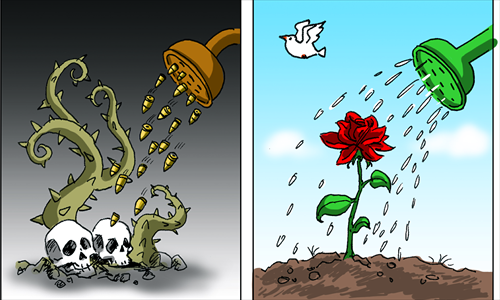

Engagement key to building better world

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

Some realist international relations scholars like to talk about the "Thucydides trap." This term refers to the notion that an emerging power (such as China) will inevitably challenge a global hegemon (such as the US), resulting in military confrontation.

They believe there is no way to avoid this "trap." According to them, peaceful coexistence is impossible. Like boxers in the ring, challengers always have to fight reigning champions to seize the prize of the global throne.

On the other hand, there are those who argue that the Thucydides trap is a self-fulfilling prophecy rather than a real testable theory. The belief that falling into the "trap" is unavoidable leads one toward it like a lemming heading hypnotized over a cliff, rather than seeing the full range of other possibilities.

Besides, say these alternative theorists, there is one clear example of a case when a state took over as a global superpower from its predecessor without armed struggle. That is exactly what happened after WWII when the US replaced Great Britain. So this suggests that the "trap" is merely a mental construct, an intellectual prison into which thinkers influenced by the Machiavellian philosophy of cynical realpolitik lock themselves.

So we find some Western powers rejecting engagement at certain points in time with so-called rogue states of the last two decades such as Iran, North Korea or Zimbabwe. Their claim is that these nations' rulers are so abhorrent that it is better to place economic sanctions on them and to refuse to have anything to do with them.

Such pariah states ought to be shunned, goes the argument. Even when contact is later re-established, it seems to come with an implicit frown of disapproval, as if the whole country and its people are permanently tarred with the stain of not having toed the line quickly or fully enough.

There are two major logical problems with the disengagement approach to international affairs. The first is that it is difficult to have a positive impact on another country's development if one is not actively engaged with it. Standing back and saying "No! Not good enough!" does not constitute constructive action. In fact, it is more reminiscent of abstention from, or avoidance of, action.

The second problem is that by punishing a nation that does not conform to one's expectations, one is punishing not only the leaders who decided the policies that are disliked, but also all the people who live in that country, however innocent they might be. In fact, one is probably punishing the citizens far more than their rulers, since the rulers have first access to whatever resources come the country's way, and have the power to deny a share to their people.

So this second problem is, in a way, more serious. When countries refuse to engage with a "rogue" nation and apply sanctions to it, they are actually negatively affecting the lives of millions of individuals. For instance, if they refuse to supply food or resources, it is the ordinary citizens of the state who will suffer most, not the leaders.

Such disengagement also does little to enhance the soft power or status of the snubbing state within the snubbed nation. How are the people of the sanctioned state to learn about the norms and values of their supposed betters if they are not permitted to interact with them?

Disengagement is thus not really an effective policy. It does not reform the "rogue" state, but merely tends to embitter it.

On Chinese President Xi Jinping's recent visit to Britain, British Prime Minister David Cameron was accused in many quarters of "sucking up" to the Chinese president. The implication was that it would have been better to stay disengaged from China than to endorse its government.Yet it is only by engaging with those with whom we do not necessarily see eye to eye that we can hope to build better relations in the long term. And this applies as much to China as it does to the Western powers.

China also may not agree with aspects of the British or American way of doing things, nor with British and American foreign policy in many parts of the world, but that does not mean that it will disengage from the Anglo-Saxon powers. This is because the Chinese government understands what its critics in the West apparently do not: that in the attempt to build a better world it is always better to engage with other nations, however much their values may differ from one's own, than to fall into the trap of disengagement.

The author is lecturer in International Relations, Jan Masaryk Centre for International Studies, University of Economics in Prague. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn