Women’s Day should be about hard work, not pretty pictures

Illustration: Shen Lan/GT

The original name of Women's Day was International Working Women's Day, but you wouldn't know that from watching Chinese media. An endless parade of beauties were brought out to mark March 8th, dressed in delicate finery. Modelling is hard, exploitative work, true, but work seemed the furthest thing from anybody's mind at these events.

Women's Day is a socialist festival, one pre-dating any Communist country but that exemplifies the spirit of late Chinese leader Mao Zedong's often-repeated statement that "women hold up half the sky." In my experience in China, I'd say we owe about 80 percent of the horizon to women; most places I've been they do most of the work and the men take most of the credit.

International Working Women's Day was originally an activist celebration, one that was meant to draw attention to the work women did and their demands to be treated fairly for it. Socialist posters showed women getting their hands dirty, outperforming men, competing and fighting for their own rights. It wasn't about looking pretty or being pampered; it was about working hard and being treated fairly.

But somewhere along the way, the wires seem to have got crossed. In China, women's day seems to have become little more than wallowing in exactly the stereotypes of femininity that the event was founded to challenge. Stages are swathed in pink and roses.

Women's "beauty" and "charm" is praised. Male students hang out slogans asking for dates from their female colleagues that say "You would make good wives." Instead of celebrating women's work and challenging patriarchy, official groups put on fashion shows and the media posts picture galleries of "the most charming" women at events. Weibo encourages men to "pamper" women and tells them to "find love and indulgence together."

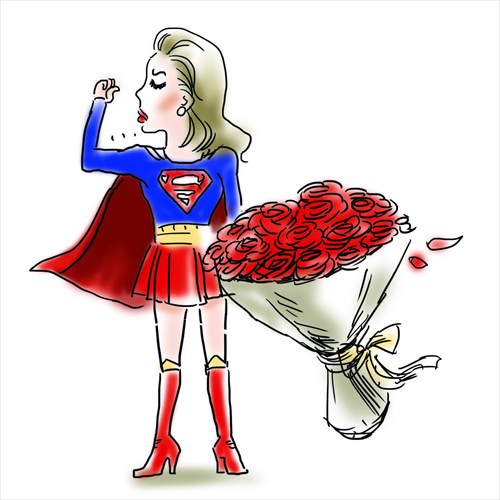

This is a long way from the images of empowered, strong women that the day was built on. Look at the Soviet posters showing women in the factories, or the US WWII images of "Rosie the Riveter" with arm bent and muscles showing. Then check out the dainty images put out by Chinese brands looking to exploit the day.

Part of the reason for this focus on fashion is historical. In early 20th century China, modernity and femininity were often wrapped up for Chinese women. The image of the city woman, glamorous, independent, and stylish, was a powerfully appealing one - both for activists and for advertisers. Even after the foundation of the People's Republic of China, these images were carried over in both advertising and political propaganda; women might be shown working in the fields or the factories, but they would look good doing so.

In the early 1980s, too, cosmetics and fashion were aspirational items for women after the darkness of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76). Red Guards had imposed an image of aggressive plainness, all buck teeth and pigtails, and attacked women using make-up or wearing "foreign" clothes, and so the chance to be beautiful was a form of defiance in itself.

But the real motive may be that images of beautiful women are a lot easier for companies to exploit than empowered women. Why let your female workers unionize, or close the pay gap with men, when you can give them chocolate and roses instead? The second is a lot less threatening to the men in charge than the first. Why worry about their underrepresentation in parliaments when you can put a parade of models on stage?

Women's Day was once about getting tough and working together. Now it's a smudgy Valentine's Day, a hazy cover over the persistent sexism and discrimination that still holds back women across the world. Don't get roses, women. Get angry.

The author is an editor with the Global Times. jamespalmer@globaltimes.com.cn