HOME >> OP-ED

China’s meritocracy rooted in political values

Source:Global Times Published: 2016-1-13 0:08:01

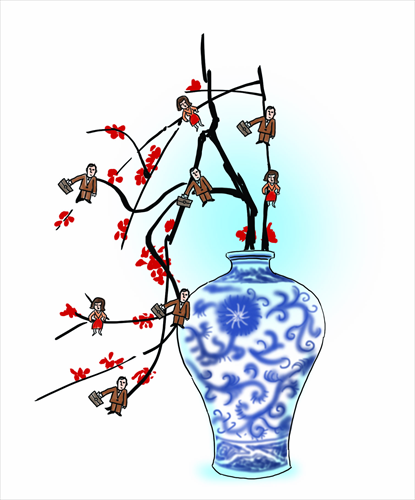

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

The most striking cultural shifts in China over the last two decades or so has been the revival, both orchestrated and spontaneous, of tradition. The main trope for culture in the twentieth century, especially since 1949, has been anti-traditionalism. As far back as the May 4th movement in 1919, and before, whether it was the financial elite, the liberals, the Marxists, or anarchists they all agreed that China was poor and that one of the causes of that state of affairs was the backward traditional culture.

We have witnessed a dramatic reevaluation of tradition in China, and also in other East Asian countries with a Confucian heritage such as Korea. This part of the world has witnessed rapid growth over the last three decades that has sharply reduced poverty and the region has remained at peace. So when people look around and ask what do all these countries have in common, one answer is their Confucian heritage. So whereas the previous narrative was that Confucianism undermined modernization and economic growth, now many argue that it actually helps.

We are witnessing the return of a more historical and humanistic perspective on the world, an emphasis on education, a concern for family across several generations, and a new assessment of the value of China's tradition of political meritocracy. Chinese have long held that the key to a political system is the selection and promotion of leaders with superior abilities, ethical qualities and social and cultural skills who can best lead the nation forward.

The perspective has Confucian roots, but it has been modernized and has been the core of the strategy for economic development in China and other East Asian countries such as Korea and Japan. Although Confucian ideology was denounced during the Cultural Revolution, it is taking on a new centrality today. And the promotion of core Confucian values is not limited to the government. We see similar efforts in business and in the non-profit sector.

At the end of the day, my view that there is no one standard for evaluating political progress or regress that is universally applicable. There's different reasonable ways approaching the question of what is a good political society. From Plato on we have seen competing models for society, and for utopia. The American standard for measuring political progress and reform in accordance with the democratic ideals embedded in its Constitution and advocated by its founding fathers have had great impact on many political movements in American history. Of course, there is always a huge gap between the ideal and the reality.

But at the end of the day, the standard for evaluating reality should draw on the leading political ideas embedded in US civil culture.

The same holds for China which has its own complex history of political philosophy and its own ideals. We can trace those ideals back to debates carried out throughout Chinese history, from Confucius and Mencius, over political meritocracy. Chinese thinkers gave much thought to how to select able and virtuous political leaders, which abilities matter and which virtues matter? Chinese pondered about, and experimented with, mechanisms for selecting leaders. And that tradition continues today. Over the last thirty years in China, the political leadership has been selected first and foremost through examinations, followed by evaluations of performance at lower levels of government. No one rises to the top without extensive experience at all levels. And that approach is quite similar in form to what we have seen throughout much of China's imperial history.

I do think that the central political ideas articulated in Chinese culture ought to serve as the standard for evaluating political progress or regress in China. And I do think those values are different from the liberal ideas embraced in the US. There is a huge gap between the ideal and the reality-that is always the case. But the more fundamental question is: what should serve as the standard?

It's an issue for the Chinese government and intellectuals. Whether they like it or not, what China does "shakes the world" and China must take a more active role in shaping the world. The question is whether it can play this role in way that promotes international peace while allowing for difference. Most Chinese recognize that the world's powers will have different forms of government and we should refrain from pushing any one form of governance.

The article was compiled by Emanuel Pastreich, an associate professor at Kyung Hee University, based on an interview with Daniel A. Bell, Chair Professor of the Schwarzman Scholar Program at Tsinghua University. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn

Posted in: Viewpoint