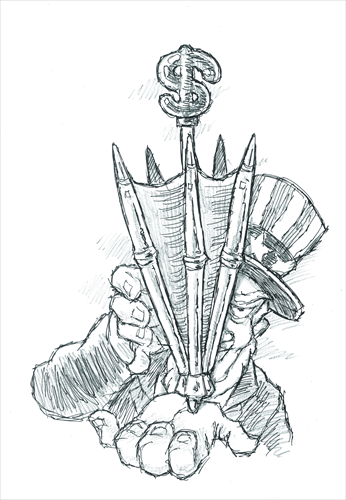

Illustration: Peter C. Espina/GT

A strange phantom game is underway in South Korea. It is a diplomatic game based on proposals to introduce the Terminal High Altitude Air Defense (THAAD) system into South Korea. Expressing concern over how unpredictable North Korean leader Kim Jong-un is, US Secretary of State John Kerry, visiting an American military base in Seoul on May 19, said that is "why we're talking about THAAD." On the following day, US Assistant Secretary of State for Arms Control, Verification and Compliance Frank Rose went further by saying that the US is considering permanently stationing a THAAD missile defense unit in South Korea to help defend against North Korean threats. Such remarks contradicted Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Daniel Russell, who said THAAD is nothing but a "theoretical" issue of a "not-yet-deployed" nature during a recent visit to Seoul before Kerry's trip.

South Korea has exhibited an equally confusing attitude. Up until early 2014, the government denied the possibility that THAAD would be deployed, while maintaining its commitment to a South Korean version of a missile defense. Yet, the country's new defense minister, Han Min-goo, complicated the situation by emphasizing the virtue of "strategic ambiguity" last year. His views were tantamount to implying "yes to the US, no to China." As the public became confused, presidential spokesman Min Kyung-wook sought to calm the situation by announcing on March 11 that "there had been no request, and hence no consultation and no decision."

Yet less than a week later, responding to China's explicit concerns, Ministry of National Defense spokesman Kim Min-seok said, "If the US government raises the issue, we will make our own decision based on military utility and national security interests." That was seen as a willingness to accept the deployment of THAAD if the US requests it. Seoul's position has evolved along a spectrum of "denial-tactical ambiguity-denial-partial approval," fueling the THAAD confusion and controversy.

The fiasco does not stop there.

Originally, Seoul understood that the US would deploy the system to protect the Pyeongtaek US military base. Because South Korea has shown a strong preference over its deployment, however, the possibility of Seoul's purchasing the missile defense system has emerged. Because the public was critical of it, the South Korean defense ministry again announced that it had no plan to purchase it. Such an indecisive attitude was behind the amplification of perceptions of the phantom game.

Does South Korea need THAAD? Its introduction would definitely add to its deterrence capability against North Korea's nuclear and missile threats. It would also allow South Korea to be part of a US-Japan-ROK theater missile defense system, easing public fears.

But serious doubts about its technical capabilities have been raised. At present, North Korea has more than 1,000 short-range (Scud) and mid-range (Nodong) missiles, and it cannot be an effective shield if the North launches decoy missiles with conventional warheads.

More critically, given that it would only take three-and-a-half minutes for a Scud or Nodong missile to reach Seoul, detecting and intercepting the North's incoming missiles might be technically impossible. Price also matters. The cost of one THAAD battery ranges from $1.5 billion to $2.5 billion.

Its introduction could also be counterproductive to national security interests. More immediate threats come from long-range artillery and multiple rocket launchers deployed along the border that threaten the Seoul and Gyeonggi metropolitan areas. Investing massive amounts in THAAD could create trade-off effects in this area of conventional forces.

More importantly, it can only protect public lives and property indirectly, since the system is for the protection of military and industrial facilities.

In addition, its introduction could entail numerous negative consequences: an inter-Korean arms race, Pyongyang's justification of nuclear weapons, and heightened tension on the Korean Peninsula.

China's opposition cannot be taken lightly, either. Beijing sees its deployment as a serious threat to its national security, not only because of X-band radar, part of the THAAD system that can allegedly enable intrusive surveillance over Chinese territory, but also because of its synchronization into the US-led regional theater missile defense.

It might not be easy for Seoul to overcome these hurdles. For South Korea, the best choice is to eliminate or minimize the North's nuclear and missile threat through preventive diplomacy. Should such diplomatic measures fail, the focus should be on strengthening deterrence by securing offensive assets.

THAAD, designed to intercept incoming enemy missiles in their terminal stage, should be considered after these steps are exhausted. Treating defensive THAAD as if it were a panacea is nothing more than misleading the South Korean people. Both South Korea and the US should end the double talk and come clean on the real choices and their consequences.

The author is a professor of political science, Yonsei University, Seoul. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn

Posted in: Viewpoint